Closing the Learning Gap: Building Liberia's First National Primary Learning Assessment System

By Arja Dayal, Joe Gbasakollie, Madia Herring, Andreas Holzinger, Mark Jäger, Walker Higgins

Editor’s Note: In Liberia, IPA worked with the Ministry of Education to prepare for education reform in the country by developing learning assessments to help the Ministry measure to what extent children are learning and how their new programs are working. IPA partnered with the MoE to develop the first National Learning Assessment System (Policy and Framework) for primary grades, testing different possible assessment tools in a pilot study. Findings show a written assessment model that is group-administered in Grade 3 and self-administered in Grade 6 to be a recommendable and cost-effective solution for the Liberian context.

Here, Joe Gbasakollie and Madia Herring from Liberia’s Ministry of Education, and Mark Jäger, Andreas Holzinger, Walker Higgins, and Arja Dayal from IPA walk us through how they worked together.

The significant role human capital plays in explaining income differences across countries highlights the urgency for investments in improving education quality and learning outcomes. However, global progress in learning over the past two decades, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, has been limited. While an estimated 88 percent of primary and lower secondary school-age children in sub-Saharan Africa are not achieving minimum proficiency in reading, the unfortunate truth is that in many countries we do not even know how bad the problem is because we do not have a standard way of measuring it. To improve learning, countries need to know how individual students are doing, how schools are doing, and how they are doing compared to peer countries, so there has been a general trend in sub-Saharan Africa towards establishing national learning assessment tools.

Liberia is transitioning from a content-based (memorization and repeating back) to a competency-based (mastering skills) curriculum that places learning as the central priority of its education system. Liberia does currently have a national Primary School Certificate assessment, given every year to Grade 6 students, but it has limits. A new standardized assessment should measure what learners understand—not just what they can memorize—and be versatile enough to assess a wide range of students wherever they are on the learning spectrum.

How do you work together to develop a new national assessment system?

IPA has partnered with the Liberian Ministry of Education (MOE) to develop Liberia’s first National Learning Assessment System (NLAS) for primary grades. Along with our colleagues Aditi Bhowmick, Alejandro Ganimian, and Sarah Kabay, we developed assessments and then piloted them to see if they worked as designed to accurately measure student learning levels. The general purpose of the NLAS is two-fold: First, it is important for Liberia to know how their students perform in both national and international comparison to pinpoint specific areas where learners are not performing as well as they should. Second, as the Liberian government reforms its curriculum, it needs to know early on whether adjustments bear fruit, or what to do differently. These insights are particularly useful when comparing different samples of students across school types, location, genders, etc. For the long-term success of the system, institutionalizing assessment procedures within the MOE is key, and IPA has partnered with the MOE from the start to ensure the tools we develop together will continue to be sustainably used.

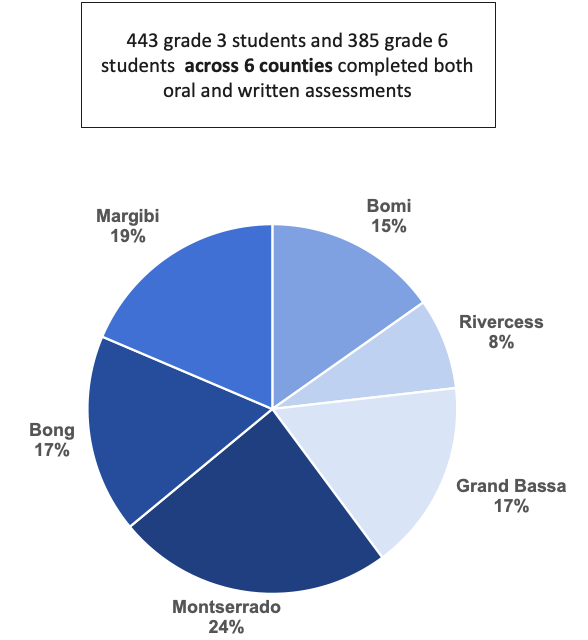

874 students reached despite COVID-19 and first assessment piloting across counties

In the piloting exercise, we gave the same students an oral (administered by an adult individually to each student) and a different written version of the assessment to see which would work better. Oral assessments have the advantage of being accessible to students with reading difficulty and can also measure reading fluency, while written ones can more easily reach larger numbers of students and allow for an increased variety of questions and skills to be tested.

