Realities of Remote Learning: Lessons from Initial Findings of an 8,000-Household Survey in Peru During COVID-19

By Juan Manuel Hernández-Agramonte (IPA), Carolina Méndez (IDB), Olga Namen (IPA), Emma Näslund-Hadley (IDB), and Luciana Velarde (OSEE, Minedu)

Editor's note: This is a cross-post of a blog that originally appeared on IDB's blog page (in Spanish).

Most schools throughout Latin America have closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. With the school closures, nearly 8 million Peruvian students, from preschool to high school, are stuck at home. Within a few weeks, the Ministry of Education (Minedu) developed the Aprendo en Casa (AeC) (meaning “Learn at Home”) strategy. And on April 6, three weeks after the schools closed, 82 percent of households with children aged 3 to 4 years old started their morning accompanied by Elmo from Sesame Street, who explained why they should wash their hands. Other programs for the different grades of primary and secondary levels followed. That day, 4.3 million people watched educational programming. These television programs are complemented by activities on the AeC web platform and radio programs in nine indigenous languages.

Although the strategy has been designed with diverse users in mind, many have asked: How many students are actually using the AeC distance education program? What can we improve?

In this context, Minedu's Office of Strategic Monitoring and Evaluation (OSEE), with the support of Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), designed a survey to learn about the experiences of school administrators, teachers, and parents with the program. A first-round of telephone surveys included 4,303 principals, 5,328 teachers, and 8,319 parents (30 percent in rural areas and 70 percent in urban areas). The latter group is represented at the national level. However, due to the lower response rate in rural areas, the results from rural areas should be interpreted with caution.

The survey allows us to enter the ''black box'' of what happens within households with the distance education resources that have been made available during the pandemic. This will allow Minedu to adjust AeC to improve the service. This first post in a series of three discusses how families are experiencing the distance education program thus far, and some lessons learned.

Do families know that Minedu offers distance education resources? 91 percent of households are aware of the AeC, mainly through television (65 percent) and their teachers (46 percent). Less than 20 percent of households are aware of the radio program. Seventy-five percent of the families of bilingual intercultural school students know of AeC and 91 percent access its content.

