Why We Are Building A Humanitarian and Forced Displacement Initiative

Hakimpara refugee camp in Bangladesh. Photo: Jared Kalow

The world now has over 70 million forcibly displaced people. This is the highest absolute number in history, and the proportion of displaced people has risen by a dramatic 48 percent in recent years—from about 1 in every 160 people in 2009 to 1 in every 108 people today, according to UN data. Yet there is very little evidence on what works for forcibly displaced and host community populations. IPA is responding to this gap by launching a new Humanitarian and Forced Displacement Initiative, under the academic leadership of Dr. Jeannie Annan and Dr. Mushfiq Mobarak.

The growing trend of forced displacement is the result of both increased displacement within countries and from one country to another, due to conflict and climate change. These humanitarian crises are increasingly protracted, with many displaced spending over half a decade in limbo, unable to return home and without a country to take them in. The number of individuals forcibly displaced is expected to continue to rise in the coming years.

The crisis has attracted attention from global leaders. This week ministers from around the world will meet for the first-ever Global Refugee Forum, which is organized as part of the Global Refugee Compact, affirmed by the UN General Assembly in 2018. The Compact makes an explicit commitment to create “reliable, comparable, and timely data [which] is critical for evidence-based measures” to improve humanitarian programming, find solutions to humanitarian crises, and assess the impact of these crises. IPA has pledged to contribute to this movement with the new Humanitarian and Forced Displacement Initiative.

Yet generating evidence on what works in humanitarian and forced displacement settings is easier said than done. Evidence from humanitarian settings is thin and (aside from the use of cash) evidence-based solutions on the ground have been hard to come by. How can the forcibly displaced best be integrated, both socially and economically, so that the displaced and their host communities both benefit? How should services such as education and health be delivered for dynamic populations in challenging settings such as refugee camps and informal settlements? How can humanitarian responders best meet the psychological needs of the displaced? How can organizations both prevent and respond to harm in humanitarian crises?

Answering these questions is important for two reasons. First, without evidence, even the most experienced policymakers and practitioners are delivering best-guess policies and programs. Our experience at IPA shows us that when we evaluate impact, we often find different results than what practitioners and decision-makers expected. Programs can be more or less effective than expected or have an impact on different outcomes than initially planned—and sometimes, otherwise helpful programs can have unanticipated negative side effects.

Second, the arrival of refugees, especially in large numbers, is often interpreted by citizens as a threat to their livelihoods or social fabric. Citizen concerns around potential impact on wages, costs, and even cultural norms sometimes lead host country leaders to deny refugees rights such as free movement and the right to work. Creating robust data on the impact of refugee crises can help both citizens and leaders develop their opinions and policies based on facts and not feelings.

We estimate that there are more panel surveys and rigorous trials in the field right now than have ever been published related to humanitarian practice and forced displacement.

In the past two years, IPA has responded to the call for more evidence on forced displacement and in humanitarian settings through the Peace and Recovery Program, part of the DFID-funded J-PAL/IPA Governance, Crime and Conflict Initiative, as well as through research opportunities in our Social Protection and Education programs. You can read about all of the projects we’re funding through the Peace and Recovery Program here.

Although IPA is often associated with randomized controlled trials, we recognize that not every problem needs an RCT. Often even descriptive data can help us understand where to direct resources and inform better policy.

With support from USAID's Office of Food for Peace, IPA has been given the opportunity to translate knowledge of what works from development settings to humanitarian contexts, by evaluating AVSI and Trickle Up's application of the Graduation Approach for refugee and host communities living in Western Uganda. The evidence base on the Graduation Approach is strong with studies from more than six countries showing positive impacts on a wide range of outcomes after three years. However, while this approach is now being scaled in many development contexts, its effectiveness for humanitarian environments is still not known. (At the Global Refugee Forum this week we will be participating in a Spotlight Session with other members of the Poverty Action Coalition on Alleviating Extreme Poverty that will be transmitted live (more info here) where you can learn more.)

Although IPA is often associated with randomized controlled trials, we recognize that not every problem needs an RCT. Often even descriptive data can help us understand where to direct resources and inform better policy, but right now there’s a dearth of good data on most refugee crises around the world.

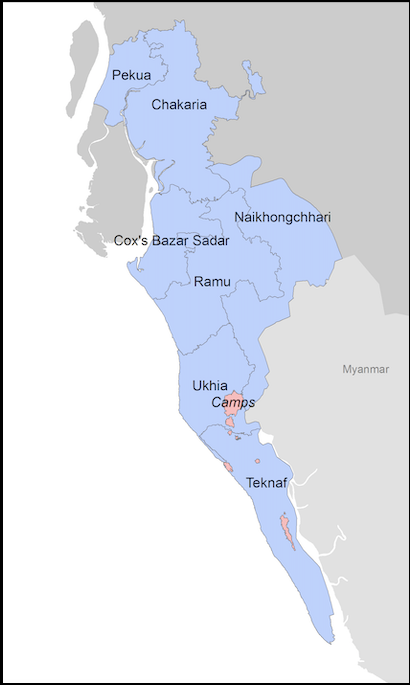

In 2017-2018, 745,000 Rohingya people fled violence in Myanmar’s Rakhine State and arrived in Bangladesh. Most of these people now live in densely-populated refugee settlements in Bangladesh’s coastal Cox’s Bazar district. (The map at left shows the location of refugee camps in Cox's Bazar District.) IPA has been working with researchers Austin Davis, Paula López-Peña, and Mushfiq Mobarak to track refugees with a representative survey of more than 5,000 households, equally divided between Rohingya refugees and Bangladeshi host communities. In Bangladesh earlier this month, IPA co-hosted an event with the International Growth Centre to launch the findings of the survey’s first wave. In a room with over 90 policymakers and practitioners involved in the humanitarian response in Bangladesh, the researchers demonstrated with numbers that the Rohingya were not all that different than the Bangladeshis living in Cox’s Bazar before they were displaced. They had similar assets such as homes, poultry, and cell phones, and worked in similar agricultural activities where they were just as productive. We will run this panel survey yearly in order to track how indicators change among both refugees and host community members, and will continue to work with practitioners and policymakers to determine what interventions should be prioritized for testing to support the needs of both populations.

The Rohingya were not all that different than the Bangladeshis living in Cox’s Bazar before they were displaced.

We are also building new partnerships to explore questions that have the potential to impact millions of people living in crisis. One example of this is our work with the IRC and several other organizations to support education and care of refugee children living in East Africa and Bangladesh. With over 31 million refugee children displaced globally, many kids will spend their formative years in these settings. Scientists, practitioners and policy makers don’t yet know what kinds of interventions can best support children's development in contexts where children have been exposed to trauma, stunted physical development, and severe emotional challenges. IPA is grateful to be working with research, media, and practitioner partners, and with funding from the LEGO Foundation, to try to develop better solutions for children in these situations.

We will continue responding to the urgent need for evidence related to forced displacement, especially in humanitarian settings, and are grateful to our funders, partners, colleagues, and the participants in our studies for allowing us to do our part to contribute to evidence-informed decision-making. We are excited to attract and support researchers who are interested in tackling these issues. Thanks to the combined efforts of all these actors, we estimate that there are more panel surveys and rigorous trials in the field right now than have ever been published related to humanitarian practice and forced displacement. In the coming years we will have a lot more evidence to share—and we look forward to adding to the decision-makers’ and practitioners’ toolkit as they respond to one of the most urgent issues of our time.