Getting Governments to Use Evidence through the Embedded Evidence Labs

This blog is based on the forthcoming study “How Embedded Labs in Education are Promoting the Use of Data and Evidence” and is part of a three-part blog series of our campaign, Do More With What Works.

Ever planned to hit the gym but ended up watching Netflix instead? We have all been there. Change is hard, not because we lack good intentions, but because it takes drive and a supportive environment.

The same thing happens with governments. Public officials may genuinely want to create better policies using evidence of what actually works. But even with the best intentions, a complex system and institutional inertia often get in the way.

This matters because governments reach millions of people through their policies and programs. In today's world of declining development financing, there is a massive opportunity to maximize impact by helping governments use their national budgets more effectively—investing in programs that are proven to work.

Helping governments use evidence requires a multi-pronged approach—one that not only fosters policymakers’ willingness to use evidence but also addresses the systems in which they operate.

To address this challenge, IPA is supporting 24 governments across eight different sectors in establishing their Embedded Evidence Labs (Labs), teams that work within government to systematically connect research with decision-making.

In this blog, we describe how these Labs not only generate evidence but also address individual, group, and systemic factors to support its effective use in policy. Join us to see how we can help get governments to the gym!

The Squid Game: The Journey of Evidence Within Government

If we look at how evidence is used in public institutions, it often resembles the hit Netflix show Squid Game. In the series, participants race through a high-stakes, trap-laden course, and only one makes it to the end.

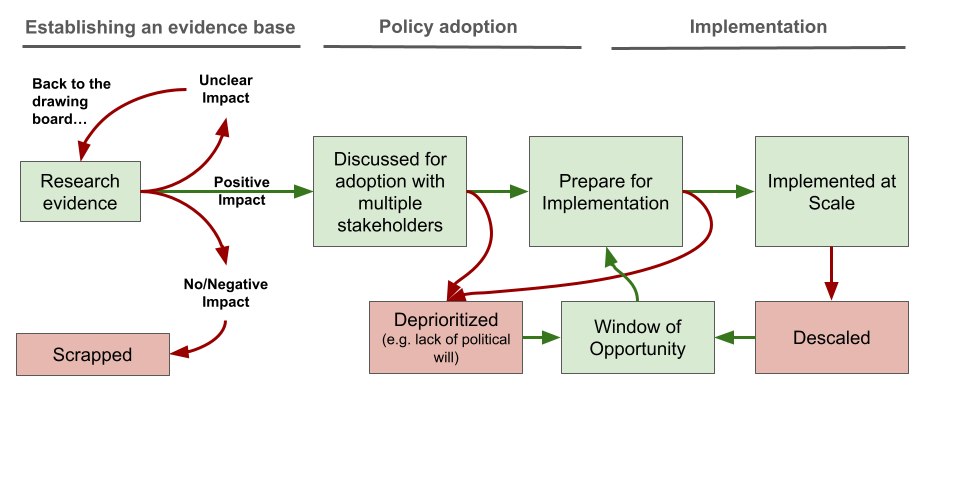

Efforts to inform policy with evidence face a similarly brutal path. Figure 1 gives us a simplified view of just how chaotic and messy the journey of evidence through government can be, often failing to reach its intended destination.

Figure 1. A simplified version of the journey of evidence within governments

Establishing an Evidence Base: From the very beginning, the journey of evidence can be short. For example, evidence might show that a new policy is ineffective and therefore gets scrapped—a relatively good outcome. Or the evidence is promising but inconclusive, and further research is needed.

Policy Adoption: Let’s assume the evidence demonstrates that the policy is effective. The next step is for decision-makers to adopt it. But who exactly are these decision-makers? Are they technical experts or political leaders? Who will champion its inclusion in the budget? Will they trust the results? If the decision-making structure—including the interests at play, as well as the power dynamics and capacity that shape actors’ understanding, willingness to embrace the evidence, and commitment to change—is not clearly identified and addressed, there is a significant risk that the evidence will be sidelined or deprioritized. Adoption (also referred as uptake) is defined as the intention, initial decision, or action to try or employ an innovation or evidence-based practice. Learn more

Implementation: Assume the relevant stakeholders adopt the policy—then comes implementation. It must be carried out effectively and sustained over time. How will it be embedded in the agency’s operational structure? How will it be monitored and adjusted to achieve fidelity of implementation? Who will advocate for its continuity when political priorities shift or administrations change? Implementing a new policy requires changes in how the system operates internally, as well as ongoing support to ensure it is implemented correctly and sustainably; otherwise, there is a risk that the policy will be ineffective or discontinued.

A Real-World Example: Peru’s Education Ministry

Let’s take the case of the Decidiendo por un Futuro Mejor (DFM) program, one of the initiatives supported by the Embedded Lab at Peru’s Ministry of Education (MineduLab).

The Lab evaluated a video-based strategy aimed at changing students' perceptions about the value of returning to school. The strategy proved effective in reducing dropout rates. This led to an initial scale-up in 2018, when the videos were integrated into the “full school day” secondary education program. However, due to changes in the program implementation model, the video component was discontinued.