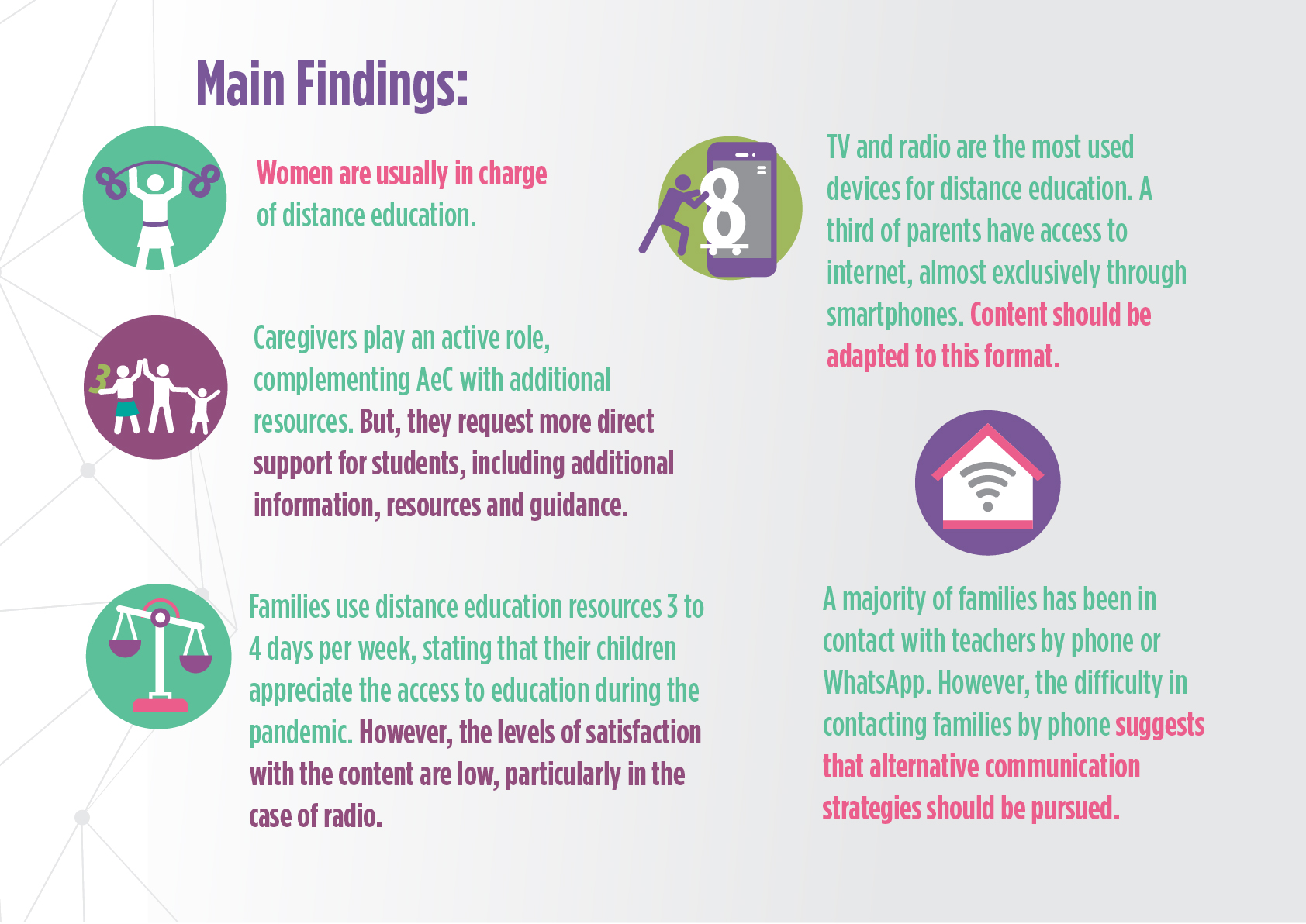

Who accompanies the student in distance education? In most cases, mothers support students’ at-home learning (67 percent).

