Five Lessons From a Year of Sharing Evidence Strategically

A long-time supporter of IPA recently gave me the gift of a very open-ended question—something along the lines of “So, how did things go this year?” As we close a very eventful 2019, it was refreshing to be able to recollect some highlights of IPA’s policy engagement around the world and reflect on what we’ve learned and where we’re going next on the second pillar of our strategic ambition: sharing evidence strategically.

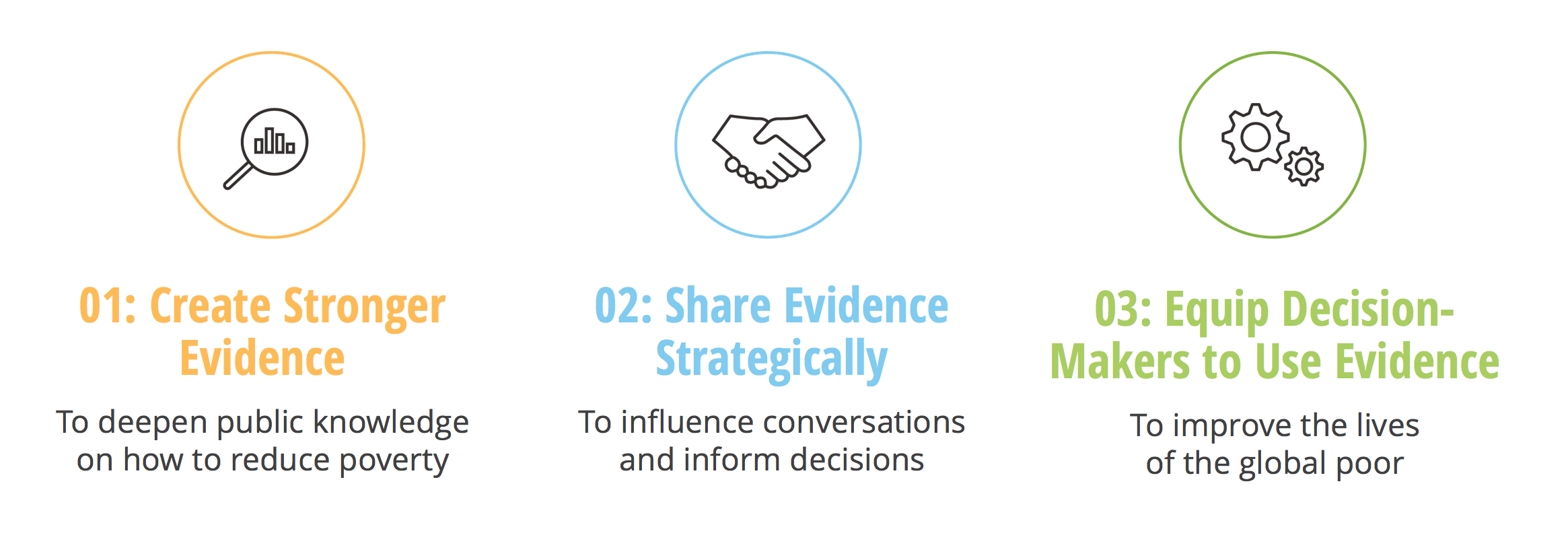

(Since it’s just possible that you don’t have IPA’s strategic plan memorized as I do, I’ll just link you to Annie Duflo’s great post from last year, explaining how we are thinking about our work in three pillars, also pictured below).

My small glimpses of how this is going are simply snapshots of the kind of long-term engagement our teams are doing daily in their contexts to ensure that evidence is relevant, credible, and ultimately used. Perhaps that is the key lesson: that evidence-based change requires long-term commitment to making yourself (and the data) useful to the ultimate users of evidence.

Evidence-based change requires long-term commitment to making yourself (and the data) useful to the ultimate users of evidence.

1. Be prepared for the policy window: embedding data support in Rwanda

This year, results from Rwanda showed that structuring teachers’ contracts to peg increases to student performance resulted in better learning outcomes—and was popular with teachers. As results were coming out, Cabinet announced they were centralizing teacher management and recruitment— a critical system change and policy window that we realized could enable a large-scale, evidence-informed change in teacher contracts. Thanks to the longstanding relationships we’d built in the sector, we were requested to support the Teacher Development and Management Department (TDM) with this system change.

