The Reach of the COVID-19 Crisis in Rwanda: Lessons from the RECOVR Survey

By Luciana Debenedetti, Doug Kirke-Smith, and Jean Leodomir Habarimana Mfura

Amidst the global fight against the coronavirus, Rwanda stands apart. Early and extensive measures—a strict nationwide lockdown from March 21 to May 4, pool testing, comprehensive contact tracing, and quarantining of cases—laid important groundwork for the country’s broad-based response. Rwanda also made headlines for incorporating technology into its response in a way that few other countries did, by deploying drones for disseminating health information and using anti-epidemic robots that can screen up to 150 people per minute for common virus symptoms including fevers and dry cough.

Rwanda mandated facemasks in public on April 19, and after the lockdown was lifted also instituted a curfew from 9 PM-5 AM. While the country had a relatively low and stable case count in the early months of the pandemic, it began to see a steady increase of daily cases beginning in June—consistent with the experiences of other countries that emerged from stringent measures. However, despite this increase, the country has tallied 2,540 cases total (as of August 17) and a mere 8 deaths.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, countries have worked to reduce prevalence as well as to mitigate the socioeconomic impact of lockdown and other measures that have slowed down economic activity. To better understand the impact of the crisis on the Rwandan population, IPA ran the first round of our RECOVR survey in Rwanda from June 4-12.

Similar to our approach in other RECOVR countries, we surveyed 1,482 respondents on a number of health, economic, and education outcomes by randomly dialing phone numbers in a sample that is representative of the set of active mobile phone numbers held by adults in Rwanda. A large portion of our respondents live in Kigali, the average age of the sample is 30, and 37 percent of respondents are female.

This blog post summarizes the key findings and their policy implications. More information about the RECOVR survey, a cross-country panel survey that is tracking the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 over time in nine countries, is available here.

Rwandans are concerned about their risk of contracting COVID-19 and have adjusted certain behaviors in response.

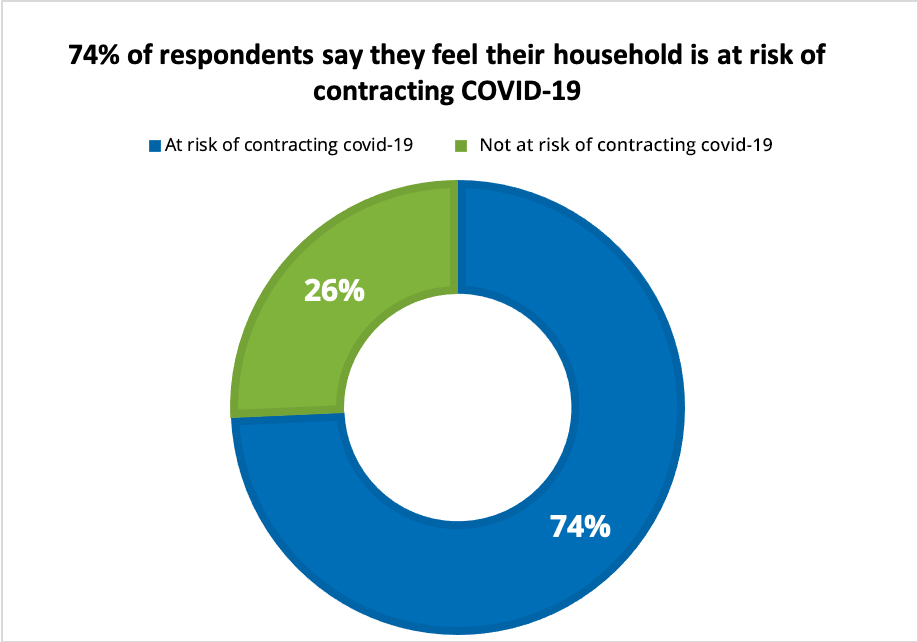

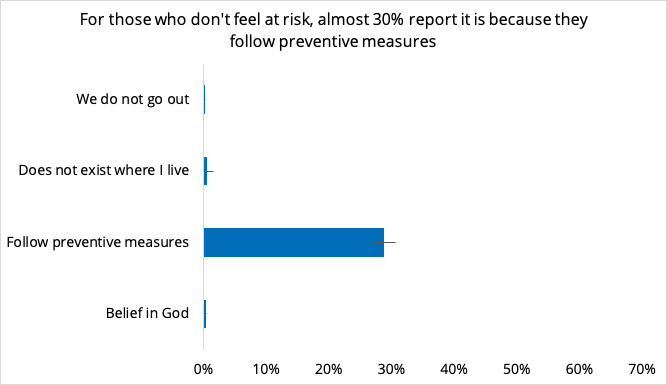

COVID-19 is a significant concern within our sample. More than 70 percent of respondents indicate that they feel their household is at risk of contracting COVID-19. Of note, poorer and wealthier households report comparable levels of concern—and, for those who don’t feel at risk, poorer and wealthier respondents are similarly likely to say it is because they are following preventive measures.

