What Do We Mean When We Say “Distance Learning” and Why Does it Matter?

By Sarah Kabay, Olga Namen, and Stephanie Wu

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, over 188 countries instituted country-wide school closures. As a result, countless education systems and educators are trying to find alternatives to the classroom. At IPA, we support and partner with several Ministries of Education and have been looking for research and evidence that could help inform our partners during these challenges, the scope of which nobody's ever encountered before.

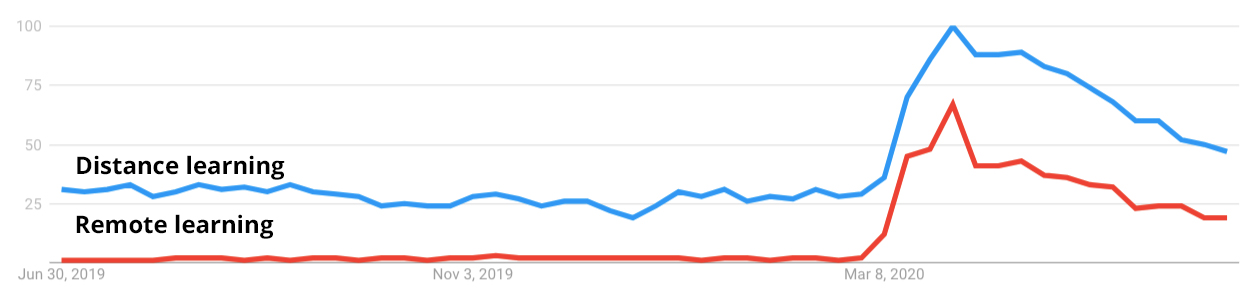

We started by asking ourselves, what exactly are we looking for? “Distance learning” is one of the most popular terms being used at the moment. We can see in Google trend data that searches for “distance learning” (in blue) quadrupled between February and March of this year. “Remote learning” (in red) though slightly less popular, reflected a similar spike in interest.

Traditionally, distance learning has been defined as when an instructor is located in a different place from the learner. Often discussed with other terms such as virtual, online, or open learning, distance learning emerged along with the technologies that enabled it. It is important to distinguish distance learning from online learning, though, which can take place in a classroom with a teacher present.

Some kinds of distance learning can be effective, but they’re not all the same

Various education technology interventions have been shown to be very effective, enabling students to move at their own pace and receive immediate and individualized feedback, but they often take place within the structure and supervision of classrooms or afterschool programs. For example, in Mexico, telesecundarias have been operating since 1968 and typically serve 1.4 million students, or just over 20% of junior secondary students. In that model, students assemble together in classrooms, but the lessons are simultaneously broadcast across the country according to a pre-established schedule and a maestro monitor, or supervisor teacher, facilitates class discussion. Telesecundarias have been found to increase educational attainment, enrollment, and even employment compared to traditional schools in marginalized locations. However, distance learning programs that are completely remote, tend to have relatively high dropout and failure rates and students with learning disabilities may be particularly disadvantaged.

The picture may be different depending on age

So far the vast majority of distance learning has focused on late-primary, secondary, or tertiary students—and it might matter that the term is now being used for much younger children. This is because in-person teaching might be especially important for young children’s learning. Several studies have demonstrated that infants can learn second language skills from in-person interactions, but not from television or audio-only recordings. Along with some findings from neuroscience, this research has inspired the theory that the earliest phases of language acquisition require social interaction. Though it is well known that infants’ brains are uniquely sensitive to external influence, a growing field of research is drawing attention to the fact that children’s brains undergo a possible second period of plasticity—when their brains are particularly sensitive to experience and environment—in adolescence. It’s possible that in-person interaction with peers and teachers is critical for older children’s learning as well. Younger children might also lack the autonomous learning skills and self-control required to thrive in a distance learning environment.

The message is in the medium

This issue of social interaction brings up another important concern: that distance learning traditionally refers to a situation in which a teacher is directly engaged with students and in which students can interact with the teacher. This might resonate with certain current experiences such as the “Zoom classes” currently being conducted by teachers in various high-income countries, but it is quite different from the experience of other countries where educational content is being played over the radio or television without a direct connection between teachers and students.

The latter, a broadcast of pre-recorded content, might align more with research on educational media. There is some research to suggest that exposure to educational media programs can improve literacy and numeracy and even communicate the importance of health behaviors such as washing hands. But in many countries, significant populations of children do not have access to televisions, radio, or even reliable access to electricity or network coverage. The coronavirus pandemic has left an even deeper divide with regards to digital usage, with less than 10% of the 450 million children in Africa enrolled in any kind of ed-tech program in March 2020. Countries with smaller populations and especially non-English speaking countries are particularly underserved.

New research from IPA, working with Peru’s Ministry of Education and the Inter-American Development Bank surveyed over 8,000 parents (along with teachers and principals) across the country to see if and how families were using the Ministry’s remote teaching services (offered in Spanish and nine indigenous languages). The researchers found that the majority used television broadcasts (78 percent), but almost the same numbers were using the internet (22 percent) as radio (20 percent). This suggests that even within the same country, it’s probable that students are learning through different mediums, which may ultimately affect what they’re learning.

In addition, the vast majority of research on educational media has focused on high resourced settings. As noted in a study from 2018, at that point, “Besides the literature on Sesame Street's international productions, no published research, to date, exists on the impact of children's media created in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).”

What about the parents?

A critical concern for any distance learning initiative is how to involve parents. Traditionally, the term “homeschooling” has been defined as when parents are responsible for educating their children at home instead of having children go to school. This term originated as a relatively small movement in the US in the 1960s, and homeschooling is illegal or highly regulated in many other parts of the world. Even in the US, very little research exists on homeschooling, though it has grown in popularity. In 2016 in the United States, charter schools, a very popular subject of education research, had 3 million children enrolled; in the same year, 1.7 million children were homeschooled, though it is far less frequently the subject of research.

The diversity of home environments necessitates an important discussion around inequality. Highly educated and more affluent parents have more resources to devote to children. The skills gap between children of high and low socioeconomic status widens while schools are closed. To try to mitigate the situation, IPA is currently conducting a study with the Inter-American Development Bank and education ministries in five Latin American countries to provide text messages to parents with actionable advice to improve homeschooling and facilitate their involvement in their children's education.

Maybe we can use the increased awareness of inequity that the current situation has generated to advance these initiatives and think about this work moving forward. Even when schools are open, researchers estimate that children spend only 10-20% of their waking hours in school. Strengthening the home learning environment will be incredibly important, in addition to the work to support teachers and governments as children return to schools with dramatically different levels of learning and wellbeing. As we continue to review and communicate evidence to partners, we are careful to note the distinctions between these different terms—distance learning, edtech, educational media, homeschooling—how they translate into key concerns for specific policy and practice moving forward.

Sarah Kabay is the director of IPA's Education program.

Olga Namen is a Postdoctoral Researcher at Universidad del Rosario and IPA.

Stephanie Wu is a recent graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and a summer intern with IPA's Education program.