Can You Spot a Scam? Putting Fraud Attempts to the Test in Kenya

By Elif Kubilay, Eva Raiber, and Lisa Spantig

“Click the link to claim your prize!”

“Please call to update your account information today or it will be closed.”

“Get an instant loan of $100 by calling this number.”

These types of fake text messages are inescapable if you own a phone. Reading the messages right now, they may seem like obvious fakes, but for some consumers, scam identification on their phones is not as easy as it seems. Scammers often pose as legitimate financial providers to trick customers into sending money or personal information, which can lead them to mistrust digital financial services and hurt their overall financial well-being.

To develop more effective fraud prevention tools, our research team, which also included Jana Cahlíková and Lucy Kaaria, tested digital finance consumers’ abilities to identify phone scams in Kenya. Our tests found that information campaigns may not be as effective as we once thought.

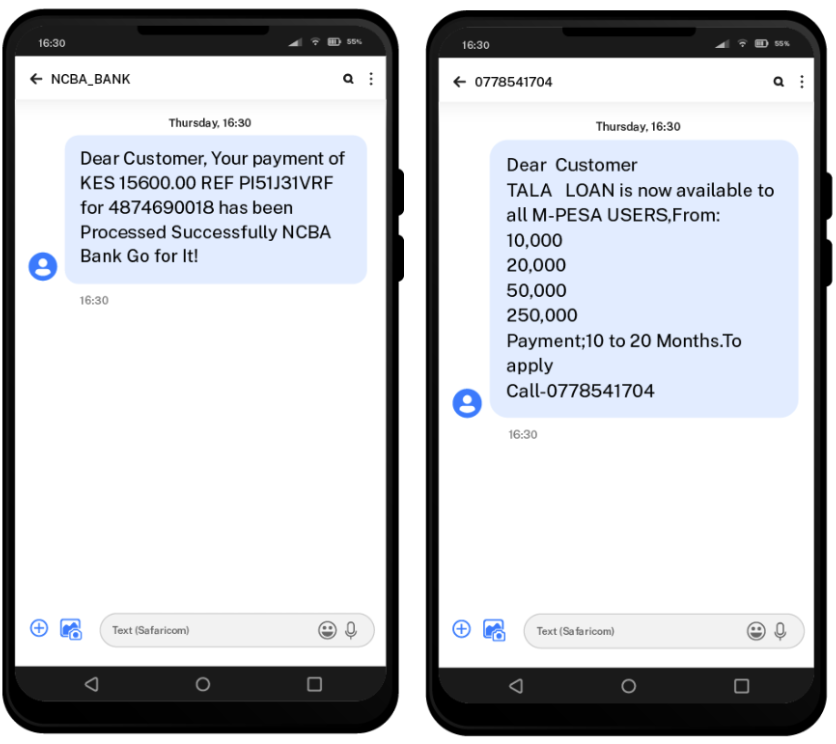

To measure people’s ability to identify scams, we showed 1,000 respondents of an online survey of 12 text messages. For each message, we asked if they thought it was a scam or not. The messages were actual scam-related public posts from Facebook and Twitter that were sent from accounts located in Kenya. We analyzed the text of the posts to identify those talking about scam messages, as well as official text messages, that are routinely sent by banks, mobile money providers, or phone service providers. We chose messages that represented different topics, such as making a wrong transfer or opportunities for jobs or investment.

How well could respondents identify scams? Out of the 12 messages, participants only identified 8.6 correctly on average. Yet, only 2 percent of the respondents classified all messages correctly. And 11 percent only correctly identified 6 or fewer messages.

We found that those who use digital financial services more did slightly better at distinguishing between legitimate and fake messages, presumably due to more exposure and experience with scam messages. Women did somewhat worse than men. But the largest difference in scam identification is linked to knowing someone who has been victimized. On average, respondents who knew a scam victim correctly identified 0.26 more messages.