Now IPA Rwanda is working with researchers, the Rwandan Education Board (REB), and the International Growth Centre (IGC) to support TDM with the system changes and build a larger evidence-informed system. Sophie Mushimiyimana and Leo Mfura, research and policy staff from IPA, are working with REB to offer evidence-informed advice on teacher motivation strategies and centralizing teacher recruitment and deployment. The project sets the stage for the design of an evidence-based teacher placement algorithm that aims to improve the matching of teachers to suitable schools and ultimately for engaging the whole sector with more evidence-informed decision-making.

A classroom from a school included in the evaluation.

2. Be patient and stick to your guns even amidst controversy: Improving education in Liberia

In 2016, Liberia embarked on an ambitious and controversial plan to assess whether private school operators could effectively run public schools. As you can imagine (or may know well), the politics around this study have been anything but simple from the beginning. Luckily, this study has had the leadership of brilliant, committed researchers—Mauricio Romero (ITAM), Justin Sandefur (Center for Global Development), and Wayne Sandholtz (UC San Diego)—as well as a team of dedicated Liberian research staff, currently led by Dack Dolo, and government partners and private operators who cooperated with (and certain ones who helped to advocate for) a rigorous independent evaluation.

As you’ll see from the online conversations, the team and everyone associated with it has been bombarded by criticism from all sides from the very beginning, including by various threats to their reputations. But being patient, striving to rise above the controversy, and consistently aiming to be clear and neutral in sharing the results (and only the results) has paid off in terms of influencing both the conversation and the decisions around this program.

As we spoke with the Ministry, we realized that these results were indeed having an influence on decisions.

Liberia’s government changed in 2018, resulting in a newly staffed Ministry of Education mid-study. In July of this year, before the controversy swelled up again, we all sat down with members of the current administration, including the Minister of Education and the Deputy Minister of Research and Planning, for a few hours to pore over the preliminary endline results and hear their feedback. As we spoke with them, we realized that these results were indeed having an influence on decisions. For example, one of the clearest things that emerged through the midline results (available in brief and full paper form) which we had presented to the Cabinet in 2017 (before the change in government), was that variation in contracting had allowed one operator to cut school size, sending the excess kids back into the public system. Having seen this, the Ministry tightened the rules of the contracts for the coming year to make for a more realistic and sustainable program.

Just this week, we released endline results from the project (brief and full paper). Since results were just released, it’s still too soon to see exactly how they will influence the program’s future—but the Minister and the international community at large are clearly paying attention, and we hope that they all take note of the variation between providers and the overall nuanced results on outsourcing schools in Liberia.

3. Take a sectoral approach: advancing evidence-informed policies in Ghana

Stakeholders from Ghana's education sector gather annually at the Ghana Eduation Evidence Summit.

The Ghana Education Evidence Summit in August was a highlight of the year (as indeed it has been for the past two years). Ghana’s Ministry of Education co-hosts this annual event with several of its partners, including IPA, and it has become a high-quality forum to showcase the co-creation of evidence in Ghana and to encourage the use of evidence in education policymaking. This year, IPA started the summit with one very general goal—to support the Ministry of Education in integrating rigorous evidence into its annual sector planning—as well as three specific ones:

- Inform the Ministry of Education’s new kindergarten policy with the best evidence about early childhood education in Ghana

- Encourage further discussion on scaling up targeted instruction (teaching to the level of the child, a pedagogy shown to improve learning), particularly in anticipation of the World Bank’s plans to invest in Ghanaian education in 2019-2024; and

- Encourage data integration and use in education policymaking, especially as we found ourselves in the midst of several overlapping conversations around dashboarding, information systems, and the link to evidence-informed decision-making.