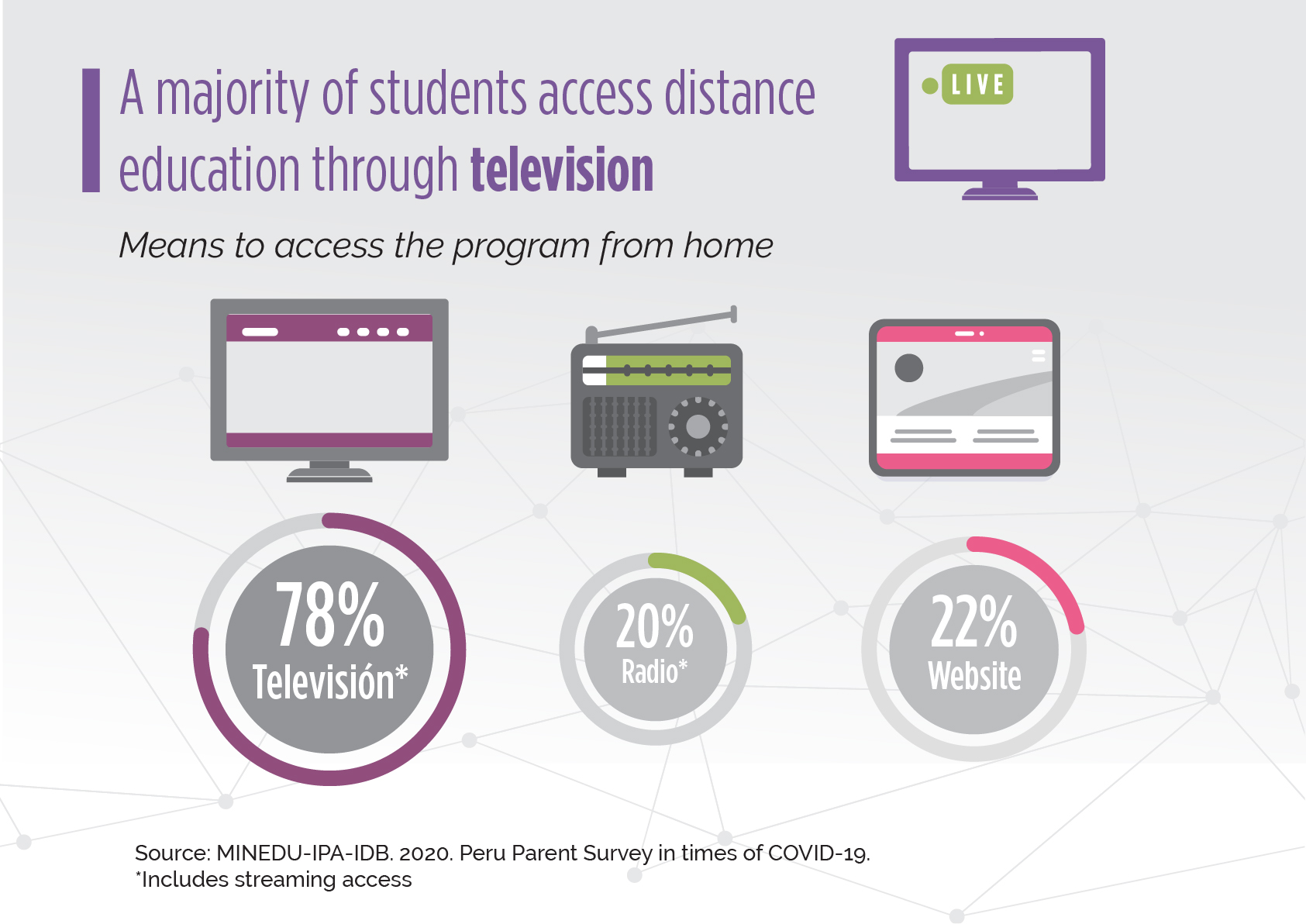

What devices do families use for distance education? The most common device is television (78 percent) and to a lesser extent radio (20 percent) or the internet (22 percent). 81 percent of households access AeC only through one device (television, radio, or internet), 18 percent access through two devices, and one percent through three devices.

