The Reach of the COVID-19 Crisis in Rwanda: Lessons from Round 2 of the RECOVR Survey

As part of IPA’s ongoing RECOVR survey, we recently held a webinar with the Chronic Poverty Advisory Network highlighting key results of the second round of the surveys in Zambia and Rwanda. This blog post summarizes the main findings of the survey in Rwanda and policy recommendations. Click here for the blog for Zambia.

In both countries, there are pockets of progress with continued adherence to certain virus mitigation measures and promising acceptance rates for vaccinations. Education remains a key concern for parents of learners, with the prospect of potential learning losses. At the same time, as the pandemic continues, challenges remain with respect to food security and the long-term economic damage on livelihoods.

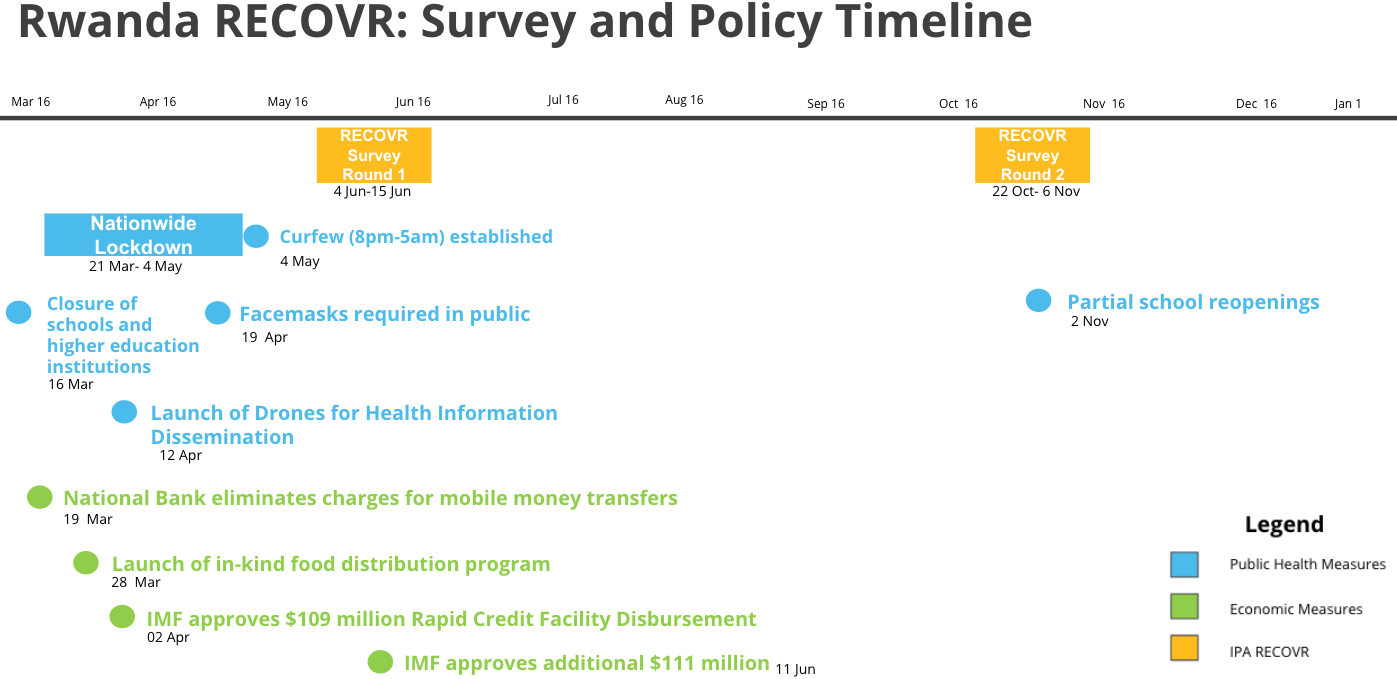

The second round of the Rwanda survey was conducted from October 22-November 6, 2020. Out of the 1,484 respondents from the first round, we ultimately surveyed 1,357 respondents. The timeline below outlines major policy responses and the country context of COVID-19 in Rwanda. At the time the survey was fielded, Rwanda had just crossed the threshold of 5,000 cumulative cases and 34 cumulative deaths reported.

