Digital Credit and Donor Funds: Public Goods for Private Companies?

Digital credit has transformed access to finance for hundreds of millions of consumers across the world. Through this innovation in loan delivery—characterized as “instant, automated, and remote”—people can now get loans over their phones in mere minutes. This has expanded financial access in ways never previously possible but has also led to concerns regarding aggressive marketing, high prices, and consumer risks of debt stress, such as in IPA’s recent analysis of digital credit transaction data in Kenya.

Given the potential to expand access to formal financial services digital credit promised—and achieved—financial inclusion donors provided considerable support to the industry’s growth, especially in Africa. While some donor support of digital credit has focused on research into the impacts of digital credit on borrowers, or policies to address consumer protection risks of digital credit, donor funds have also supported lender operations through tools such as loan loss guarantees for new digital credit products or paying for marketing campaigns to promote these products. As CGAP research shows, in many cases, development funders provided support to larger institutions like banks or MNOs, which are generally well-resourced, mature, and already profitable, so could probably finance these costs themselves.

Two recent areas of research raise important questions about how development funds (especially grant funds) should—or perhaps should not—be used to support private sector actors going forward. From my perspective, I worry that the financial inclusion community provided funds which subsidized the operating costs of digital lenders who have gone on to profit while underfunding investment in things like consumer protection supervision or market infrastructure like credit information systems.

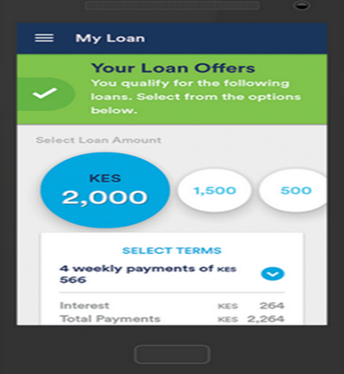

Screenshot from a borrower in Kenya using a digital loan product.

The first area of research comes from three recent digital credit impact evaluations in Kenya, Malawi, and Nigeria. In Kenya, Suri et al studied the impact of the M-Shwari digital loan product and found that of those who just qualified for M-Shwari loans, 62% report foregoing expenditures due to an unanticipated expense, versus 68% of those who just don’t qualify for the loan. Qualifying borrowers also reported positive expenditures on education at 83%, compared to 77% for those who did not qualify for a loan. The study did not find significant impacts on business and other expenditures. The authors conclude that “while digital loans improve financial access and resilience, they are not a panacea for greater credit market failures.”

In Malawi, Brailovskaya et al found higher self-reported financial satisfaction from those who took up the Kuchova digital credit product than those who did not. The researchers also tested interventions to increase understanding of Kuchova’s terms and conditions, which increased financial knowledge on fees and penalties. Interestingly, improving knowledge of fees actually increased demand for these loans and reduced late payment penalties, showing that transparency can be beneficial to providers not just consumers.

Most recently, Blumenstock, et al found that for borrowers from a digital lender in Nigeria, “increase in access to digital loans improves subjective well-being, but does not significantly impact other measures of welfare. The study rules out large short-term impacts—both positive and negative—on income and expenditures, resilience, and women’s economic empowerment."

These impact evaluations point to modest but generally positive effects of digital credit, more than transformative impacts on economic development or business expansion. This seems reasonable given these are often small balance, short-term loans. These studies also point to the little ways in which digital credit is expanding financial access and addressing the day-to-day needs of some households.

Going forward, donors should shift away from any further funding which supports lenders’ operations. A more useful investment could be to focus more on consumer protection and other market-level issues such as competition and consumer data rights.

The second area of research I want to highlight is the allocation of development funds across Fintechs. In June 2021, Silvia Baur-Yazbeck of CGAP authored Development Funders and Inclusive Fintechs: Analyzing One Decade of Funding Flows. Two findings from this research caught my attention as they relate to donor engagement on digital credit:

- “Development funders are growing their Fintech portfolios, but it is not clear if their funding reaches Fintechs and markets that lack access to capital from commercial investors. Early-stage, inclusive Fintechs receive capital from many sources, and development funders play a relatively small role.”

- 68% of development funding for FinTechs went to credit and payments Fintechs. “Less proven business models, such as for inclusive insurance and savings products, may benefit from grants to experiment and pilot. More mature Fintechs and credit Fintechs, in particular, may benefit from higher-stake and longer-term investments that allow funders to influence their business practices, ex., responsible lending.”

Baur-Yazbeck’s findings suggest that during the boom in donor engagement in digital credit, development funders may not have been supporting lenders who most needed financial support. Combining these findings with the relatively limited impact of digital credit on borrower welfare, I am concerned that development funder support in digital credit may not have been highly impactful given the limited impact of digital credit on borrowers and the concentration of funding which went to larger financial institutions.

Going forward, donors should shift away from any further funding which supports lenders’ operations. A more useful investment could be to focus more on consumer protection and other market-level issues such as competition and consumer data rights, which are not areas individual providers would likely invest in on their own, and which can have benefits for the entire industry and its customer base, instead of a single, often well-established financial service provider.

Philanthropic funds are limited and essential tools to combat issues in financial inclusion, health, education, economic development and so many other areas of need. Based on what we are learning through impact evaluations and analysis of donor funding trends, the story of development funding of digital lenders in the past decade should give us all pause when the next innovation comes around. Instead of funding private firms’ operations, it may be better for early development funder activity to support research like impact evaluations of these new innovations, and a policy environment that evolves alongside the industry to safeguard consumer protection and competition in the long run. We need to be careful how development funds, especially grant funds, are used to subsidize private sector operations and, in turn, private-sector profits, often going primarily to the larger, more dominant actors in digital financial services.