Using Mobile Platforms to Save for the Future: Evidence from Kenya

Co-written with Alejandra Martinez

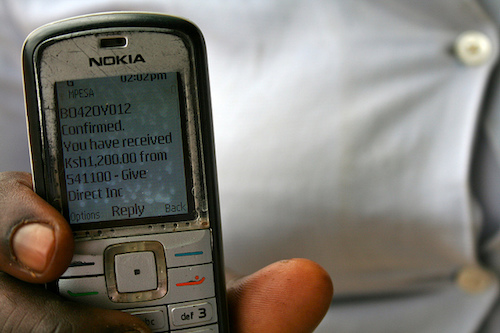

In this post, we feature an interview with James Habyarimana, Associate Professor at the McCourt School of Public Policy, and William Jack, Vice Provost of Research and Director of gui2de, both at Georgetown University. They conducted a field experiment in Kenya to test whether access to a mobile bank account or a restricted, goal-based account (i.e commitment savings account – which encouraged users to hold onto the money until school expenses were due) could help parents save for their children’s education expenses. Here, they both share their thoughts on the importance of credibility of financial institutions for the take-up and usage of savings products, the benefits of having a mobile bank account and highlight the benefits of leveraging existing mobile platforms like M-PESA to market and increase take-up of new products.

Alejandra: You look at the impact of mobile banking accounts and commitment savings accounts on parents’ savings for their children’s school fees and other costs to attend secondary school. Could you tell me more about why you chose this topic and the purpose of the study?

Billy: The idea was to look at the way that financial inclusion and access to mobile banking services could have an impact on savings behavior in the context of a particular event that might plausibly require the accumulation of financial resources.

Alejandra: Most of the parents in your sample already had an M-PESA account at the beginning of your study, how do you think that influenced the take-up and usage of the savings products?

James: There are several reasons why experience with M-PESA was important for take-up in this intervention. At the very high level, new banking products work best with an actor that already has some credibility and a pretty strong brand. When trying to promote this kind of savings or any other intertemporal product, trust is a very important issue. The fact that the bank (Commercial Bank of Africa) was using this well-established platform with pretty good brand recognition helps people to feel comfortable when trying a new product.

Billy: It comes to, do you have a mobile device? Are you comfortable using a mobile device? Are you comfortable giving your money to an institution?

The mobile banking accounts were branded as “M-Shwari.” Everybody thought M-Shwari was a Safaricom product when in fact it wasn’t; it was a product of the Commercial Bank of Africa. This bank had a very limited client base at the beginning and, within a few years, had 10 million accounts. Everybody thought “I got M-PESA, I trust M-PESA, it works, it´s reliable, they don’t steal my money, it’s easy access and now M-PESA is giving me a bank account, they just called it M-Shwari.” They already had complete trust in this institution that they thought was behind the product, even though it wasn’t like Safari hid the fact that the accounts were from the bank.

Alejandra: Research in the Philippines and Kenya found that commitment savings accounts to help the poor meet their savings goals. You found little additional effect on savings from a commitment account compared to the mobile banking account. What do you think might explain these results?

James: The M-Shwari product had been in the country for a while, even though we introduced a lot of households to it. The commitment accounts were very new. In fact, we were rolling these accounts out literally weeks after they had been introduced nationwide. Given that it was introducing such a strong commitment—put your money in and it stays in for some specific amount of time and there are penalties for withdrawing—trust and experience may be even more important. People may have needed to learn a little bit about the product and learn what other people´s experiences were before they became comfortable with it.

Billy: To use M-Shwari in your phone, you access it through M-PESA and then select it from a menu. However, you can’t access the commitment savings accounts through the platform. You have to remember a code and use a kind of clunky interface to put your money in the account. These aspects might account for the difference in use between these accounts.

Alejandra: Secondary school expenses are usually a well-defined expense in time and quantity. How do mobile banking accounts compare to mobile money for saving for this kind of long-term objective?

James: M-PESA is probably better than under-the-mattress in addressing some of the temptations or the behavioral constraints people face. However, I think there are more labeling opportunities with the mobile banking accounts than with M-PESA. M-PESA is where your money sits: you send money to your mom or you use the money to pay for electricity bills. With a mobile banking account you can say, “This money is for my child’s schooling,” and it is much easier to think about it as a special account for that.

With a mobile banking account you can say, “This money is for my child’s schooling,” and it is much easier to think about it as a special account for that.

Alejandra: How do you think your study builds on existing research?

James: This research demonstrates that mobile accounts like M-PESA that provide banking services at much lower costs can, in fact, be used to get people to achieve important investments especially long-term human capital formation goals. One could argue that the platform provides opportunities to make saving easier for households through mental accounting since a mobile phone allows you to communicate regularly with subjects, sending reminders to save, which didn’t have an effect in this study, but has elsewhere.

Billy: There is a conundrum on why having a bank account is so important when M-PESA provides nearly as much. In general, the question is: how can we design financial products that help people or nudge them to articulate and achieve their goals? Maybe people would reach their aspirations and goals if they had an easier way to achieve them.

In that sense, there are a lot of innovations that you can imagine to improve goal-based savings. Instead of saving for secondary school by putting money in a lock box, you could send the money directly to the school to pre-pay. You still want to be able to retrieve it if it turns out your kid doesn’t end up going to school, but that’s a stronger commitment. It is giving someone else some authority over your decision to make it somewhat difficult for you to change it. This could be done through an app or an option in M-PESA using your school ID. It could be for any semester, not just transitioning to secondary school. Many product innovations could leverage this remarkable platform.

Alejandra Martinez recently graduated with a Master's in International Development Policy from Georgetown University. She is a former intern for the Financial Inclusion program.