Health

The vast majority of respondents across both rounds responded that they were concerned about COVID-19 (78 percent in Round 2 and 75 percent in Round 1). Accordingly, adherence to certain protective measures was also very high: 94 percent of respondents reported always using a facemask. However, 50 percent of respondents reported having gone outside their homes or receiving visits every day in the past week, mainly to go to work or markets, with men 14 percentage points more likely than women to report going out every day.

Eighty-five percent of respondents indicated that they would take a COVID-19 vaccine once it becomes available. At the time of the Round 2 survey, major vaccines around the world were still in clinical trials and no vaccines had been approved in Rwanda. The majority of respondents would take the vaccine for self-protection, followed by family protection. The majority of respondents listed doctors, health workers, and the ministry of health as their most trusted source of information, with fewer than 1 percent expressing trust in friends, religious leaders, or celebrities (34 percent said they did not trust anybody). These numbers suggest that acceptance in Rwanda is relatively high, and when vaccines are distributed en masse in Rwanda, public health messaging campaigns will be well served by highlighting health experts more than politicians or culturally significant figures.

Food Security and Financial Resilience

Survey data on social assistance and households’ ability to weather the financial impacts of the pandemic suggest that poor/non-poor and rural/urban cleavages are differentiating factors in Rwandans’ economic experiences in recent months. For example, a higher share of respondents from urban areas report reducing portions for adults (60 percent ) and children (79 percent) in their household. At the same time, respondents from rural areas are more likely to be unable to buy as much food as they usually do because of high food prices and reduced income.

