The Ultra Poor Graduation Approach

Abstract

The proven success of the Graduation Approach has spurred governments and development agencies to expand the model to millions of people.

Evidence from six countries found that a “big push” program, which aimed to address the many challenges of poverty simultaneously, boosted livelihoods, income, and health among the ultra-poor. The proven success of the approach has spurred governments and development agencies to expand the Graduation Approach to millions of people. The program is now being scaled up to reach over 3.1 million households worldwide. In addition, a new initiative plans to scale-up the Graduation Approach to reach half a million refugee- and host-community families in 35 countries over five years.

The Challenge

More than 700 million people live on less than US$1.90 a day (PPP), and the there is an international agenda to drive this share to zero by 2030.[1] Reaching this objective will mean enabling the poorest families, who are often the most marginalized within their communities, to shift from insecure and fragile sources of income to more sustainable ways of earning a living. One possible avenue, popular with both development organizations and governments, is to promote self-employment activities such as animal rearing or petty trading. But is it possible to reliably improve the livelihoods of the poorest households by giving them access to self-employment activities? And is it possible to come up with a model for doing so that can be implemented by a wide variety of organizations and works in a wide range of geographic, institutional, and cultural contexts?

The Evidence

Evidence from a six-country study released in 2015 found that a “big push” intervention that aimed to address the many challenges of poverty simultaneously, boosted livelihoods, income, and health among the ultra-poor. The centerpiece of the program was providing households with an asset to spur self-employment.