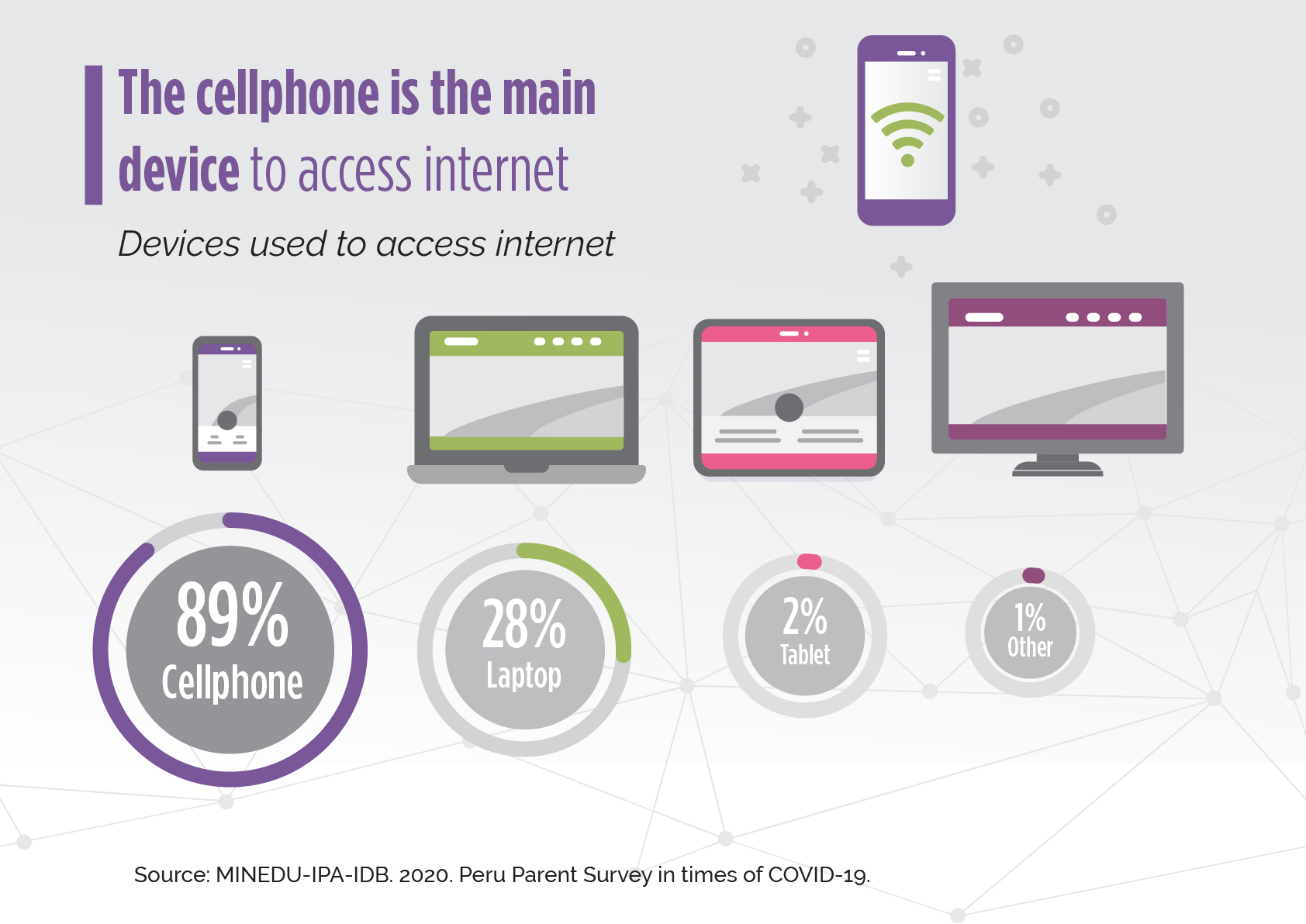

What are the implications of limited internet access? Limited internet access (39 percent) suggests the importance of designing content and methodologies for a cell phone screen, avoiding files for download.

Are parents satisfied with distance education? Parents report that students like the program (83 percent), and that distance education should continue next school year as a supplement to in-person education. However, parents also indicated the need to improve some aspects of the program—such as short class durations, a lack of interaction with teachers, and a general lack of information.

What other educational tools do parents use during COVID-19? Caregivers are taking an active role in their children’s education using additional educational resources (78 percent), including stories, schoolbooks, and drawings. This provides an opportunity to continue motivating and guiding parents to complement the homeschooling of their children.

