Hidden Fees Highlighted by Hidden Researchers: A Citizen Science Approach to Detect Overcharging in Digital Financial Services

The term “citizen science” describes a unique way to conduct research: it uses members of the general public to help researchers collect data rather than relying on professional enumerators for data collection. Citizen science has been put to use across a wide range of disciplines, from collecting COVID-19 symptoms to scanning images of space captured by telescopes. Now, in an IPA-managed study, citizen science has been deployed to investigate a common concern among digital financial service (DFS) users —overcharging by mobile money agents. We used citizen science volunteers in Bangladesh and Uganda to measure the extent mobile money agents add on unofficial fees to services, also known as agent overcharging.

DFS usage has drastically increased over the past few years, as 76 percent of adults globally now have a bank or mobile account, up from just 51 percent in 2011 (World Bank, 2022). As DFS usage increases, so do risks to consumers. IPA’s Transaction Cost Index found that 19 percent of DFS transactions in Uganda and 7 percent in Bangladesh were subject to overcharging. IPA surveys in both countries also found that overcharging was one of the most common challenges consumers face. These risks can undermine the delivery of financial services to low-income consumers, diminish users’ trust in DFS, and hurt financial inclusion efforts.

Our Approach

To test a citizen science approach, we partnered with local organizations to recruit consumers to be citizen scientists: Youth Policy Forum in Bangladesh and the Network for Active Citizens in Uganda.

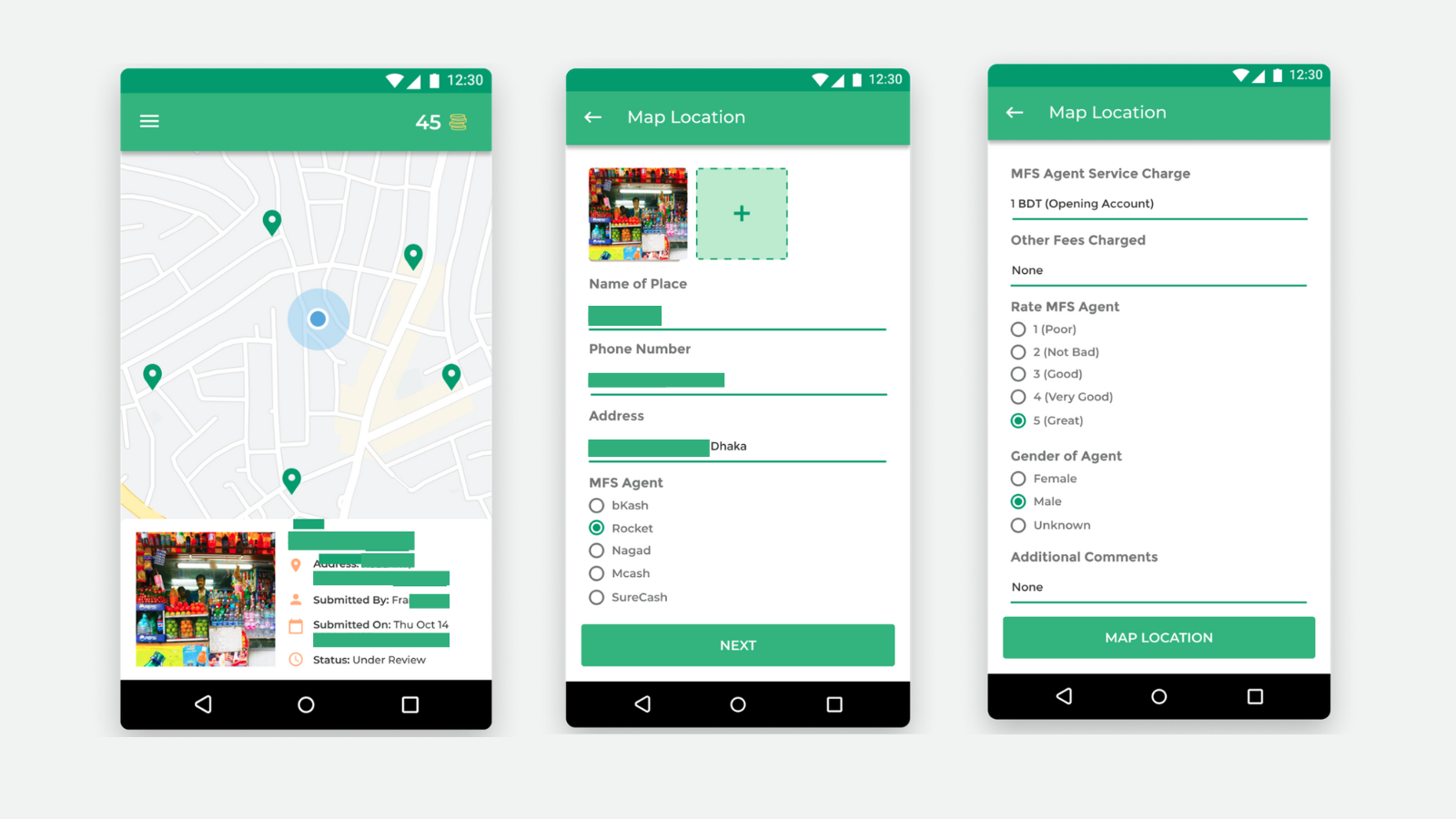

We trained these volunteers to use a smartphone application, POKET, to register DFS agents and record their experiences when making DFS transactions in real-time. The volunteers could also survey people who just conducted a transaction, or people they know, about their experience conducting transactions. To validate the data collected by volunteers, we also conducted professional mystery shopping, where trained enumerators replicate typical customer interactions with mobile money agents, like depositing funds into accounts, and record exactly what happened.

