Supporting the Most Vulnerable Amid the Risk of Returning to Poverty: What the RECOVR Survey Tells Us about Pandemic Response in Colombia

By swiftly enacting a national lockdown and sticking with it until a slow and partial reopening in June, Colombia has so far been spared the high COVID-19 infection rate and the related death toll of some of its neighbors like Brazil and Peru. While the restrictions to movement and gatherings protected the health system and saved lives, the economic impact of these restrictions has been felt across Colombian households. One in four Colombian workers (roughly 5.5 million people) lost their job in April, with women and those under the age of 30 among the hardest hit, and by May the unemployment rate exceeded 20%, the highest in more than 20 years.

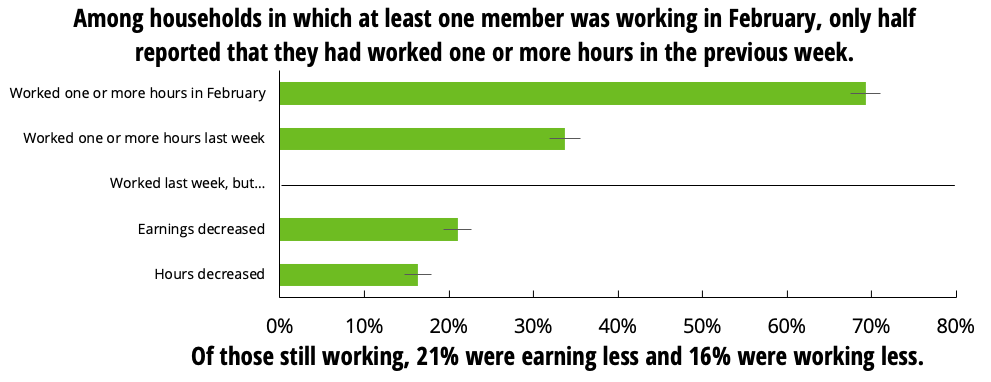

In May, IPA ran a nationwide RECOVR Survey of 1,500 households in partnership with Colombia’s National Planning Department (DNP), the agency within the national government in charge of defining and recommending public policy, to support the Colombian government in making decisions in response to the pandemic. The survey participants gave us an insight into how dire the situation has been in the past few months. Among households in which at least one member was working in February, half reported not working at all in the previous week. Of those still working, 21% were earning less and 16% were working less.

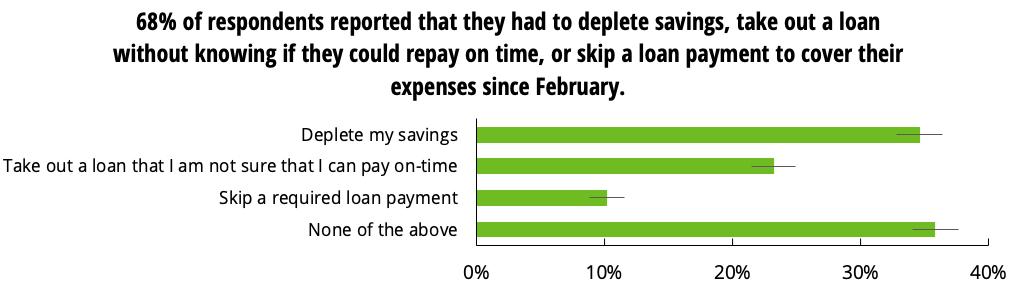

Households have struggled to cope with the loss of income. More than 30% told us they had depleted their savings; more than 20% had asked for a loan, formal or informal, that they were unsure they could pay back on time; and more than 10% said they had to skip an existing loan payment. One third reported having to reduce their portion sizes during meals more than three times in the past week, and 40% reported having to skip meals in the past week.

The Vulnerability of Informality

Colombia has made great strides toward poverty reduction in the past 20 years. While half of Colombians lived under the monetary poverty line in 2002, by 2018 that number had dropped to 27 percent. This is quite a feat, but for those who crossed the poverty line in one direction, there is no guarantee that they will not cross back.

