Citizen Security and Policing Amidst COVID-19 in Mexico

By Rodrigo Canales, Julia Madrazo, and Jessica Zarkin

The COVID-19 pandemic has set in motion a series of crises that have not only presented enormous challenges for all governments but also have exposed and exacerbated pre-existing inequalities and fault lines. In few areas has this been more evident than in the relationship between police forces and the citizens they serve. And Mexico is no exception. There is a long and troubled history in the relationship between law enforcement agencies and the Mexican public. This has been further complicated by the onset of COVID-19, which has altered many aspects of crime and governance.

In Mexico City, for example, some of our work has shown that training police officers in procedural justice—to ensure that the people they interact with perceive interactions as fair and legitimate—was effective at changing officer attitudes and behavior. But rebuilding citizen trust takes time, effort, and consistency—especially given generalized perceptions of high crime and low police trustworthiness. What was already an uphill battle has been further complicated by the onset of COVID-19, which has changed police work and has added new tasks and potentially contentious interactions with citizens (e.g. assisting with public health efforts or enforcing government mandates).

To examine how COVID-19 has affected citizen perceptions and the challenges faced by the police, we conducted two complementary studies. The first, focused on public perceptions, was part of our 10-country RECOVR survey measuring a number of COVID-affected outcomes. Specifically, between June 5 and 29, we surveyed 1,330 people in Mexico City. The second was an extension of ongoing research, led by Rodrigo Canales of the Yale School of Management, studying how to build effective, resilient, and trusted police organizations in Mexico. For seven weeks, beginning in May, we carried out interviews with representatives of a broader sample of Mexican police forces, totaling 112 departments in 31 of the 32 Mexican states.

The gap between citizen and police perceptions during COVID-19

The data validate past concerns on police-citizen relations—55 percent of respondents reported having very little or no trust at all in the police. Only 7 percent responded that they had a lot of trust in the police. Fifty-one percent stated that police work during a pandemic was not very or not at all essential.

In contrast, 73 percent of police forces reported expanding their roles to activities deemed essential by local governments for COVID-19 mitigation. These included distributing public health announcements, assisting with health screenings in public places, and surveilling places like supermarkets to inform citizens and control altercations. But they also included more contentious activities that introduced new tensions and frictions, such as the enforcement of decrees and lockdowns, or restricting attendees at a funeral. As a result, several departments reported increased stress in relationships with the public, including more insults and hostility from the community. Others admitted that officers had become less tolerant of people’s non-compliance with health measures.

Yet, some departments found opportunities within this complex landscape. They anticipated upcoming problems, innovated, conducted officer sensitivity and empathy training, and established new mechanisms to connect with neighbors. One department, for example, recruited young volunteers to help monitor public compliance with health measures and avoid entangling its police officers.

Police as a vulnerable population

Police officers are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, not only because the nature of their work is more likely to expose them to the virus, but also because, on average, 13 to 20 percent of the staff in the interviewed departments were part of an at-risk population.1 Almost 70 percent of the departments had sent the vulnerable staff home, leaving the remaining force to absorb the additional work. And by early June, almost half of the departments we interviewed had staff with COVID-19, though only 43 of the 112 had actually tested their officers. Citizens seemed sensitive to this: 66 percent of respondents in the Mexico City survey acknowledged that the police had a heightened risk of exposure.

