Free Malaria Bednets

Abstract

Governments and organizations have reconsidered their policies to charge for bednets in recent years in response to evidence that even small fees reduce coverage.

In 2007, IPA affiliates Jessica Cohen and Pascaline Dupas conducted a study showing that in rural Kenya, charging even small prices to pregnant women for insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) significantly reduced coverage. In 2009, the British government cited the study in calling for the abolition of user fees for health products and services in poor countries. Other governments and many organizations have also reconsidered their policies to charge for health services in recent years, opting instead to distribute insecticide treated nets (ITNs) and other health products free of charge.

The Challenge

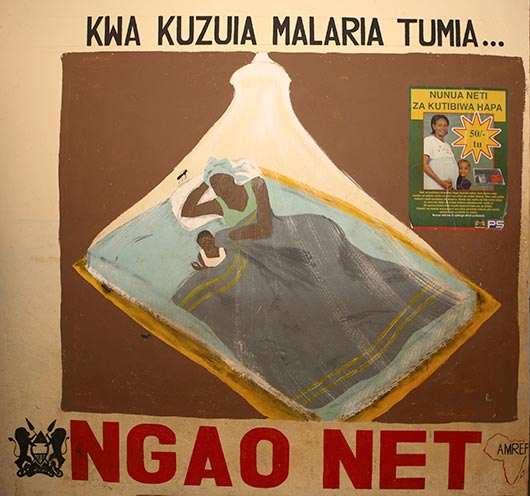

In 2015, there were 214 million cases of malaria, and 438,000 people died from the disease, according to the World Health Organization. The majority of these deaths were in sub-Saharan Africa, which is home to an estimated 90 percent of the world’s malaria cases.1 Public health experts and officials have long agreed that prevention through widespread use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs or bednets) is the most viable way to prevent and control malaria. Yet ITN coverage is woefully low among the most vulnerable groups, such as pregnant women and children.

There is a general consensus among academics and policymakers that the provision of public health goods that benefit not just the individual but the whole community should be subsidized or even free. But there is also a long-running debate on what proportion of the cost the beneficiaries of these public health programs should bear. For years, many practitioners have argued that charging even a nominal fee for health products is better than giving products away for free. They argue that a small cost screens out those who do not value the good (enhancing the likelihood funds are spent on products that people actually use), and also that charging fees may help raise revenue to make programs more financially viable, and therefore, sustainable. However, others argue that charging for these products reduces the number of people who ultimately receive and use them, with negative health consequences for the whole community.

The Evidence

Since its creation in 2003, Together Against Malaria (TAMTAM) has delivered free ITNs through prenatal clinics to increase coverage among pregnant women and children.2 As of 2007, another common approach, most prominently promoted by Population Services International (PSI), provided ITNs at subsidized prices throughout the African continent. To test whether it is preferable to freely distribute bednets or require a co-payment by recipients, in 2006 Jessica Cohen and Pascaline Dupas, founders of TAMTAM, put their approach to a rigorous test. In 16 randomly selected health clinics, ITNs were distributed at a subsidized rate, with the discount varying between 90-100 percent of market price. Researchers found that charging even small prices for the nets considerably decreased demand: ITN take-up dropped by 60 percentage points when the price increased from zero to $0.60 (i.e. from 100 to 90 percent subsidy). Furthermore, women who received ITNs for free were just as likely to use the ITNs as those who had paid for it. The combination of lower uptake at positive prices and no change in the usage rate translates into lower absolute number of ITNs in use. For more, see the related study page and the cost-effectiveness brief.

The Impact

In the past few years, many organizations have reconsidered their policies to charge for health services, opting instead to distribute ITNs and other health products free of charge. The elimination of user fees is now strongly supported by a number of influential organizations including the U.K.’s Department for International Development (DFID), Save the Children UK, the United Nations Millennium Project, and the Commission for Africa.3 In 2009, the British government cited the study by Cohen and Dupas, alongside Kremer and Miguel’s study on the effect of cost-sharing on deworming take-up, in calling for the abolition of user fees for health products and services in poor countries. Many countries including Burundi, Nepal, Malawi, Zambia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, and Liberia are responding to this call, taking major steps towards the provision of free services.4

Population Services International (PSI) is a leader in malaria prevention, providing malaria control support to national Ministries of Health in over 30 countries worldwide. Traditionally PSI has supported the practice of cost-sharing for ITNs as they believed that positive prices increase usage and promote sustainability.5 PSI has increasingly moved to free distribution of ITNs for pregnant women. Today, PSI’s bednet delivery strategies include routine facility-based delivery, mass free distribution for rapid scale-up and continued engagement of the private sector in some locations. For example, in Kenya PSI delivers free ITNs to pregnant women through 3,000 public antenatal clinics, while at the same time subsidizing ITNs sold commercially.6 The World Bank has also started shifting away from the social marketing position, and the WHO also endorses free distribution of bednets.7

If you know of other organizations that are using these results, or have any corrections or updates to make to this case study, please contact comms@poverty-action.org.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Sources

1 AMREF, “Malaria,” available online at http://www.amref.org/what-we-do/fight-disease/malaria/.

2 Together Against Malaria (TAM TAM), “Overcoming the Burden of Malaria: Perspectives from the Frontline,” March 2005, available online at http://www.tamtamafrica.org/docs/TAMTAM_Research.pdf

3 Eldis, “Abolition of User Fees” (service provided by, The Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, funded in part by DFID), available online at http://www.eldis.org/go/topics/dossiers/meeting-the-health-related-needs....

4 “PM’s article on universal healthcare,” Number10.gov.uk \- The Official Site of the Prime Minister’s Office, Sept. 23, 2009

5 PSI (2006), “What is social marketing?,” available online at http://www.psi.org/sites/default/files/publication_files/what_is_smEN.pdf

6 PSI, “Malaria Prevention and Treatment,” available online at http://www.psi.org/our-work/healthy-lives/malaria/about/prevention-and-t....

7 Sachs, Jeffrey D. (2005), The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time, Penguin Press.

Lancet (2007), “Science at WHO and UNICEF: The Corrosion of Trust,” Lancet, Editorial, 370: 1007. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(07)61451-2/fulltext

WHO (2007), “WHO releases new guidance on insecticide-treated mosquito nets,” World Health Organization News Release, August 16, 2007,http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2007/pr43/en/index.html