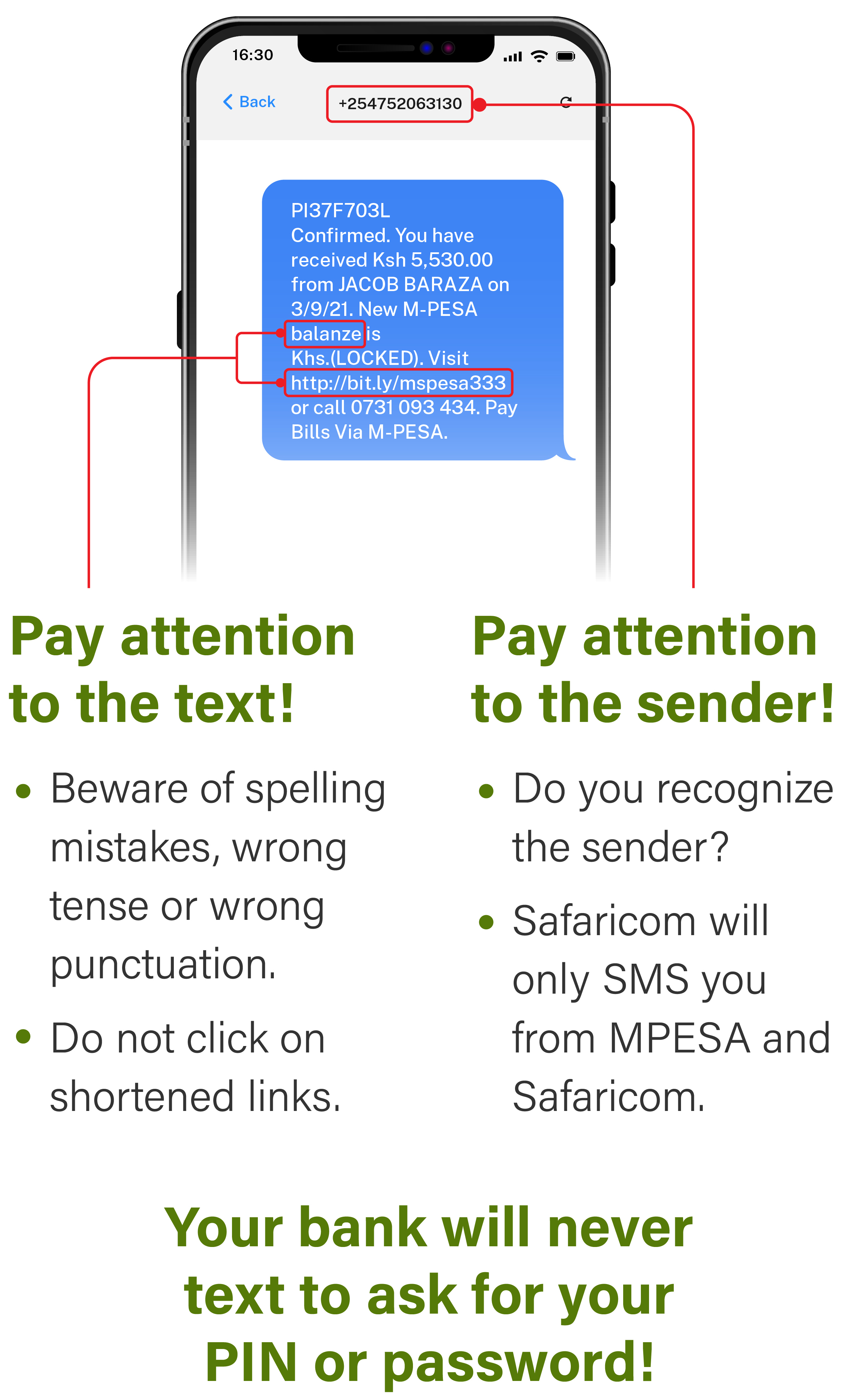

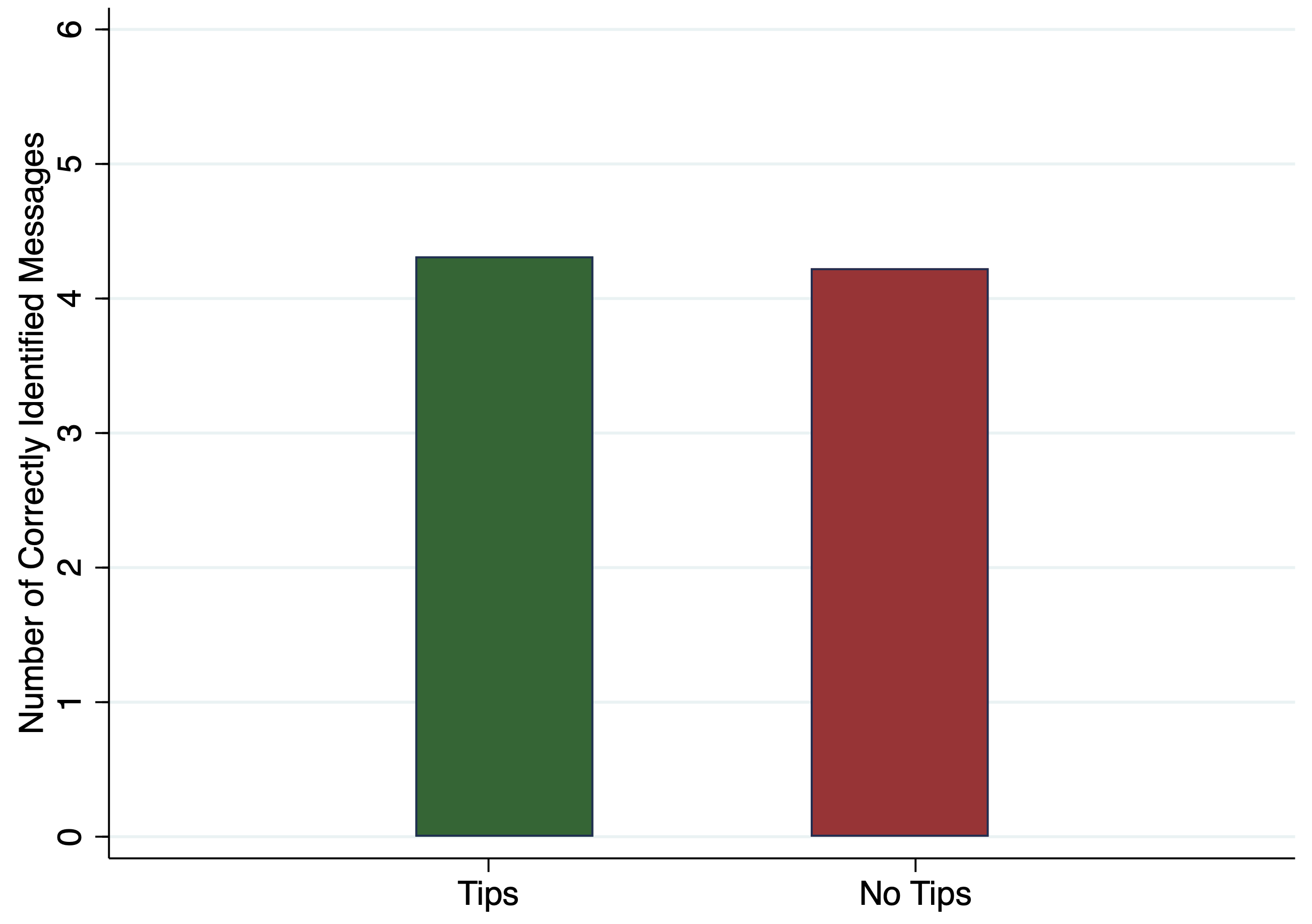

We also tested whether providing tips on how to spot scams increased scam identification ability. After classifying 6 out of the 12 messages, we provided tips to a random half of the respondents. These tips are based on previous awareness-raising campaigns on phone scams.

What effect did these tips have on the correct classification of the remaining 6 messages? Comparing those who received the tips and those who did not, we did not find significant differences in terms of how many messages were correctly classified.

Yet, those who received the tips classify more messages as scams—they become more cautious. If this generalizes to users’ daily experience it might imply that official messages would be less likely to be identified as genuine, making it more difficult for organizations to communicate with their customers.

So now you might be asking yourself, are awareness campaigns really the best way to protect consumers from scams? Are there better interventions for consumer protection, such as learning from peers’ experiences? We’d also like to know. That’s why our next steps will be to take it to rural Kenya. We hope to see whether or not information campaigns versus learning from peers produce any different results amongst survey respondents. We’ll keep you posted on what we find.