Cash Transfers: Changing the Debate on Giving Cash to People Living in Poverty

Abstract

The evidence on cash transfers, and the publicity around their success, has changed the way we think about giving cash to people living in poverty and created a standard of comparison for other programs. It has also spurred donors to dedicate millions more dollars to unconditional cash transfer programs.

Until recently, giving large amounts of cash directly to people living in poverty was met with great skepticism. Yet the impact of administering cash transfers to the extreme poor had yet to be measured. IPA-affiliated researchers have now produced a body of evidence that shows cash transfers can substantially improve the lives of the extreme poor. The evidence, and the ensuing publicity around cash transfers, has changed the way we think about giving cash to people living in poverty, creating a valuable benchmark against which to evaluate other programs. The evidence has also helped the main organization that administers unconditional cash transfers, GiveDirectly, raise substantial funds to provide grants to more people living on less than $2 a day.

The Challenge

In 2014, the U.S. government spent roughly $24 billion on poverty-focused foreign assistance programs around the world—a huge investment (though still only 0.7 percent of the federal budget).1 For years, poverty alleviation programs have focused on delivering goods or services, building infrastructure, providing training, or more recently, providing financial services, like microloans. Conventional wisdom has told us that these programs are better than doling out cash. Starting in the early 2000s, however, governments started experimenting with providing people living in poverty with cash grants under conditions that they use the money in a certain way or follow through on a commitment, like sending their children to school. The success and relative affordability of these conditional cash transfer programs made them popular around the world, and many began asking if the “conditions” were necessary.

The Evidence

A body of evidence now shows both conditional and unconditional cash transfers can make substantial positive impacts on the lives of people living in poverty.2 Here are some examples:

One-time cash grants of $374 provided to young adults in conflict-affected northern Uganda had significant impacts on income and employment four years later, a study by Christopher Blattman, Nathan Fiala, and Sebastian Martinez found. Individuals who received the cash, through Uganda’s Youth Opportunities Program, had 41 percent higher income relative to a comparison group and were 65 percent more likely to practice a skilled trade. Women in particular benefited from the cash transfers, with incomes of those in the program 84 percent higher than women who were not. The grant was provided under the condition that recipients submit a business plan. Read more about that evaluation here.

Another conditional cash grant program for women only, implemented by AVSI in northern Uganda and evaluated by Jeannie Annan, Christopher Blattman, Eric Green, Christian Lehmann, and Julian Jamison, led to dramatic increases in business and reductions in poverty: In 18 months, the women started businesses, their incomes doubled, and they got a big boost in savings. Apart from cash, the recipients also received business skills training and mentoring. Read more about that evaluation here.

