Does Self-Perception Affect Consumers’ Willingness to Seek Redress?

In the 1980s, economist Amartya Sen posited his capabilities approach to understanding human development and welfare. Sen emphasized that increasing welfare requires not only providing access to resources (like education, healthcare, and financial services), but also ensuring individuals have the confidence, agency, and capability to make their own decisions about how (if at all) to use those resources.

In the context of financial inclusion, a capabilities approach would ensure that financial services are not only made available to all, but that individuals have the social, economic, and psychological means to use these services, raise complaints (often called grievance redressal), and resolve disputes. In India, we set out to test this dynamic: whether people’s beliefs about their agency influenced their attitudes toward digital financial services (DFS). While digital platforms have brought more people into the formal financial market, the welfare impact of financial services also relies on people’s ability to navigate the financial system, belief that the system is fair, and willingness to seek redressal.

In 2022, we conducted a survey in rural areas of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in India to examine this very dynamic — could internal factors like perceived agency drive differences in consumers’ willingness to seek redress? We asked: would women be less likely than men to try to fix a problem in a digital transaction because they believe they have less control over their lives? We also examined how external factors like social norms could affect redressal behavior by posing the question: would women be less likely than men to try to fix a problem because of norms that women who attempt to solve digital finance-related problems should fear retribution?

Along with our colleague Pavan Mamidi, we asked women who already use digital financial services through smartphones how they behave when something goes wrong with a transaction. In total we asked 13 interviewees qualitative questions and conducted a survey in which 230 women responded. We specifically asked questions to understand if the following concepts impacted women’s decisions to seek grievance redressal differently than men:

- Locus of control: beliefs about what controls the course of one's life – either primarily one's own thoughts and actions (known as internal locus of control) or external circumstances (external locus of control) (Rotter 1966). Someone with an external locus of control could easily assume that it wouldn’t be worth resolving an issue if their bad luck created the problem in the first place.

- Self-efficacy: belief in our ability to meet the challenges ahead of us and complete a task (Bandura 1977). Greater self-efficacy should correspond with a higher likelihood of pursuing grievance redressal.

- Fatalism: the belief that human lives are predestined and not influenced by individual actions. A highly fatalistic person might believe that having a DFS problem is their destiny and can’t be resolved.

Here’s what we found:

Out of the three factors, men and women only differed regarding the locus of control. While women and men answered similarly regarding self-efficacy and fatalism, female respondents reported significantly lower internal locus of control than men. In other words, women feel they have less control over their lives than men. We also observed that a lower internal locus of control is not necessarily associated with lower self-efficacy, as people believe that destiny favors those who work hard.

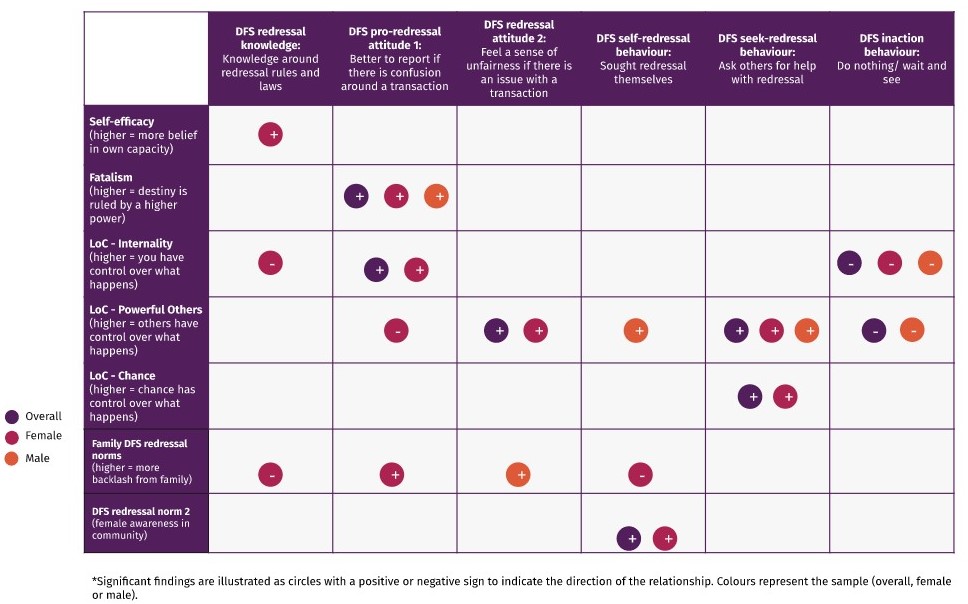

Figure 1: Predictors of Grievance Redressal - Women have less knowledge of how to resolve DFS complaints, but that didn’t impact their trust in DFS. Knowledge of DFS redressal mechanisms among our respondents was generally low, but women scored significantly lower than men. The mean score for women was 2.54 out of 4; for men, it was 2.7 out of 4. Despite this lack of knowledge, there was no difference in trust in DFS between women and men. This may be due to the fact that we only surveyed people who already use finance apps.

- Women and men feel the same about reporting DFS issues. Men in our sample reported a higher perceived norm that their community respects people for seeking redress. Despite this, women and men have similar attitudes in favor of reporting issues they faced while using DFS (80% and 79%, respectively). They also equally feel a sense of unfairness if they encounter problems. While reports of handling past problems on one’s own were similar between men and women, women were significantly more likely than men to ask their family or friends to help solve their DFS-related problems (women sought redressal through family/friends for 39% of their DFS-related problems, while men did this for 32% of their problems).

- Household and community norms of retribution for making mistakes influence women’s likelihood of seeking redressal on their own. Women in our sample who reported a higher perceived norm of receiving family backlash for experiencing DFS-related issues were less likely to seek redressal on their own. Conversely, women who reported a higher awareness of DFS among women in their community were more likely to seek redressal on their own, indicating that perceived norms drive differences in behavior.

- There’s no significant correlation between the three psychological traits and an individual’s likelihood of seeking redressal on their own. However, our analysis found that locus of control strongly influenced the sample’s likelihood of preferring to ask others for help and doing nothing in response to problems (over seeking redressal independently). Particularly among women, those who reported the belief that other individuals and chance influence the course of their life were more likely to ask others for help with their problems. Conversely, women with a higher internal locus of control were less likely to be inactive in response to their problems.

Our data uncover far more similarities than differences by gender among existing DFS users. This finding surprised us, but hindsight provides two plausible explanations. An existing field of research is investigating if technology empowers women, meaning internet access could have increased women’s agency in line with men’s (Pazarbasioglu et al 2020; Field et al 2021). Perhaps, a more plausible explanation for rural Uttar Pradesh and Bihar is that only women with high agency could access smartphones and use DFS, and therefore be part of this research. In this case, service providers and regulators as well as researchers should be aware that women who already use DFS are unlikely to represent all women. For example, women who are not as confident as these early adopters may need specific assistance to prevent and solve problems when they arise.

As a result, the next question we need to answer is whether agency and confidence prevent women from even using digital financial services in the first place, and if they do, find ways to increase these internal motivators of behavior. To make sure formal financial services yield the biggest impact, researchers need to better understand how women’s agency and locus of control can help or hinder the efficacy of financial products.

This study was funded by Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA)’s Consumer Protection Research Initiative.

Cover Photo by Charanjeet Dhiman on Unsplash