Even though Colombia’s social safety net appears strong on paper, approximately half of Colombian workers are hired informally, meaning that they are likely paid below the minimum wage, are not contributing to health care or pension schemes, are not paid severance when fired, and are ineligible for unemployment schemes. Among the informal are also more than 1 million irregular Venezuelans living in Colombia, who are not able to take on formal jobs.

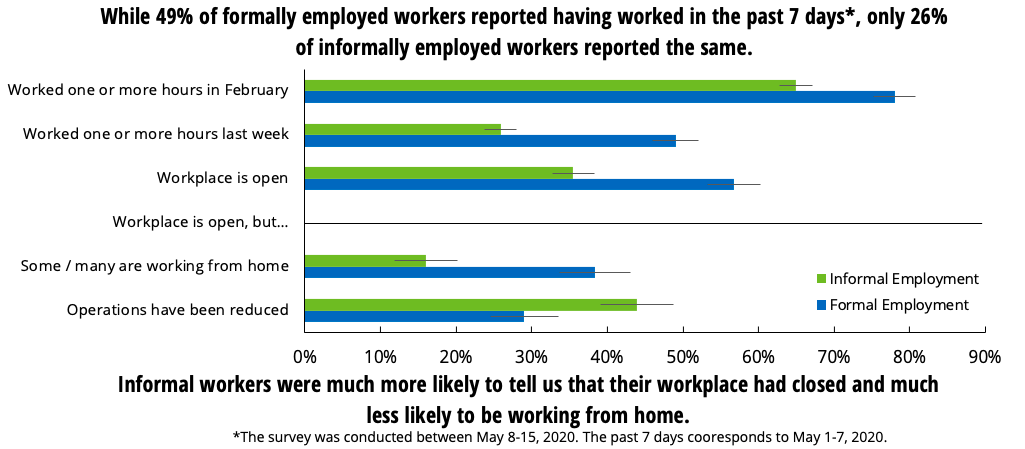

Like everywhere in the world, the most vulnerable have been hit hardest by the economic impacts of COVID-19, and in Colombia that has meant informal workers. Among the formal employees we spoke with, 49% told us they have worked in the past week, while only 26% of informal workers reported working. Informal workers were much more likely to tell us that their workplace had closed and much less likely to be working from home.

In great part because of informal workers’ loss of income due to the pandemic, researchers at the Universidad de Los Andes recently warned that COVID-19 may rewind the clock two decades in Colombia’s fight against poverty.

Stepping up to the Plate with Cash Transfers

A few days before imposing the lockdown, Colombia’s government created an emergency fund to finance health system expenditures, provide subsidized credit to (small formal) businesses, and support vulnerable populations with cash assistance. By leveraging existing conditional and unconditional cash transfer programs, such as Más Familias en Acción, Jóvenes en Acción, and Colombia Mayor, the government has been able to quickly target additional cash to households who need it most. Relying solely on these existing social protection programs, however, would have missed households falling into poverty because of the pandemic. As a result, the government created Ingreso Solidario, a program specifically designed to support low-income households hard hit by the pandemic and not eligible for existing programs.

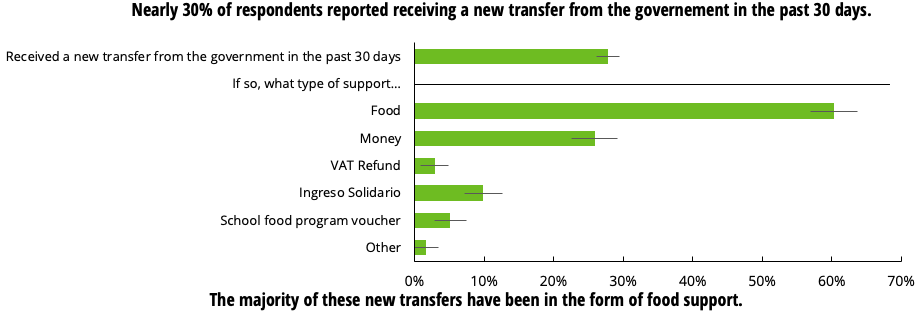

Is support actually reaching those who need it most? Of those we spoke with, 30% had received some type of food or cash transfer from the government that they had not received before the pandemic. Our survey suggests those in greatest need are indeed more likely to receive government aid—those with informal work arrangements and families with children were more likely to have received aid; although households with senior citizens were no more likely than other households to receive aid.