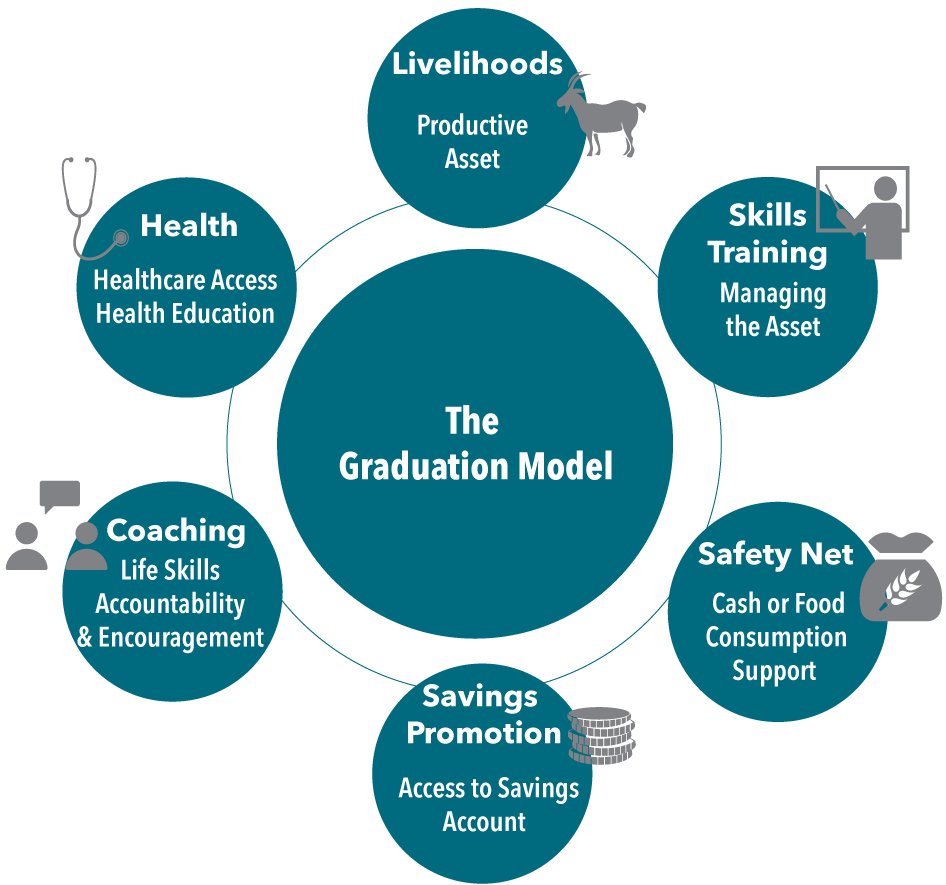

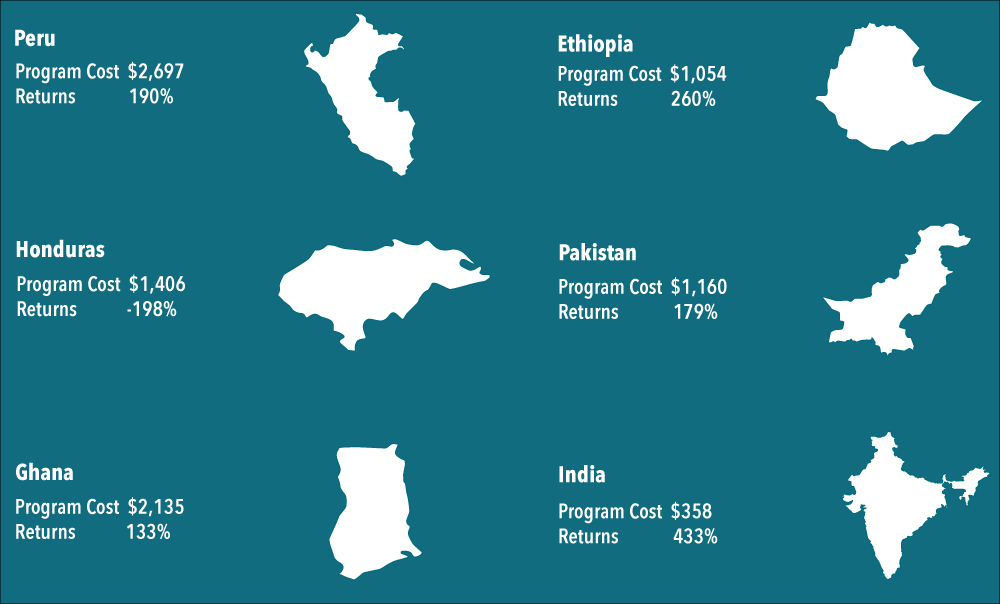

The randomized evaluations followed 21,000 people in Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, India, Pakistan, and Peru over three years. Researchers wanted to find out not only if the program worked in one setting, but if the effects were similar in multiple settings. Households randomly assigned to participate in the program received multiple types of support at once:

- An asset to spur income generation, such as livestock or goods to start an informal store.

- Training on how to manage the asset.

- Basic food or cash support to stabilize households and reduce the need to sell the new asset in an emergency.

- Frequent (usually weekly) coaching visits to reinforce skills, build confidence, and help participants handle any challenges.

- Health education or access to healthcare to stay healthy and able to work.

- A savings account to help people put away money to invest or use in a future emergency.

One year after the program ended—three years after receiving the assets—program participants on average had significantly more assets and savings, spent more time working, went hungry on fewer days, and experienced lower levels of stress and improved physical health compared to those who did not receive the program. The program was also cost effective, with positive returns in five of six countries, ranging from 133 percent in Ghana to 433 percent in India. In other words, for every dollar spent on the program in India, ultra-poor households had $4.33 in long-term benefits.

The Impact

Given the proven success of the approach, governments and development agencies have launched efforts to expand the Graduation approach to millions of people in 35 countries. In India, three state governments are expanding the approach, including a plan and funding to reach 100,000 households in the state of Bihar.

Also, a new initiative plans to scale-up the Graduation Approach to reach half a million refugee and host-community households in 35 countries over five years, from 2020 to 2025.

In addition to these scale-ups, USAID reported to Congress in 2018 that it is shifting away from traditional microfinance and moving toward other approaches for poverty alleviation in response to the latest evidence. The report cites IPA evaluations of the Graduation approach, microcredit, and savings products and concludes:

"Based on the evidence we have gathered thus far on microenterprise and microfinance, USAID is shifting our approach to include interventions that address multiple challenges simultaneously, such as using the Graduation Approach and building inclusive market systems. USAID is confident that greater impacts on poverty alleviation can occur by expanding the focus from only microenterprises to including MSMEs, enabling and leveraging market forces to the greatest extent possible, and reducing regulatory burdens, to create sustainable pathways out of poverty for the poor and very poor." Read the full report.

IPA also helped design and is overseeing evaluations of the Adaptive Social Protection Program in the Sahel (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal). The program, which aims to increase access to effective social protection systems in the region, while also helping the poor and vulnerable adapt to climate-induced changes, was designed in part based on the Graduation Approach.

If you know of other organizations that are using these results, or have any corrections or updates to make to this case study, please contact comms@poverty-action.org.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Sources

1 http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/poverty/