Ghana’s education sector indeed made progress on all three of these goals—through the Summit, but of course also through hard work before and after the actual event. Multiple Ministry partners are convening around the new kindergarten policy to make it evidence-informed and costed realistically—and to include a strong monitoring and learning component—so they can use data to measure and adjust as they go. The Project Appraisal Document for the GALOP project displays a commitment to following the results of the evidence on targeted instruction in Ghana (first study, second study). And while the conversation around data is ever-evolving, we were happy to conclude the summit with a call for more coordination, some featured stories of progress on data integration and coordination, and a vision for more of this in the future.

4. The only thing that is certain is change: Weathering political transition in Mexico

A constant challenge partnering with governments on research projects is that transitions are very common. Whether political transitions result from elections, an administration’s reshuffling of its appointees, or any number of other causes, they can throw a wrench in researchers’ best-laid plans. This has been especially true for IPA Mexico, where elections and government staff turnover alike have occurred at both the national and local levels in the midst of a series of research activities on policing led by researchers Rodrigo Canales and Mushfiq Mobarak (both from Yale University) and IPA in close cooperation with government agencies.

In Mexico, the research team has been able to continue its projects as the new government arrived. Some things are non-negotiable—namely, the rigor, relevance, and impartiality of the research itself—but within these bounds, we have found success in being responsive to changing priorities from our partners. In fact, as work winds down on the original two streams of work, we’re are now embarking on two new studies informed by the new government’s priorities. Earlier this year, we published a blog post sharing a few strategies IPA Mexico has found effective for maintaining and furthering our relationships with policy partners during turbulent times.

Some things are non-negotiable—namely, the rigor, relevance, and impartiality of the research itself—but within these bounds, we have found success in being responsive to changing priorities from our partners.

5. We might be data nerds, but human connection still matters for encouraging action: moving narratives in Bangladesh

IPA just launched a new Forced Displacement initiative, and one of the driving factors of that has been the great need for data and evidence on what works for forcibly displaced people. Indeed, the international community is hungry for it—too often the politics of host communities have been driving the narratives around what is best for both displaced populations, like the Rohingya, and host communities, like in Cox’s Bazar.

IPA has been working with the leadership of researchers C. Austin Davis (American University), Paula López-Peña (Yale), and Mushfiq Mobarak (Yale) to track refugees with a representative survey of more than 5,000 households, equally divided between Rohingya refugees and Bangladeshi host communities. The survey is a deep collaboration between several organizations, housed in a partnership of Yale's MacMillan Center and IPA with additional financial support from the Gender & Adolescence: Global Evidence (GAGE) program, the Poverty and Equity Global Practice of the World Bank, and the State and Peacebuilding Fund (SPF) administered by the World Bank.

The moment that really stuck out to everyone was when Mushfiq, a Bangladeshi researcher based at Yale University, stood up and reminded the mostly Bangladeshi room that what happened to this population was having the bad luck of being born on the wrong side of a river.

In Bangladesh earlier this month, IPA co-hosted an event with IGC to launch the findings of the survey’s first wave. The researchers demonstrated that the Rohingya were not all that different than the Bangladeshis living in Cox’s Bazar before they were displaced. They had similar assets such as homes, poultry, and cell phones, and worked in similar agricultural activities where they were just as productive.

But the moment that really stuck out to everyone was when Mushfiq, a Bangladeshi researcher based at Yale University, stood up and reminded the mostly Bangladeshi room that what happened to this population was having the bad luck of being born on the wrong side of a river—the data show that the Rohingya are not that different from us, he emphasized, and we need to ask ourselves how we should respond in that light. In doing this, Mushfiq used data to illustrate the human connection that exists between these communities—while this hasn’t completely changed the conversation yet, the Bangladeshi media certainly picked up on the facts, and we can start to see how a narrative might move from fear of the unknown to something more fact-based.

Mushfiq Mobarak presents results from the Cox's Bazar Panel Survey in Bangladesh.

IPA just turned seventeen years old, and we keep evolving as an organization to improve lives through advancing what works. Our first hurdle was just building an organization that could gather and use data effectively, but that’s not enough—we have to work hard to get it used. In sum, 2019 has been a year of sharing evidence strategically, to engage, inform, and equip our partners in the policy space. In turn, we too have learned a lot about how to ensure our mission is achieved—and I’m thankful for these hopeful glimpses into policy- and decision-making informed by better evidence.