How Ghanaians are Coping With COVID-19: Five Lessons from the RECOVR Survey

By Charles Amoatey, Elliott Collins, and Madeleen Husselman

In March, Ghana, like much of the world, adopted social distancing measures to slow the spread of COVID-19. Measures included the closings of schools and universities, suspension of gatherings of over 25 people, and partial lockdowns in major urban areas.

So far, like most West African countries, Ghana has avoided the worst of the virus’s health toll. However, in low- and middle-income countries like Ghana, the pandemic’s socio-economic consequences may exceed the immediate health ones and even cost more lives. Losses in employment, business slowdowns, interrupted education, and food insecurity threaten to have both short- and long-term consequences.

To better understand how people’s lives are being affected by COVID-19 and to enable data-driven policy response, IPA developed a panel survey called the RECOVR Survey which is being run in Ghana and 8 other countries. In Ghana, we have been working with a host of government partners—the Ghana Statistical Service; Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection; Ministry of Education; Ghana Education Service; and National Board of Small Scale Industries—to understand what data decision-makers need to respond effectively to the pandemic’s wide-ranging impacts.

Last week, we hosted a webinar to share findings and policy perspectives from the first round of the RECOVR Ghana survey, conducted from May 6 to May 26 (a recording is available here). The survey’s sample comprised 1,357 respondents, reached through random digit dialing of a nationally representative sample of numbers. (As is typical with this method, the sample of numbers ultimately reached was not representative of the national population: in this case, it was younger, more male, more educated, and more urban than Ghana as a whole; household size was comparable.) This blog post summarizes key takeaways from the survey.

Households are aware of the recommended preventative measures, and large majorities self-report that they are following them.

Respondents were asked if they feel that someone in their household is at risk of contracting COVID-19. Only twenty-five percent responded “yes” while of the remainder who responded “no,” the vast majority—92 percent—said they did not feel at risk because they follow preventative measures, with small minorities citing other explanations such as belief in God or the virus not existing where they live. Beliefs were similar across poorer and wealthier residents.

Respondents reported increases in several mitigating behaviors: 53 percent reported staying home for 4+ days, and 90 percent reported both increased hand-washing and mask-wearing. While these numbers are encouraging, ensuring that people are actually following preventative measures at these self-reported rates—and doing so correctly and for a potentially longer period of time—remains an important policy priority. (On June 15, after the survey had concluded, the government made mask-wearing in public spaces mandatory.)

To better understand what role the social safety net can play in helping people abide by social distancing guidelines, IPA Ghana is currently evaluating how cash transfers affect social distancing compliance.

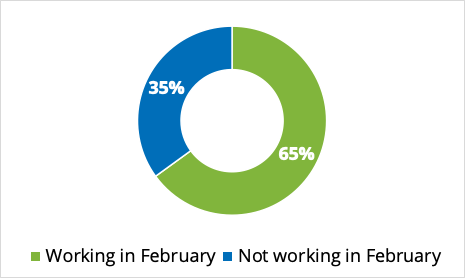

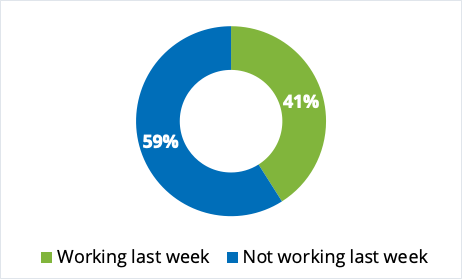

Many respondents stopped working, and those who kept their jobs worked and earned less.

Sixty-five percent of respondents reported that they had worked in February, shortly before the pandemic’s global impact became clear; surveyed in May, only 41 percent reported working in the last seven days. Overall, 21 percent of respondents reported that their business/place of work had closed.

Impacts on employment and earnings weren’t limited to those who lost their jobs. Of respondents who were still working, in the last seven days, nearly half (41 percent) reported earning less, and 29 percent had worked fewer hours than usual.

On May 19, a week before this survey round concluded, Ghana’s government announced that its Coronavirus Alleviation Programme would provide GHC 600 million (about USD$100 million) worth of loans for small and medium enterprises and aiming to reach 200,000 SMEs. A priority policy question for future survey rounds will be the extent to which the program is able to blunt the pandemic’s already-significant impact on work and income.

Impacts on employment

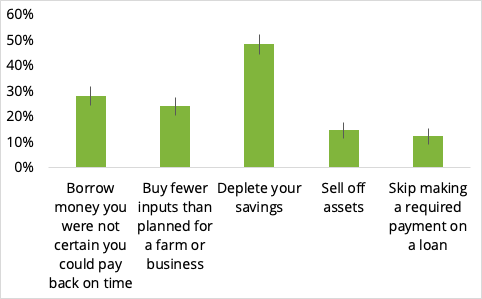

Households are strained financially, especially poorer ones.

Almost half of the respondents—48 percent—reported that they had depleted their savings to pay for food, healthcare, or other expenses since February. Twenty-eight percent had borrowed money they were not sure they could pay back on time, and 14 percent had sold off assets. Poorer households were more likely to report selling off assets to cover these expenses than richer ones. Twenty-nine percent of households, meanwhile, say they wouldn't be able to come up with 500 Cedis (about USD$200 PPP) within a month (with a higher proportion of women, 35 percent, reporting as much). With so many households selling assets and drawing down savings, that number could increase, increasing financial vulnerability even among those whose immediate household welfare was unaffected.