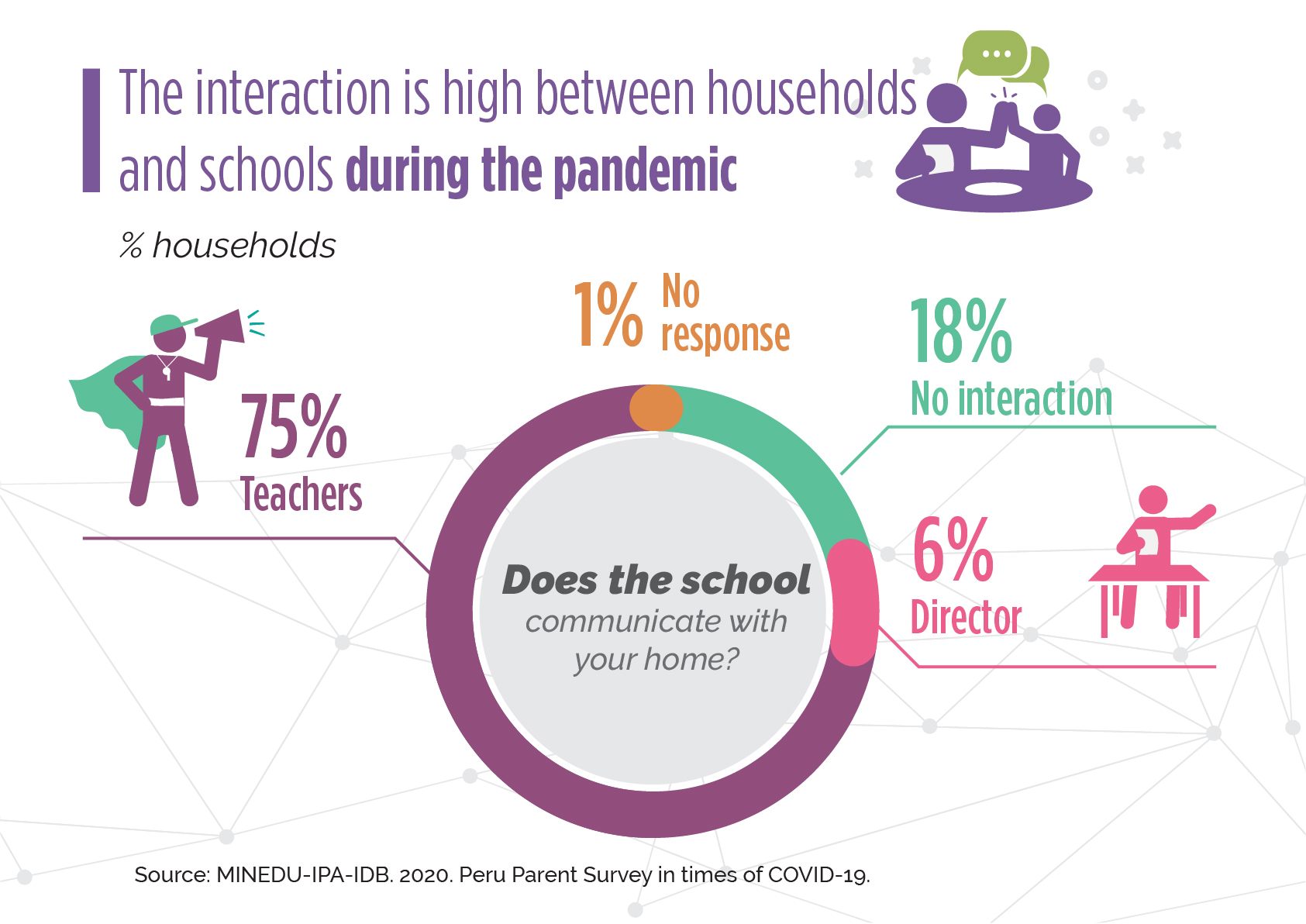

Are families in contact with their schools? The interaction between families and other actors in the educational community is high, 79 percent of families have maintained communication with the teacher, promoter, coordinator, or school principal. However, this conclusion is limited by access to cell phones, internet, and good cellphone coverage. The most used means of communication are cell phones and WhatsApp calls. Topics covered include information about AeC, and teacher support in and learning.