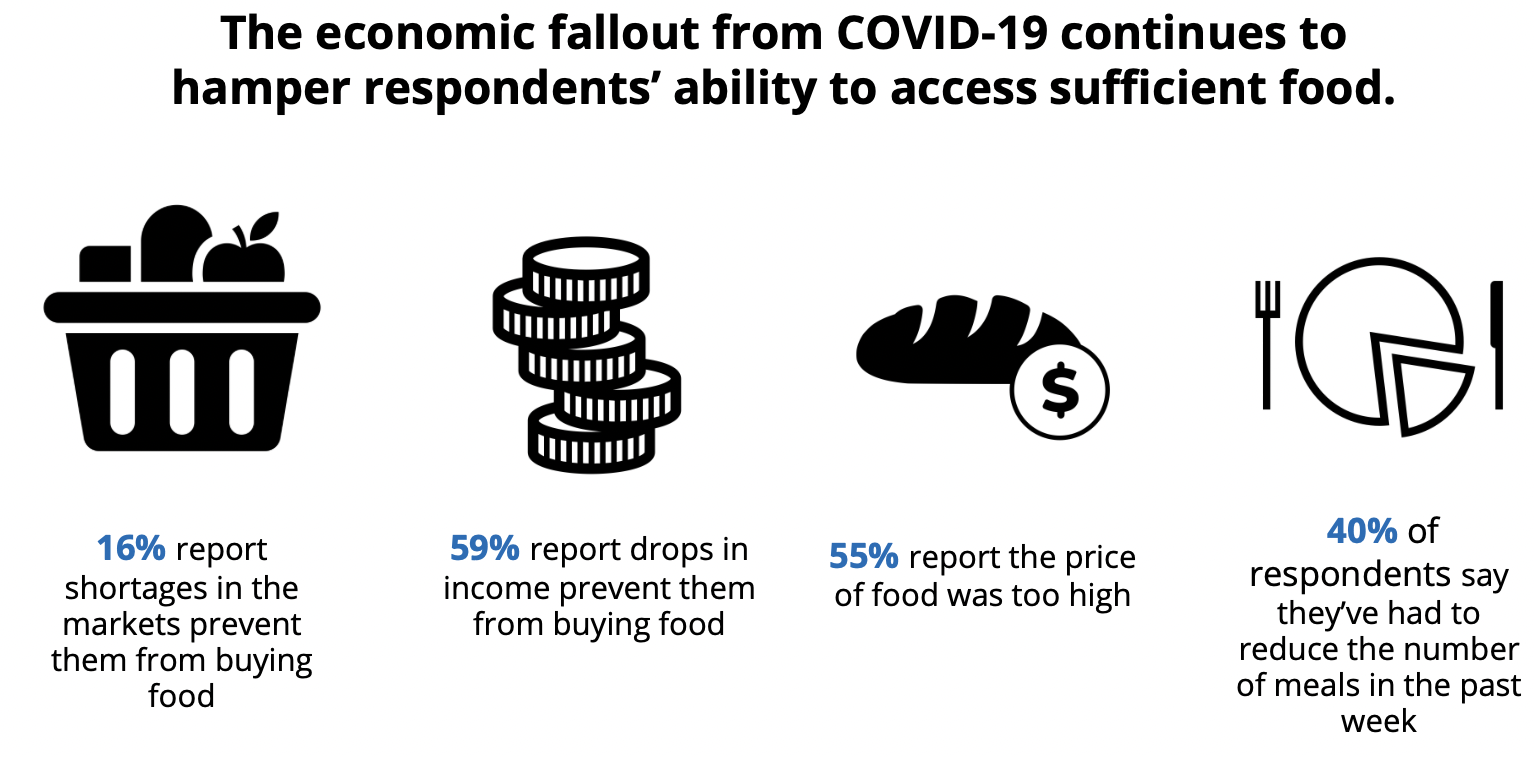

Between June and October, there was a 6 percentage point decrease in the share of respondents limiting portions at mealtimes from 50 percent to 44 percent, while 40 percent in Round 2 said they’ve had to reduce the number of meals in the past week. As we see from the figure below, income drops and high food prices (whether through price increases, or income drops that make food comparatively more expensive) seem to drive food insecurity more than market shortages (16 percent). Finally, the proportion of respondents needing to deplete their savings to cover basic expenses decreased by 17pp (79 percent in Round 1 and 62 percent in Round 2); of course, this is still more than half of the sample, and thus an important indicator of economic fallout that policymakers should continue to monitor.

