61,000 Parents Share How School and ECD Center Closings Take a Toll on Their Mental Health

By Juan Manuel Hernández-Agramonte, Guisselle Alpizar, María Loreto Biehl, Laura Ochoa Foschini, Olga Namen, Emma Näslund-Hadley, and Brunilda Peña de Osorio 1

Editor's note: This is a cross-post of a blog that originally appeared on IDB's blog page in English and Spanish.

With the sudden halt to face-to-face education, parents across the world juggle distance and hybrid education models. In addition to being parents and often full-time employees, overnight they suddenly also became full-time educators and classroom managers. The additional burden on parents comes at the cost of decreased mental health.

In Latin America, the ministries of education in El Salvador (MINED) and Costa Rica (MEP) and the institute of family wellbeing in Colombia (ICBF) joined forces with Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to explore parents’ experiences of emergency distance education. Beyond information about the functionalities of online learning platforms and phone-based support, the survey of more than 61,000 parents paints a picture of a mental health toll on parents who scramble with distance and hybrid education in addition to other challenges of the pandemic. Some 85% of caregivers in the survey report at least one symptom of distress, calculated based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-R).

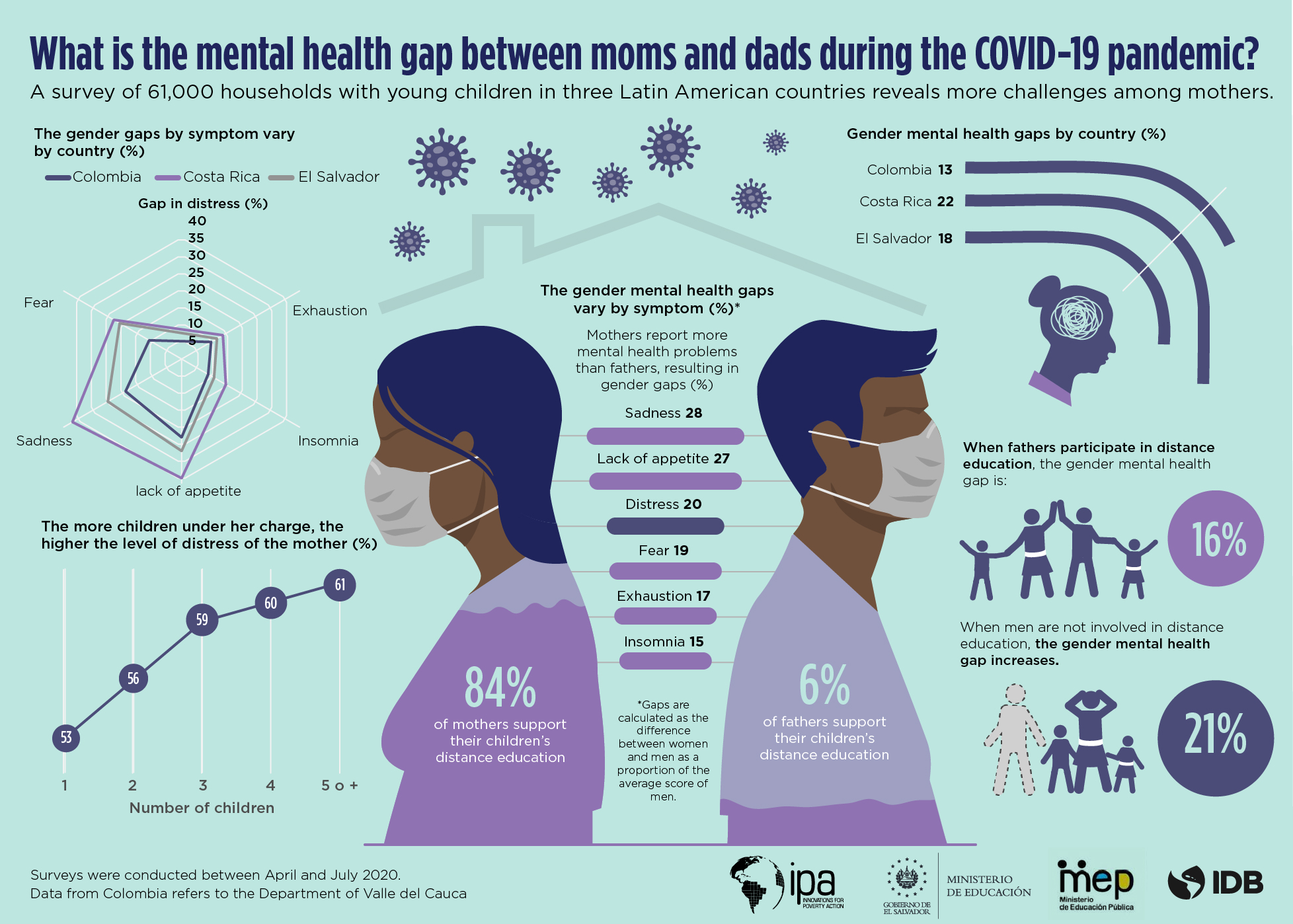

Although the mental health of all age groups takes a toll during the current pandemic, mothers with young children appear to be particularly affected. This group shoulders the burden of distance education, while often caring for infants and toddlers. We find that 84% of mothers of young children are involved in their children’s distance education, compared with only 6% of fathers.

The survey data suggests that additional responsibilities with no signs of relief appear to negatively affect the wellbeing of mothers. Women who are the main breadwinners report higher levels of overall distress compared with other women with young children. Similarly, the more children a woman has the higher her overall level of distress, progressively increasing from 53% in one-child households to 61% in five-child households. Economic stressors, including loss of employment and reduction in income, also increase the distress of women. For example, in Colombia, the level of stress of women is 13% higher in households with job or income losses due to the pandemic compared with women in other households.

The infographic was designed by Juan Manuel Hernández-Agramonte, winner of the visualization on inequity contest from the IDB.

Mothers report more mental health problems than fathers, resulting in vexing gender mental health gaps in sadness (28%), lack of appetite (27%), overall distress (24%), fear (19%), exhaustion (17%), and insomnia (15%). Costa Rica has the largest gender gaps in mental health, including differences of 35 and 37% in lack of appetite and exhaustion. The overall mental health increases from 16 to 21% when fathers are not involved in the distance education of their children.

It is essential to support mothers in this challenging time, not just to decrease their stressors, but to avoid their distress trickling down to the next generation. Previous international research reveals that parental stress has long-term implications for children’s brain development. What steps can be taken to mitigate stressors and promote the social, emotional, and mental health of parents? How do we involve fathers in their children’s distance education? Share your comments with us in the section below, or comment on Twitter.

1. We thank Kelly Montaño, Rayssa Ruiz, and Carlos Urrutia from IPA for their excellent research assistance; and Ekizache Foxua for the graphic design.