The percentage of respondents who reported that they consider their household at risk of contracting the virus was much higher than in similar samples in other countries (74% in Rwanda, while nearly 40% in Zambia, and 25% in Ghana). While we don’t know why this is—particularly against the backdrop of comparatively low case counts—it’s possible that the highly visible government response and stringent lockdown instilled concern for the virus in many Rwandans. In addition, the timing of the RECOVR survey coincided with the increases in case counts beginning in June and could have captured heightened awareness and fear from case increases.

In terms of behavior change and self-protection measures, respondents report high compliance with hand-washing. Specifically, 80 percent of respondents say they washed their hands more often the week they were surveyed than before mid-March. At the same time, 25 percent say they did not stay home any days in the last week (it’s important to keep in mind that the lockdown had been lifted for a month by the time the survey was conducted).

Respondents’ economic security has fallen sharply...

The effects of slowed economic activity are far-reaching and consequential. Almost 80 percent of respondents say they have had to deplete savings to pay for food, healthcare, or other expenses since February 2020. 80 percent of employed individuals have earned less pay than they did in a typical week before the government closed schools, and more than 60 percent of employed individuals have spent fewer hours working compared to a typical week.

Almost 80% of respondents say they have had to deplete savings to pay for food, healthcare or other expenses since February 2020.

Image by: The Noun Project (Guilherme Furtado, Gregor Cresnar, trang5000)

Rwanda’s different industries have suffered in varied ways. For example, more than 70 percent of respondents working in agriculture reported altered planting, harvesting, or marketing of agricultural products because of COVID-19-related restrictions and these respondents have primarily faced challenges in selling crops or livestock as planned. Respondents in manufacturing and retail (compared to agriculture/services) are most likely to report earning less pay than in a previous typical week, with more than 80 percent indicating this is so.

...and food security and livelihoods have followed suit

Hits to incomes and job security threaten food security, and the survey results reflect this dynamic. Almost 70 percent of respondents say they have had difficulty buying the amount of food they usually buy because household income has dropped, and more than 50 percent of households say they have had to reduce food consumption in the past week.

Not surprisingly, existing socioeconomic and geographic cleavages amplify such effects. Poorer respondents are more likely than wealthier respondents to report having to sell off their assets to pay for food, healthcare, or other expenses since February 2020. Rural respondents are more likely than urban respondents to say they have had difficulty buying the amount of food they usually buy because the price of food was too high or because there were shortages in the markets.

Education is a priority for the Rwandan government and households, and radio is a promising avenue for distance learning.

Across the world, lockdowns and school closures have necessitated distance/online learning, and Rwanda is no different. Encouragingly, households report that 80 percent of children in primary and secondary school are spending time on education at home since schools were closed, and more than 80 percent of households have received communication from the Ministry of Education and Rwanda Education Board. Among both children in primary and secondary school engaged in distance learning, 40-50 percent are using radio learning programs; for children in primary school, it is over 50 percent.

Importantly, there are differences between poorer and wealthier households’ education activities, with poorer households more often relying on Radio Rwanda and wealthier households accessing a variety of modes including TV (particularly Rwanda TV), WhatsApp groups set up by their schools, and internet-based programs. Poorer respondents are more likely than wealthier respondents to talk to children about school, read to children, tell children to review their books, help with homework, and encourage children to do distance learning while schools have been closed. Such differential access and usage of educational tools is an important finding to inform future offerings and channels for distance education.

Policy Implications and Looking Forward

What can be learned from the results of the RECOVR survey, and, more importantly, how can these findings be used by policymakers in Rwanda to inform the government’s responses for continued economic recovery? Below we suggest a few lessons and ideas for further research:

- Encouragingly, nearly 100 percent of respondents have access to a mobile money account, and this ubiquitous access is critical for future government assistance programs and remittances. With the elimination of charges for mobile money transfers instituted on March 19,1 mobile money is an avenue that stands to be further utilized for cash transfers and social assistance programs.

- When children return to school, how can policymakers and educators meet students at their learning level—especially given children’s varying levels of access to education support during closures? Targeted instruction—grouping children according to learning level and teaching to that level—may help, particularly for foundational literacy and numeracy. Rigorous research has shown that targeted instruction improved learning in Ghana, Kenya, India, and elsewhere.

- The upcoming lean season (September-November)—the period between planting and harvesting during which food reserves and labor opportunities typically decline—has serious implications for already-dire food security outlook in Rwanda. Indeed, the WHO has already raised the alarm for deepening risks of food insecurity and malnutrition across the continent. More than 70 percent of respondents working in agriculture have altered planting, harvesting, or marketing because of COVID-19 related restrictions, mainly citing challenges in selling crops and livestock as planned. Without supplemental income assistance for Rwandans or a strategy to assist the agriculture sector, these effects can only worsen.

IPA is conducting the second round of the RECOVR survey in Rwanda in September, which will enable policymakers to understand the range of medium-term effects that the pandemic has had six months into the crisis. Stay tuned for a webinar discussing the results of both survey rounds later this year.

1. Some fees, notably person-to-person transfers, were re-instituted in June. Payments to business accounts remain free.

Luciana Debenedetti is a Temporary Senior Policy & Communications Associate for IPA.

Doug Kirke-Smith is the IPA Rwanda Country Director.

Jean Leodomir Habarimana Mfura is the Research and Policy Coordinator for IPA Rwanda.