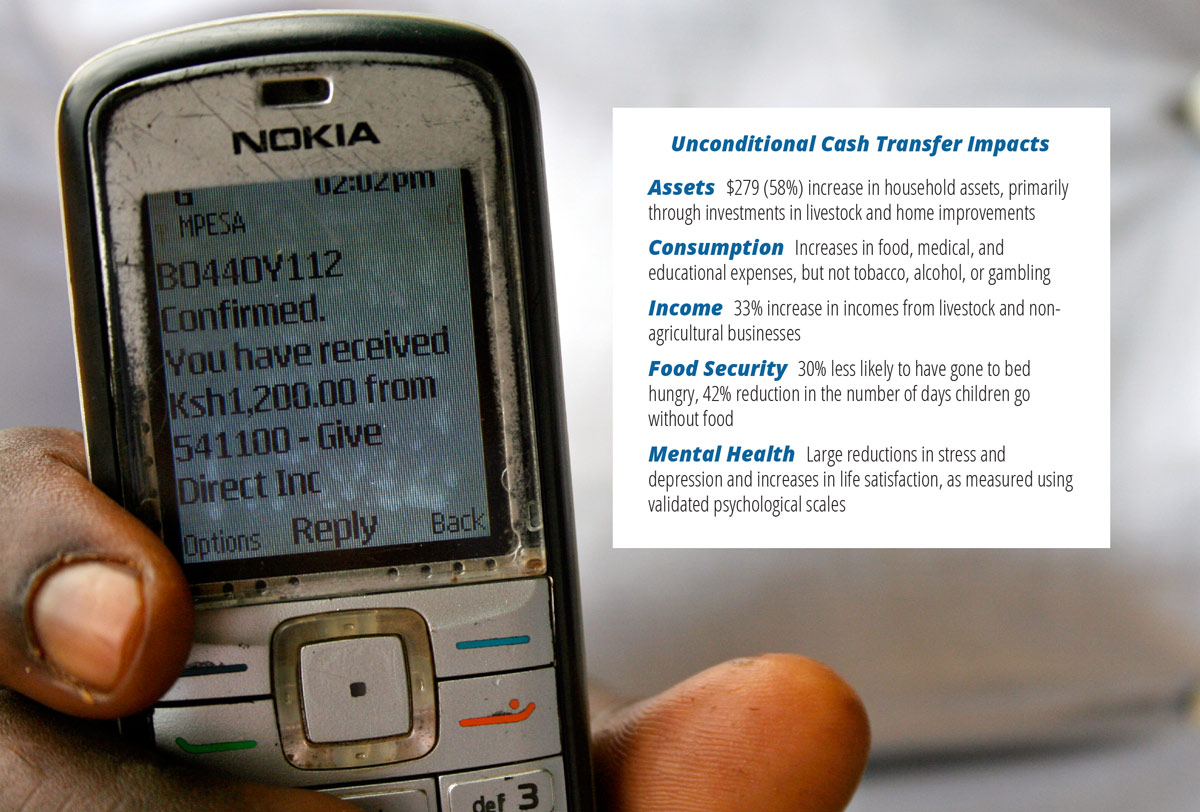

Then, in 2013, results came out that an unconditional cash transfer program in Kenya administered by GiveDirectly had a substantial impact on people living in poverty. The study, led by Johannes Haushofer and Jeremy Shapiro, found that simply providing people with cash (average amount US$513) and nothing else led to dramatic increases in income, assets, psychological well-being, food consumption, and female empowerment among the extreme poor. This evaluation was the first to show that providing cash alone can have large impacts on the lives of people living in poverty. Read more about that evaluation here.

The Impact

The studies on cash transfers, including those mentioned above, spurred a public discussion and an overall validation of direct giving as a cost-effective poverty-alleviation tool. Now, the direct transfers are serving as a standard of comparison for other programs. The evidence has also spurred donors to dedicate millions more dollars to unconditional cash transfer programs, reaching thousands more people living on less than $2 a day.

Changing the debate

Direct giving was once a radical idea, but the widespread media coverage on the research on cash transfers has changed that. The New York Times reported on the “profound effects” of the first Uganda study in 2013 and published a Q&A with Blattman. Slate called the transfers “an amazingly powerful tool for boosting incomes and promoting development.” The Atlantic called GiveDirectly’s program “genius,” while Bloomberg Businessweek called the transfers “surprisingly effective” and concluded: “So let’s abandon the huge welfare bureaucracy and just give money to those we should help out.”

In fact, the buzz around direct giving was so big, some cautioned that cash transfers are not a cure-all. Certainly, giving people cash is not a panacea, and as the Economist warned, it cannot address many of the deeper causes of poverty. However, what’s clear is that giving cash is an effective tool—even if it is just one tool in the toolbox.

Validation brings more funding

The evidence on unconditional cash transfer programs has spurred donors to dedicate millions of dollars to these programs. In 2015, Good Ventures gave $25 million to GiveDirectly, citing that it is cost-effective and evidence-backed, and that cash transfers have the potential to be “a tool for greater impact and accountability in international aid and development.” GiveDirectly plans to use $16-19 million to provide cash directly to people living in poverty and $6-9 million on building a fundraising and marketing team. The organization ultimately aims to scale the program globally.

A standard of comparison

Cash transfers are transforming the international development sector by creating a standard of comparison for other programs, potentially raising overall standards by injecting more competition into the sector.

IPA plans to be at the forefront of this trend, using unconditional cash transfers as a benchmark with which to evaluate other programs. We are currently developing several evaluations that ask something we probably should have been asking all long: “How does this intervention compare to just giving someone money?

If you know of other organizations that are using these results, or have any corrections or updates to make to this case study, please contact comms@poverty-action.org.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Sources

[1] https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/foreign-aid-101/

[2] Evidence suggests cash grants are not effective in every context. High-risk men in Liberia who received cash grants saw only short-lived gains. Read more about that study here.