Education

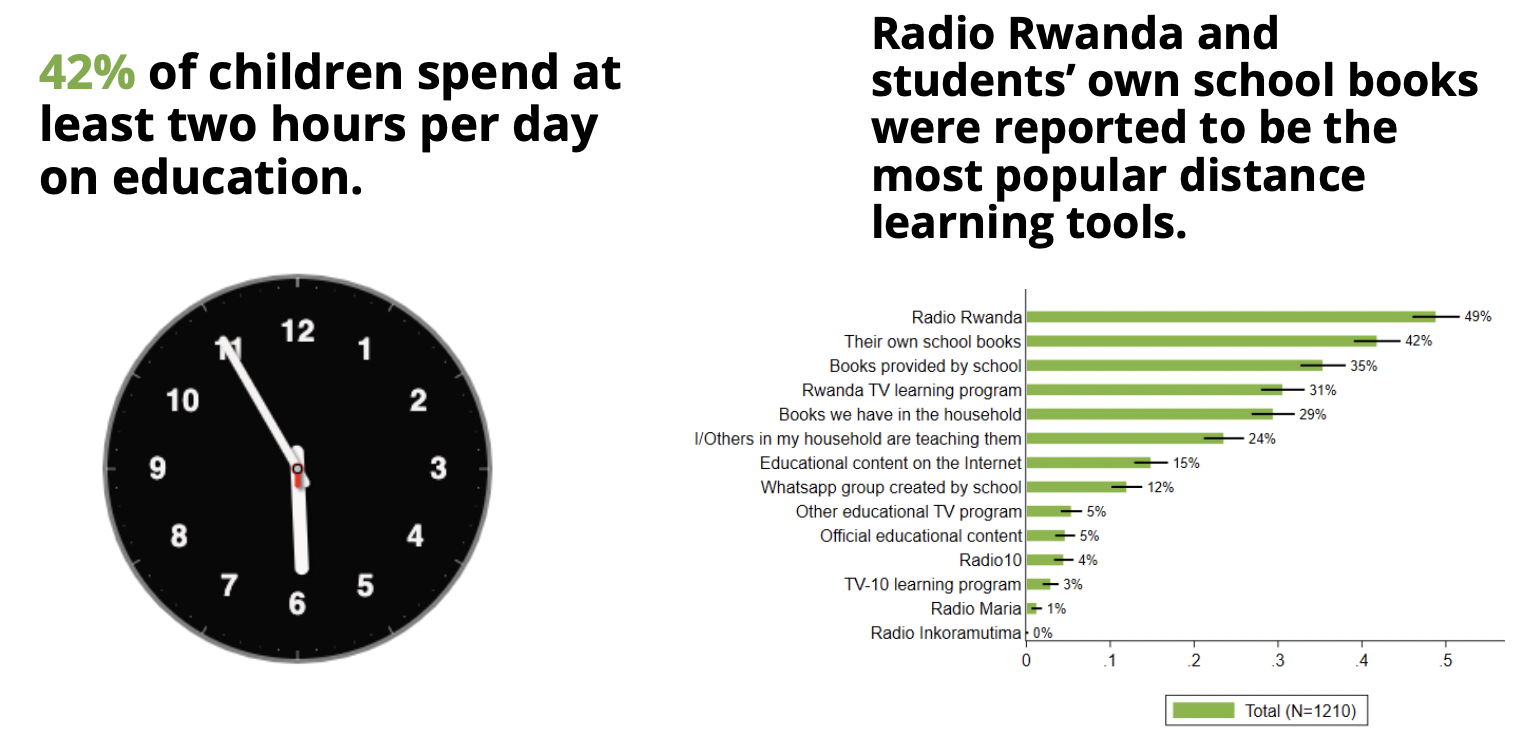

The rapid introduction of distance education placed new demands on students, their families, teachers, and the Rwandan education system at large, and concerns with education were reflected in the survey. For example, the majority of parents prefer in-person schooling next year, and nearly 100 percent of children were to be enrolled for in-person classes in November. Nevertheless, distance learning was considered by 92 percent of parents to be effective or very effective.

In terms of learning tools, Radio Rwanda (49 percent) and students’ school books (42 percent) were reported to be the most popular distance learning tools. Respondents below the poverty line are more likely to say they use the radio and less likely to say they use the internet.