What Did We Find?

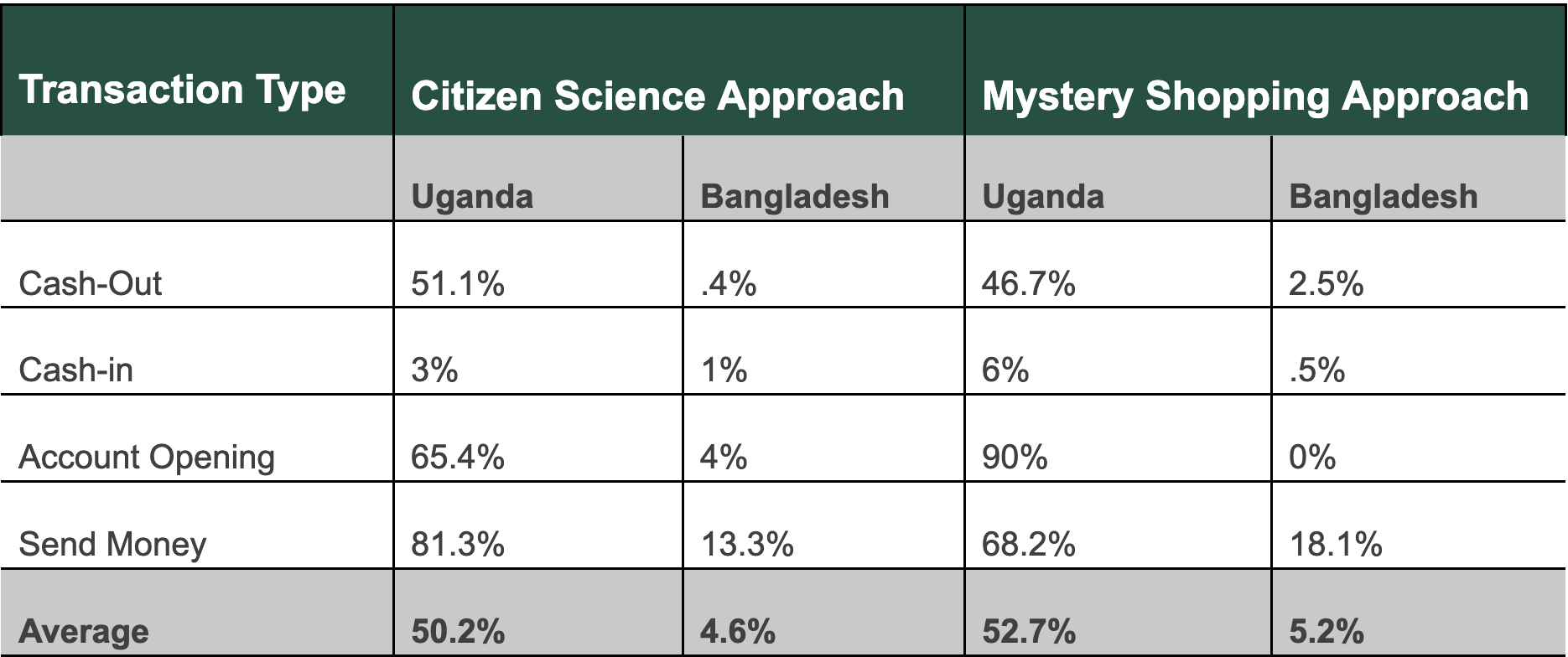

Table 1: Overcharging Rates by Country, Method, & Transaction Type

Overcharging is dramatically more common in Uganda than in Bangladesh. Across all transaction types we evaluated, overcharging was much more common in Uganda than in Bangladesh. This is true for both citizen scientists and professional mystery shoppers. For instance, the average rate of overcharging for citizen scientists in Uganda was around 50 percent, while the average in Bangladesh was around 5 percent. The rates were similar for professional mystery shoppers; around 53 percent in Uganda and around 5 percent in Bangladesh.

Sending money and account opening have very high rates of overcharging. Typically customers open accounts on their own, but some agents can provide informal support. Sending money and account opening services typically don't earn agents formal commissions, but they do have an associated cost for consumers. So it makes sense that agents would charge a fee to try to earn some compensation for their services.

Withdrawals are also much more likely to be overcharged than deposits. This is likely because deposits are nominally free and withdrawals aren’t. Therefore, it’s easier (and less suspicious) for agents to overcharge customers on a service that has a fee versus one that’s free.

Challenges

Citizen science may be an effective way to better understand and highlight consumer risks, but we should continue to evaluate how we can improve this research method. Throughout this study, we identified a few challenges to effectively using citizen science in consumer protection research.

- Data quality: It’s possible that citizen scientists may not collect reliable data. While this is a concerning issue, we found a way to overcome this. In addition to the professional mystery shopping, we also conducted rigorous data checks and identified red flags during the piloting period. These flags include implausible transaction amounts or data submissions outside normal business hours.

- Engaging volunteers: While we used financial incentives during these pilots to engage volunteers, future citizen science studies should explore how similar projects utilize novel engagement techniques, such as posting study updates to a public forum. Utilizing non-monetary engagement mechanisms also makes this a more affordable way to conduct data collection.

- Training volunteers: To facilitate data collection, we trained the citizen scientists to input their data. On a larger scale, it would be quite expensive to continuously train new people. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to integrate training into the data collection platform and develop a public forum where participants can ask and answer questions.

As fraud tactics and consumer risks continue to evolve, it’s important that our research methods evolve as well. We must continue to push the boundaries of consumer protection research by testing new and innovative solutions like citizen science.