Community Monitoring Intervention Improves Headteachers’ Response to Coronavirus Pandemic

What kinds of interventions could help improve schools’ and communities’ response to the coronavirus pandemic?

Research during the Ebola epidemic found that a community monitoring intervention in Sierra Leone was able to save lives when the epidemic hit, apparently through building confidence and trust in government health clinics. People were more likely to overcome fear and stigma and report to clinics for testing and treatment, which lowered death rates.

Could a similar intervention be useful for the education sector in the context of the coronavirus pandemic?

For the past seven years, the NGO Elevate: Partners for Education has been working to implement a community monitoring intervention in Ugandan primary schools. Elected representatives monitor issues at their school and communicate that information to education officials and community members. Elevate’s work builds on the result of a previous study, which found that this intervention improved student and teacher attendance, as well as students’ test scores.

As a technical adviser for Elevate, I’ve been supporting their work for six years as they implement the intervention and conduct additional research.1 Last year, we completed an impact assessment. We didn’t observe the same impacts as the prior research but did find that Elevate’s implementation decreased student dropout and transfer rates. Learning from this experience, Elevate started redesigning their implementation model and testing it in new schools.

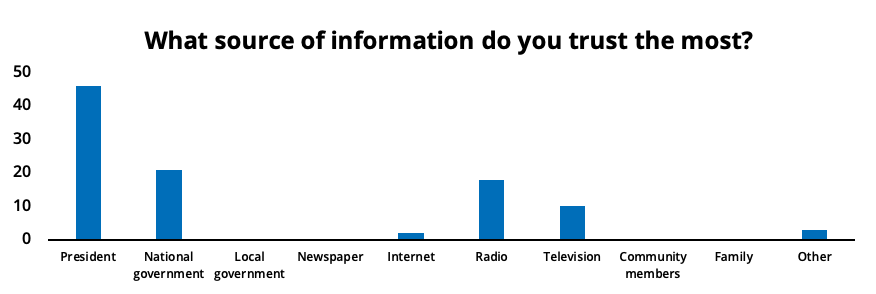

Then on March 18, 2020, Uganda’s President Museveni ordered all schools to close in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Elevate quickly started looking into ways to support schools and share information with other educational actors. Between May and June of this year, we conducted a phone survey of headteachers who had participated in the impact assessment. Ultimately we were able to contact 88 of the 100 headteachers of the Ugandan government primary schools in our study.

Headteachers’ understanding of the coronavirus is mixed

To get more context about how school leaders understood and were responding to the virus, including their likelihood to follow health guidelines, we asked some basic questions about their understanding of the virus. When asked how they would explain the coronavirus to a member of their community, several headteachers responded by saying things like, “Flu-like virus that is tougher than the ordinary flu” and “It's a disease outbreak that spreads very fast and is more serious than ordinary flu.” When asked, do you think anyone is at fault for the situation caused by the coronavirus, 57% of headteachers responded that "No one is at fault, viruses are a part of life," and 15% said Dubai, reflecting the fact that Uganda’s first cases of the coronavirus were observed in travelers who had been to Dubai. Of the 88 headteachers we surveyed, 3 responded to the question, "Do you think anyone is at fault for the situation caused by the coronavirus?" by saying, “The people who created coronavirus in the labs.”

When asked, "Is your school doing anything to encourage children’s learning while schools are closed?" 28 percent said that their school was not doing anything. Out of the 72 percent that were, 85 percent said that they told students to look over their schoolbooks and 41 percent said that they gave students worksheets and materials. Only 3 of the 88 headteachers reported that their schools’ teachers were in communication with students. Interestingly, these three headteachers were all in schools that participated in Elevate’s community monitoring intervention. With such a small sample size, though, that might just be due to chance.

Impact of community monitoring intervention on headteachers’ response

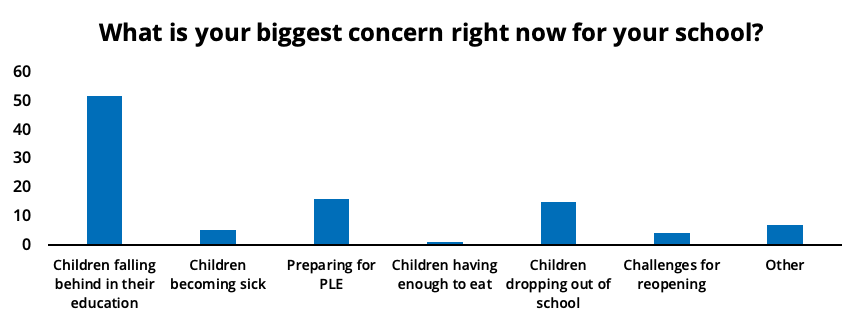

For several questions on our phone survey, we compared the responses of headteachers in schools that received Elevate’s community monitoring intervention with those that did not. This comparison provides a promising indication that the intervention shaped the way that headteachers are responding to the pandemic.

In response to the question, "What is your biggest concern for your school right now?" headteachers in schools that did not receive Elevate’s community monitoring intervention were four times more likely to say “Children dropping out of school during this period” than headteachers in schools that did participate in Elevate’s program. This aligns with our study’s finding that the community monitoring intervention decreased school dropout. More than a year after our study concluded, headteachers still seem to be influenced by the intervention’s effects and are less concerned about school dropout.

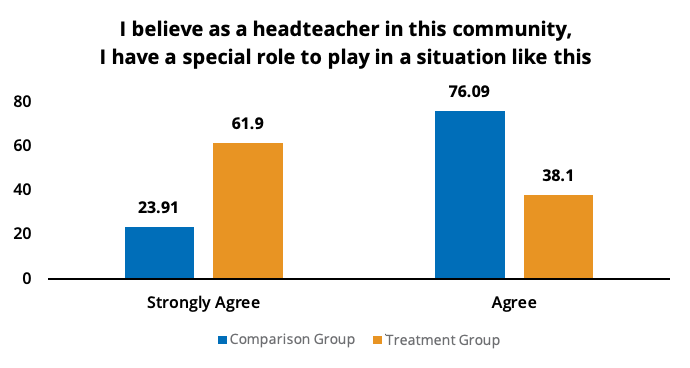

We also read headteachers a series of statements and asked them to what extent they agreed or disagreed with each statement. In response to “People in this community do not trust teachers,” headteachers with community monitoring were four times more likely to strongly disagree, suggesting that they perceive more trust in teachers in their communities.

Headteachers in treatment schools were also 1.7 times more likely to strongly agree with the statement, "I believe as a headteacher in this community I have a special role to play in a situation like this." It’s possible that Elevate’s intervention may have empowered headteachers to take meaningful action during this time.

While the study only captures self-reported attitudes and behavior of headteachers, the suggestion that a community monitoring intervention increased trust and school response to a pandemic a year later is encouraging.

Once schools reopen it will be especially important for different stakeholders to work together. Our research in Uganda found that even under normal circumstances, teachers often place blame on parents and parents will often blame teachers. Elevate’s community monitoring intervention got school level stakeholders to move away from finger-pointing and towards collaboration, which will be needed in the coming months.

To learn more, read this interview in which Elevate’s Emmanuel Odeke and Christine Nagawa reflect on their work conducting this survey.

1 This work took place before my current position with IPA.