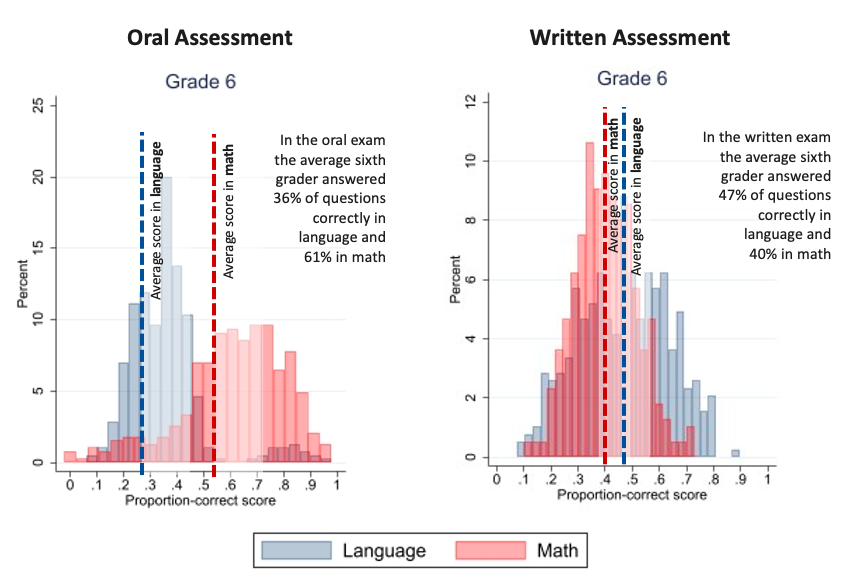

For the test to be properly calibrated to the students, there should be a healthy distribution of scores—large numbers of students at the bottom (“floor effect”) would indicate the test was too difficult, and correspondingly a “ceiling effect” where all the students score at the top of the range would indicate it was too easy. The final outcome of the pilot was promising: Both oral and written showed full distributions, though the oral test showed slight signs of ceiling effects with 6th-grade students. The written assessment, which covered a broader range of competencies, cognitive domains, and levels of difficulties, appeared to cover the full distribution well.

Both oral and written assessments show full distributions, although the written assessments captured variance among learners more effectively.

The results from the pilot showed:

- Over 90 percent of pupils in the pilot were over-age for their grade, most of them substantially, which confirms students shouldn’t be selected by age for the assessment.

- Because of the wider range of questions possible and healthier distribution of results, we recommend the written assessment, which also has the advantage of being cheaper and easier to administer as the government seeks to roll it out more broadly by possibly leveraging the existing system of the West African Examinations Council (WAEC).

- Considering that written assessments do not allow us to check how many words per minute students can read fluently (oral fluency benchmark), the proposed assessment policy encourages existing efforts continue to use complementary oral assessments.

- Given the high variance in reading ability among learners in lower grades, a group-administered approach for the written assessments is more suitable for 3rd-grade students, who might need more assistance, while a self-administered model is likely appropriate for 6th-grade students.

- For standardized tests to work, assessments need to be administered in a secure and standardized way, data collection has to be precise and uniform, scoring accurate, and school officials have to be engaged in the process. We suggest that rather than a widespread roll-out, the ministry phases it in with an emphasis on the ability of local education authorities to administer it.

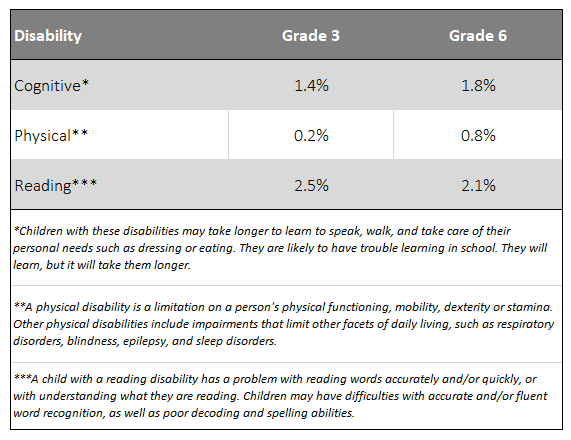

- Teachers identified different forms of disability among sampled students from Grades 3 and 6 in our pilot. The roll-out plan should aim to meaningfully adapt NLAS and include students with disabilities, out-of-school students, and those who speak non-English languages.

Outlook and way forward

Having students from different parts of the country sitting for the same assessment, administered with the same instructions and circumstances, answering questions applicable to students in the same grade with a wide range of ages and skill levels, with data collected and scored precisely and identically is not a simple task, but it is a necessary one to know how each child is doing, and where the educational system as a whole stands. As we learned from our piloting and adjustment, it is also a process that requires monitoring, flexibility, and willingness to adjust. We think a successful implementation of the NLAS is the first step towards developing the data that Liberia will need to achieve its education goals and contributing to building the long-term human capital of the country. We look forward to continued collaboration with the Ministry as they develop the system further.

This project was made possible due to the generous funding and support from the Global Partnership for Education.

The Liberian Ministry of Education's National Learning Assessment System team with IPA staff during a COVID-19 safe field staff training.

Blog Authors:

Joe Gbasakollie is a Project Coordinator in Liberia’s Ministry of Education.

Madia Herring is Director of the Center of Excellence for Curriculum and Textbooks Research in Liberia’s Ministry of Education.

Arja Dayal is a consultant and former Country Director for IPA’s Sierra Leone and Liberia offices.

Andreas Holzinger is the current Country Director for IPA’s Francophone West Africa offices and former Country Director of IPA’s Sierra Leone and Liberia offices.

Mark Jäger is a student volunteer with IPA’s Sierra Leone and Liberia offices.

Walker Higgins is Country Manager for IPA’s Sierra Leone and Liberia offices.