It wasn’t until 2021 that the strategy was scaled up again, this time as part of the Ministry's remote education strategy during COVID-19 school closures. With reducing school dropout becoming a priority during the pandemic, a political window of opportunity opened, allowing the evidence-based intervention to gain support and be re-implemented, with the videos broadcast nationwide on public television.

This story illustrates that the use of evidence is not a linear process. It goes beyond research and dissemination. Multiple actors with different interests make decisions at different points in time. Using evidence often requires systemic changes, like budget or implementation strategies adjustments, that evolve over time.

Out of many promising ideas, only a few are scaled—and even fewer are sustained.

A Multi-Pronged Approach: Combining Linear, Relational, and Systemic Strategies

Adoption and sustained implementation of evidence informed policies requires strategies that address multiple, interrelated challenges simultaneously. Labs aim to do exactly this. Labs are government-based teams that work alongside decision-makers to identify problems, generate data and evidence, and support their use. Through their activities, Labs combine linear, relational, and systemic strategies to facilitate the use of evidence (Best and Holmes, 2010).

From a linear perspective, Embedded Labs co-design research agendas and study designs with system stakeholders (e.g., government units that design and implement policy), implementing evidence generation and learning strategies, and carrying out strategic dissemination through user-friendly, actionable formats (e.g., policy briefs) and diverse communication channels (e.g., workshops).

This approach is enhanced through relational strategies, in which Embedded Labs build partnerships with key actors involved in evidence generation and use, supporting them in developing the skills and knowledge needed for effective engagement. For example, for a specific project, Labs create collaborations between academic researchers and education policymakers and implement capacity-strengthening activities, such as training in evidence-generation methodologies, ensuring that partnerships are well-equipped to co-design, decide on, and implement evidence-informed policies. These projects are co-designed, focusing on policy-relevant questions identified with the policymakers and incorporating their knowledge and goals into both the design and implementation.

Additionally, Labs adopt a systems approach that acknowledges the organizational context in which evidence is generated and used. Recognizing that these actors function within institutional frameworks, Labs address organizational conditions necessary for implementing evidence-informed policy. Being teams within the government allows them to understand not only the government’s processes and timelines but also the power relations and narratives that influence decision-making. For example, when scaling an evidence-informed intervention, e.g., teacher training, a Lab team may support the development or enhancement of government agency information systems to enable monitoring of policy implementation, thereby ensuring fidelity and effectiveness at scale. They may also help the government units advocate for political support and changes in legal frameworks or operation manuals among other activities.

Case study - the Rwanda Education Embedded Lab

An example of how Labs combine linear, relational, and systemic approaches is the case of the Rwanda Education Embedded Lab. This Lab operates under the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC), in close coordination with the National Examination and School Inspection Authority (NESA) and the Rwanda Education Board (REB).

The Lab is supporting the scale-up of performance-based teacher contracts. The program, which was rigorously evaluated in collaboration with researchers from Georgetown University and IPA, showed improvements in both teacher performance and student learning. Following these positive results, the Ministry asked the Lab to scale up the program while testing different delivery methods to identify the most effective approach, using randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—a key example of a linear approach to evidence uptake.

At the same time, the Lab applies relational and systems approaches. For example, the systems approach focuses on developing information systems such as the Comprehensive Assessment Management Information System (CAMIS) and the Teacher Management Information System (TMIS), as well as by building capabilities and developing a MEL system to ensure quality implementation at scale. The relational approach includes coordinating across government agencies—such as the Rwanda Education Board and the National Examination and School Inspection Authority (NESA)—and advocating to maintain the prioritization of scaling efforts at all levels within these agencies. Together, these approaches resulted in the incentive scheme reaching 4,762 teachers and 207,523 primary school students by 2023.

Even with all these strategies combined—as the DFM case shows—success often depends on being in the right place at the right time and seizing windows of opportunity. This requires a permanent presence within the system and the trust needed to be invited into key meetings where decisions are made—something internal teams are uniquely positioned to do.

Conclusion

The journey from evidence generation to large-scale, sustained implementation is complex. It requires multi-faceted strategies that go beyond producing and sharing evidence. Relational and systemic dimensions are key.

Using evidence means changing the system—a system made up of people and groups with diverse interests. Embedded Evidence Labs, as internal actors that build alliances both inside and outside the system, and that maintain a long-term presence within it, are well positioned to facilitate this kind of systemic change.

For over a decade, IPA has supported governments in establishing Embedded Evidence Labs. We are currently working with 24 government agencies to co-design and institutionalize their Labs. These partnerships span education, health, environment, and other sectors critical to poverty reduction.

The evidence is clear: when governments systematically use data and evidence to inform their policies, they can more effectively serve millions of citizens. The challenge is not just generating evidence, but ensuring it sur vives the journey from research to implementation.

In the next blog in this series, we’ll discuss IPA’s approach to co-designing and institutionalizing Labs within government, creating systems that facilitate the incorporation of evidence into the decision-making and implementation processes.