These numbers are startlingly high, and emphasize how, even if much of the crisis is temporary, a widespread economic shock can have long-term implications for households’ financial security.

How households are coping financially

The economic fallout of COVID-19 is already having sharp, adverse effects on respondents’ food security.

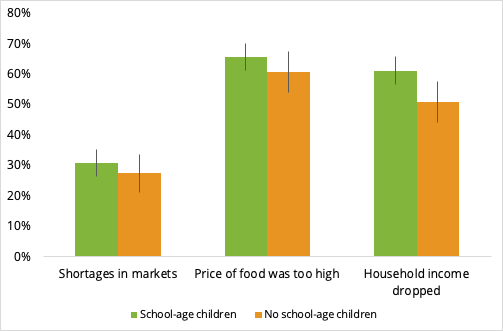

More than 40 percent of respondents said they had had to limit their portion sizes or reduce the number of meals they ate in the last week. A majority of respondents reported that losses in income had prevented them from buying food—57 percent—and 64 percent reported that the price of food was too high. Meanwhile, 29 percent reported shortages in markets that prevented them from buying food.

Households with school-age children were slightly more likely to report an inability to buy food because of a drop in income. This coincides with children losing access to school meals since schools have closed. Recent research in Ghana has found that even transitory spells of household food insecurity have significant impacts on early childhood development.

What led to a household's inability to buy food?

Given that many households have spent down savings or sold off assets, these impacts have the potential to worsen as time goes on.

In the meantime, small minorities of survey respondents reported receiving social safety net support from the government—2.8 percent reported receiving food or cash aid, while 14 percent reported getting free water or electricity.

Given that water bill collection was suspended in Ghana from April 1 to June 30, the number of respondents reporting that they had received free water is surprisingly low, suggesting that the suspension of water bills as a social protection policy may not be reaching beneficiaries at the levels it is intended to.

One possibility is that respondents were unaware of the benefit, and policies to increase awareness and take-up of these subsidies may be needed. Another, raised by the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration’s Charles Amoatey, is that wealthier Ghanaians who pay for their own water connections may be benefitting, but that poorer citizens tend to get water from a privately-owned community tap, and the owners of these taps may still be charging for access despite having their own water bills suspended. (A recent article from Devex sheds light on some more complicating factors of Ghana’s WASH sector).

A majority of children are spending some time on education at home, but households are concerned it's not enough.

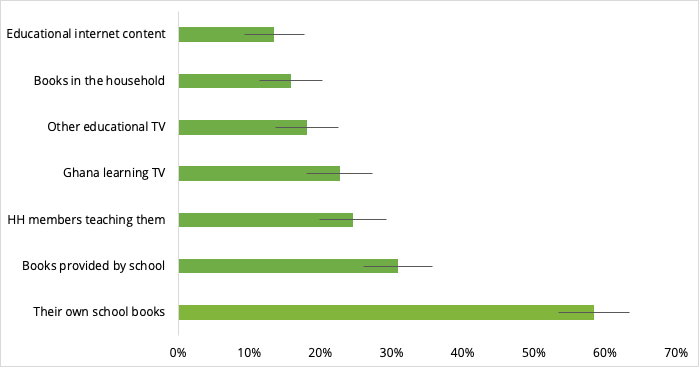

Respondents reported that a majority of pupils (64 percent of primary and 57 percent of secondary school children) are spending at least some time on education at home while schools are closed. However, children are spending an average of 5.9 hours per week on education—far less than they do in school. Wealthier and poorer children are spending comparable amounts of time on education. A majority of children (60 percent) are using their own school books to study at home, with smaller proportions studying with the help of household members, educational television, books in the household, or the internet.

How are children learning?

Only 32 percent of households reported receiving communication from their child’s school. Most parents reported being concerned about their school-aged children, with a large majority—60 percent—saying that their biggest concern is their children falling behind in education. The main reasons parents reported for children not spending time on education are a lack of supervision from adults in the household, lack of support from teachers and schools, and a lack of motivation in children themselves. Policy interventions to improve education could focus on expanded access to internet connections and distance learning platforms, as well as curriculum plans to prevent students from falling behind when in-person schooling eventually resumes.

What’s next?

These findings represent a snapshot of COVID-19’s socioeconomic impacts in Ghana during May 2020, soon after the Ghanaian government began easing its restrictions but before the bulk of the Coronavirus Alleviation Programme had begun. In the coming weeks, we will be discussing the findings and potential policy and programming implications with our goernment partners in Ghana, including:

- School meals are a demonstrated way to improve learning and nutrition outcomes, especially for the most vulnerable groups such as girls and the poorest children, especially in times of crisis. Food ration programs focused on families with young children, or the reinstatement of school feeding programs before school instruction resumes, could help to mitigate these adverse impacts.

- As students and teachers begin to return to school, remedial education programming such as STARS, the targeted instruction model already proven effective in Ghana and part of next year’s GALOP World Bank investment, could facilitate recovery of learning losses experienced during the COVID-19 distance learning phase.

- Ghana's emergency initiatives could be further strengthened by infusing more cash assistance as many neighboring countries have done. Such additional support can provide timely and necessary lifelines for the most affected households, such as daily laborers or agricultural workers who might have lost their sources of income completely due to the lockdowns.

With lasting uncertainty around the pandemic’s health and economic impacts, future survey rounds will shed light on priority policy questions from our partners as some activity resumes and the alleviation program continues. In the meantime, we will also soon be sharing takeaways from the RECOVR survey’s eight other countries.

Editor's note: this post was updated on July 14, 2020.