What Now?

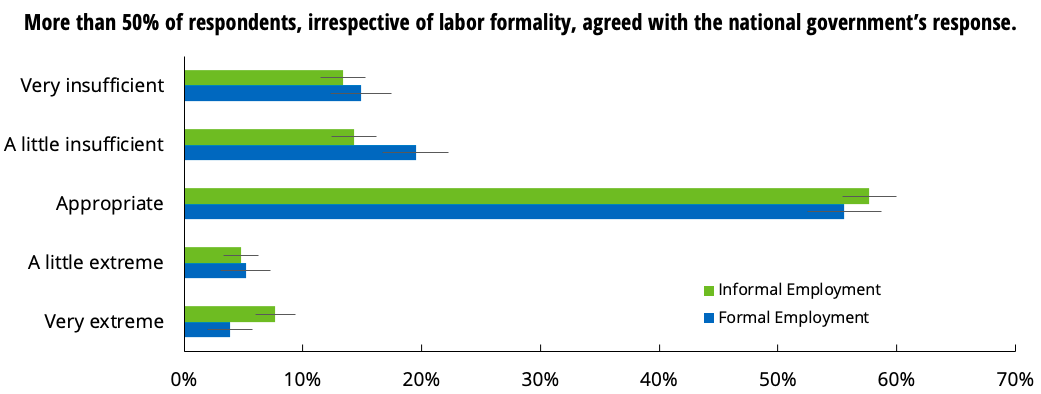

When surveyed in May, more than 50% of respondents—irrespective of whether they work in the formal or informal economy—reported that they agreed with the national government’s handling of the crisis. More than 70% told us they had stayed at home during most of the past seven days, and 80% said they had used a mask when leaving home during that time. However, Google Mobility data shows that compliance with mobility restrictions dropped around a month after the lockdown started on March 25.

If the government were to determine that the gradual opening of the economy needs to slow down, or that certain steps need to be reversed, citizens may not be as supportive of these policies and may not comply at the same level a second time around. The government has already spent around 1.9% of GDP on healthcare and countering the negative impacts of the lockdown. Much more may be needed to maintain popular support for, and compliance with, these policies and curtail a possible return to poverty for millions. As the pandemic lingers and places further strain on the state’s resources, it will become increasingly necessary to more precisely target cash transfers to those hardest hit by the economic slowdown.

This month, IPA and DNP will run a second wave of the panel survey and will once again publish the results online and disseminate them broadly. By re-interviewing the same households, we will be able to track changes in their economic situation as well as their perceptions and behaviors in response to the ongoing pandemic. As the Colombian government makes decisions around easing lockdown measures through selective testing/tracing/isolation (PRASS strategy), gradually reopening the economy, opening schools, extending social protection measures, and much more, we will aim to collect information that supports the government in making data-based decisions.

In addition to creating valuable descriptive data to help us identify and track the health and economic challenges that households are facing, we are working hard to provide decision-makers with rigorous evidence on what policies and programs provide the most cost-effective response. We are currently partnering with DNP to evaluate the impact of expanded social protection measures for vulnerable Colombian households, with Mercy Corps to evaluate the impact of a cash assistance program to vulnerable migrants ineligible for government transfers, and with the Colombian Institute for Family Welfare (ICBF) to evaluate the impact of an informational campaign designed to provide parents and caregivers with the knowledge and skills to support to their children’s learning process at home. Results are forthcoming, but you can read about these projects and many more on IPA Colombia’s website and the RECOVR Research Hub.

Listen to a podcast in Spanish on unemployment in Colombia, featuring Sebastian Chaskel sharing these results.