Police work is changing, but people don’t know it

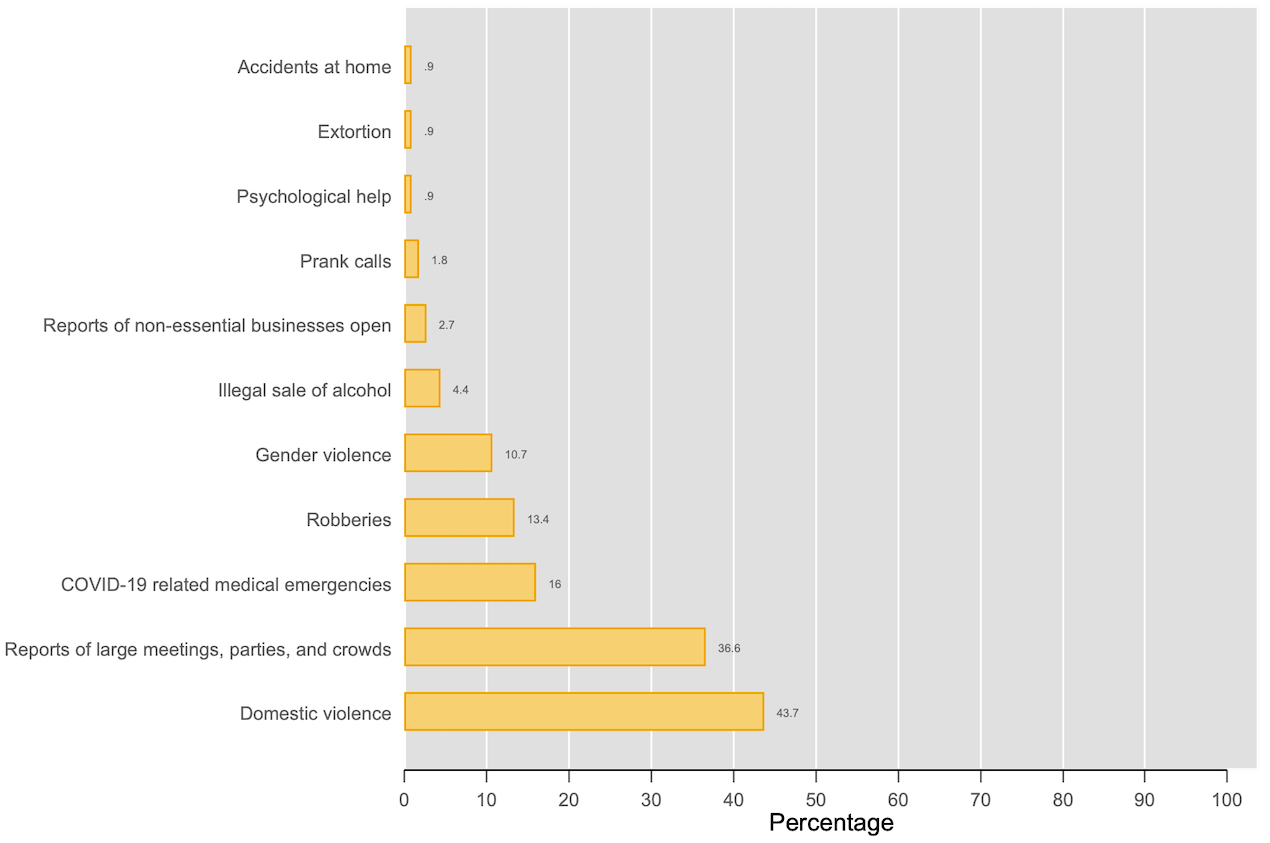

We compared what people thought about crime and security to data from police (with the important caveat that public perceptions were only measured in the Mexico City area). The people were split—at 45 percent each—on whether crime had increased or not in their neighborhoods since the start of the pandemic, with robberies and violent robberies being at the top of their concerns. In contrast, police departments reported both a change in crime dynamics and an increase in emergency calls that were not consistent with public perceptions. As shown in the graph, by far the biggest category that saw increases in reports was domestic violence, followed by reports of large group gatherings, then COVID-19 emergencies.

These data highlight that, when a crisis happens, police forces are typically in the first line of response. In the context of an already stressed relationship between the police and the public, the police must take on new roles, blurring the boundaries between public health and law enforcement while dealing with the pandemic inside their own departments. But this is not obvious to an already-skeptic public, for whom the evolution of policing is far from evident.

Building strong public safety requires a true partnership between police forces and the citizens they serve. This will only happen if each side begins to understand the other better, and we hope this ongoing research agenda can help inform that process. And crises present challenges but also opportunities, as demonstrated by the departments in our sample that innovated through the pandemic to establish new mechanisms to engage with the public, support neighbors, and increase citizen trust.

1. We considered vulnerable populations as: the elderly, pregnant women, tobacco smokers, and those with preexisting conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, or obesity.