Economic Activity and Employment

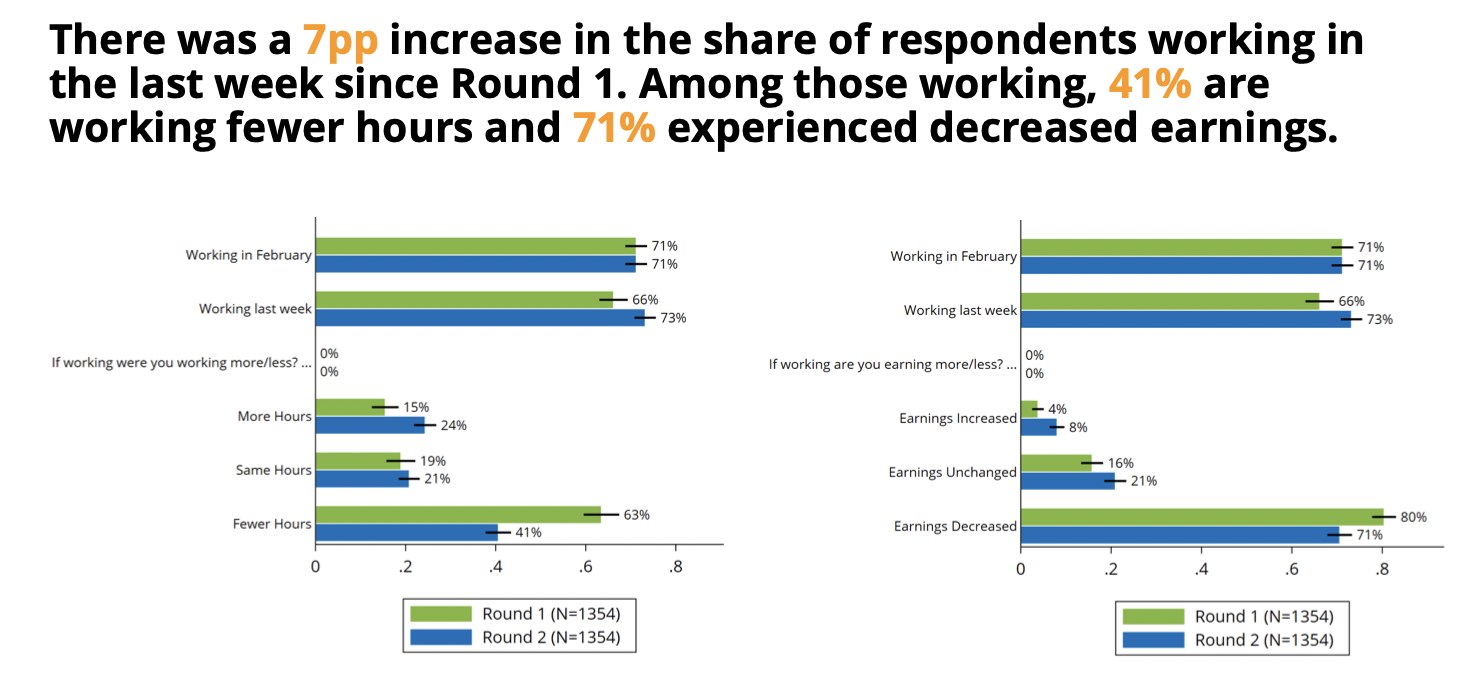

Across the survey rounds, employment has remained largely stable, though earnings and hours worked for those employed have been less consistent. For example, 69 percent of respondents’ place of work from February remained open in November, only a slight (non-significant) decrease from 71 percent in June. Agriculture remains the sector where the largest share of respondents’ workplaces are still open, though this rate decreased by 13 percentage points across rounds.

In terms of changes to labor market participation, there was a 7 percentage point increase in the share of respondents working between rounds 1 and 2 and, of those working, 41 percent are working fewer hours—but this represents a 22 percentage point improvement since Round 1. 71 percent of those still working also report decreased earnings. Lastly, Poor respondents and heads of household from rural areas are more likely to be self-employed or have worked on a family business or farm in the past 7 days.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

Social Protection

As mentioned during the webinar and the Zambia blog, when assessing Rwanda’s social protection offerings, policymakers can consider: which individuals will be offered new or expanded social protection benefits; how such individuals can be identified, verified, and enrolled in a social protection program; whether benefits should be provided as cash transfers or in-kind transfers (e.g. food); and, if cash transfers are selected, whether they should be provided through digital or physical channels. These recommendations are further outlined in IPA’s policy brief Key Decisions for COVID-19 Social Protection in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.

Education

The results from RECOVR Round 2 paint a picture of acute impact, which necessitates evidence-based policy responses for immediate help and long-term recovery. With returns to school, educators will be challenged to meet students at their learning level, especially given children’s varying levels of access to educational resources during school closures. For example, one-on-one simple oral reading assessments enable teachers to understand students’ levels, to inform tailored instruction. These assessments should be conducted periodically to track students’ progress. Fast, simple, and cost-effective assessments available to educators include ASER, ICAN, and Uwezo.

Targeted instruction, also known as the Teaching at the Level of the Child approach, in which students are grouped according to their learning level and are taught at that level, may also assist in the long-term transition back to in-person learning. Targeted instruction is especially effective for foundational literacy and numeracy skills, which will be critical to reinforce to ensure that younger students especially have the necessary foundations to progress in their education. Rigorous research has shown that this educational strategy improved students’ learning in Ghana, Kenya, India, and elsewhere.