Evaluating Strategies to Improve Children’s Reading Skills in Kenya

Abstract

Many students in Sub-Saharan Africa are not learning to read in their first years of school and literacy rates remain low in the region. Researchers partnered with the Kenyan Ministry of Education to evaluate the impact of two strategies aimed at improving the literacy skills of school children in Kenya: enhanced literacy instruction, through teacher training and text message support, and child-to-child reading groups. Results showed that the enhanced literacy instruction improved children’s reading skills in both Swahili and English and reduced the school dropout rate by 50 percent. The reading groups led to a small improvement in children’s attitudes about reading, but did not significantly improve their reading skills.

Policy Issue

Although most children in Sub-Saharan Africa have gained access to free primary education over the last two decades, literacy rates remain low in the region. Across the continent, 47 percent of adults and 28 percent of young people aged 15-24 are illiterate.1 Data suggests that the problem originates in the first years of schooling; in many countries across the region children fail to achieve functional literacy in the first three grades of school. This research contributes to the evidence base on school-based approaches to tackle this issue. The most direct way that education policy can influence literacy development is through classroom instruction. Schools can also play a role in encouraging children to read more and to help each other to read. This evaluation examined both of those strategies for improving learning.

Context of the Evaluation

In 2003, Kenya adopted universal free primary education and most children now enroll in school. However, limited funding has led to increased class sizes, student-textbook ratios of three to one, and shortages of classroom space and teaching materials. 2,3,4 And, perhaps due to these challenges, many children are not learning to read effectively in their first years of school. For example, a 2010 assessment found that more than half of students in 3rd grade were unable to infer meaning from short passages of text.5,6

Details of the Intervention

Researchers evaluated the impact of enhanced literacy instruction and child-to-child reading groups (“buddy reading”) on the literacy skills of school children in coastal Kenya. The cluster randomized evaluation took place in 101 primary government schools in the Kwale and Msambweni districts of coastal Kenya.Researchers randomly assigned the schools to one of four groups: literacy instruction; buddy reading; both literacy instruction and buddy reading; or neither (comparison group). Thirty children from each school participated.

The enhanced instruction intervention (a component of the Health and Literacy Intervention, or HALI Project) supported teachers in developing the literacy skills of one cohort of children through the first two years of primary school. It included:

- 140 sequential lesson plans for literacy sessions in Swahili and English.

- Five days of professional development for teachers over two years.

- Ongoing support for teachers for two years through weekly text messages that provided brief instructional tips and motivation to implement lesson plans. Teachers also received a small amount of mobile phone credit (US$0.50) each week.

The buddy reading intervention took place after the instruction intervention when children had reached 3rd grade. It included:

- Having children in 6th grade (“mentors”) read with groups of 3rd graders (“buddies”) twice a week for six months.

- Provision of reading books in English and Swahili.

- Training for class teachers and mentors.

- The program aimed to provide more individualized reading support in small groups and more opportunities for children to read.

The evaluation of the literacy instruction intervention took place over two years and began when students where in 1st grade (January 2010). The buddy reading intervention was evaluated over six months in 2012 when the younger children were in 3rd grade and mentors in 6th grade.

Results and Policy Lessons

Enhanced literacy instruction

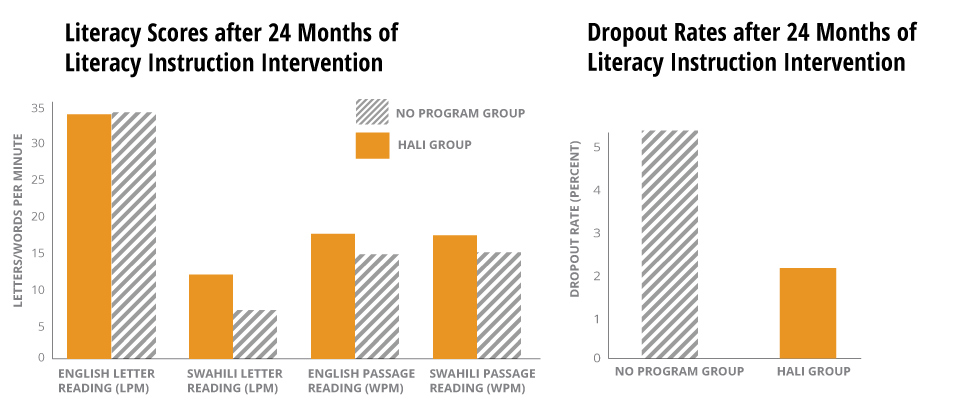

Literacy levels: Children who received the literacy intervention scored significantly higher in English spelling, Swahili letter reading, and the reading of words and passages in both English and Swahili. This improvement was achieved with no direct coaching for teachers and no books for students. The text message support reduced the cost of the literacy intervention, which was estimated at US$8.29 per child.

The researchers attributed some of the successes to teachers in the literacy intervention group spending more time teaching letters and sounds and less time focusing on whole sentences. Students in intervention classrooms spent more time reading and interacting with text and less time writing and copying from the blackboard.

Drop-out rates: Only 2 percent of the intervention-group children in the younger classes had dropped out of school by the two-year follow-up, compared to 5 percent of the comparison group.

Buddy Reading

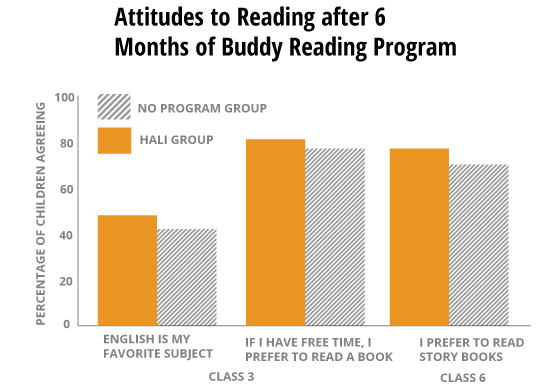

Reading levels: The Buddy Reading group did not significantly improve reading skills over a 6 month period for either mentors or buddies.

Attitudes about reading: As a result of the program, 3rd grade buddies were more likely to prefer English and to read in their spare time. Sixth grade mentors were more likely to prefer storybooks over textbooks.

Attitudes about the program: Teachers and studentsreported that the program improves reading culture, motivation for school and leadership skills.

This research provides several key policy lessons: first, a key aim of literacy instruction in the early years of school should be the systematic teaching of letter-sound correspondence and text interaction. Second, text messages may be a cost-effective way to increase motivation, monitor progress, and create support among teachers. Third, in areas where dropout is common, improved instruction may be an effective way to keep children in school. Lastly, because literacy development depends on children’s motivation to read as well as their ability to read, the child-to-child reading groups may be an important compliment to improved instruction.

Sources

1. UNESCO. EFA Global Monitoring Report: Youth and skills, putting education to work. Paris: UNESCO (2012).

2. World Bank. (2014). EdStats. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

3. Piper, B., & Mugenda, A. (2012). The Primary Math and Reading (PRIMR) Initiative baseline report. Research Triangle Park, N.C.: RTI International.

4. Sifuna, D. N. (2007). The challenge of increasing access and improving quality: An analysis of universal primary education interventions In Kenya and Tanzania since the 1970s. International Review of Education, 53(5-6), 687-699.4.

5.Wasanga, P. M., Ogle, A. M., & Wambua, R. M. (2010). Report on monitoring of learner achievement for class 3 in literacy and numeracy. Nairobi: Kenya National Examinations Council.

6. Mugo, J., Kaburu, A., Limboro, C., & Kimutai, A. (2011). Are our children learning? Annual learning assessment report. Nairobi: Uwezo.