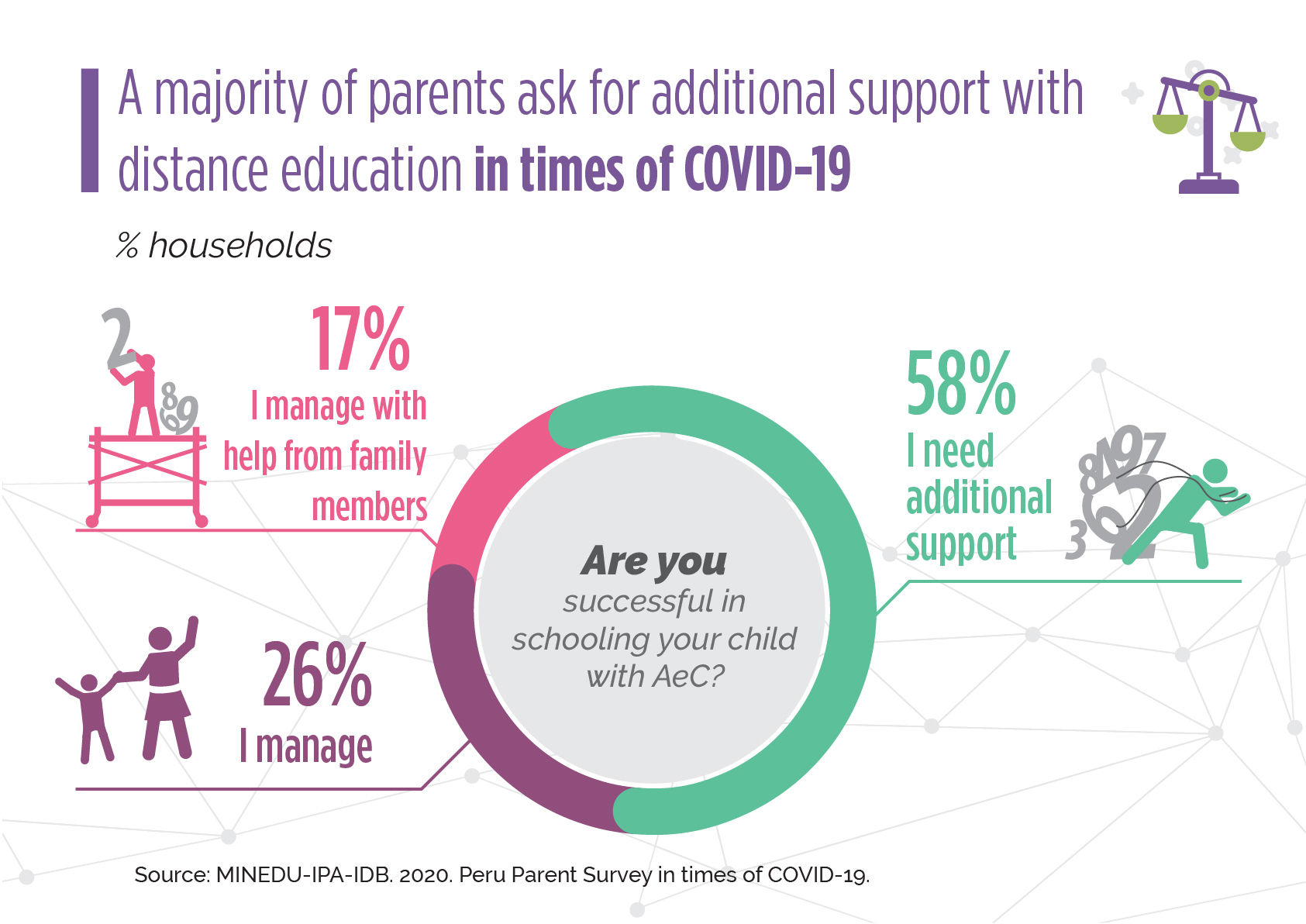

How do families suggest improving distance education during the pandemic? Nearly two-thirds of caregivers are asking for more support to improve learning at home, including guidance, resources, and materials.

The data presented above is part of a monitoring and AeC evaluation strategy to learn about what works in distance education. In the posts to come, we will share more findings from the perspectives of families, directors, and teachers on education in the time of COVID-19. The digital divide has been a significant barrier in dealing with the pandemic, as many students in Latin America and the Caribbean cannot use the internet at home and are disadvantaged in accessing remote learning, also losing the opportunity to access complementary resources that could strengthen their learning. The results from Peru teach us that one size does not fit all. A multifaceted distance education program like AeC offers opportunities for more students to continue their learning.

In the weeks to come, we will share more on the IPA blog about findings from our COVID-19 research with Peru’s Ministry of Education.

We thank the following people for their contributions to the project: Victoria Garcia-Blázquez Vigo, Vladimir Castro, Clarisa Yerovi, Luciana Velarde, Claudia Paola Lisboa Vásquez and Nicolás Besich (OSEE, Minedu); Juan M. Hernández-Agramonte, Olga Namen, Kelly Montaño, Rayssa Ruiz and Joaquín Armas (IPA); Emma Näslund-Hadley and Carolina Méndez (IDB).