Tracking Colombians’ Experiences with COVID-19: Households Face Mounting Challenges as Virus Endures

As Colombia continues to battle the coronavirus pandemic, it must—like many countries—address the twin concerns of protecting its population’s health and reactivating its hard-hit economy. The success of the government’s economic policies necessitates an understanding of how Colombians have fared in recent months and what challenges they continue to face. To support policymakers with timely data on the impacts of COVID-19 on Colombians’ livelihoods, IPA partnered with Colombia’s National Planning Department (DNP) and UNICEF to conduct the RECOVR survey1 on May 8-15 (Round 1) and August 13-22 (Round 2).

We assessed more than 1,0002 households’ experiences with a range of health, education, and economic issues over the phone. While the findings of the survey reveal a picture of acute economic impact, particularly for women, those who work in the informal economy, and who live in rural areas, there are also pockets of progress thanks to timely and well-targeted social assistance programs. In this blog post, we take a deeper look into the survey’s findings on social protection and family welfare, and how these takeaways can inform an inclusive and sustainable economic recovery in Colombia through evidence-based policies. You can access full results of the surveys on the Colombia homepage for RECOVR.

Colombia’s Public Health and Economic Policies

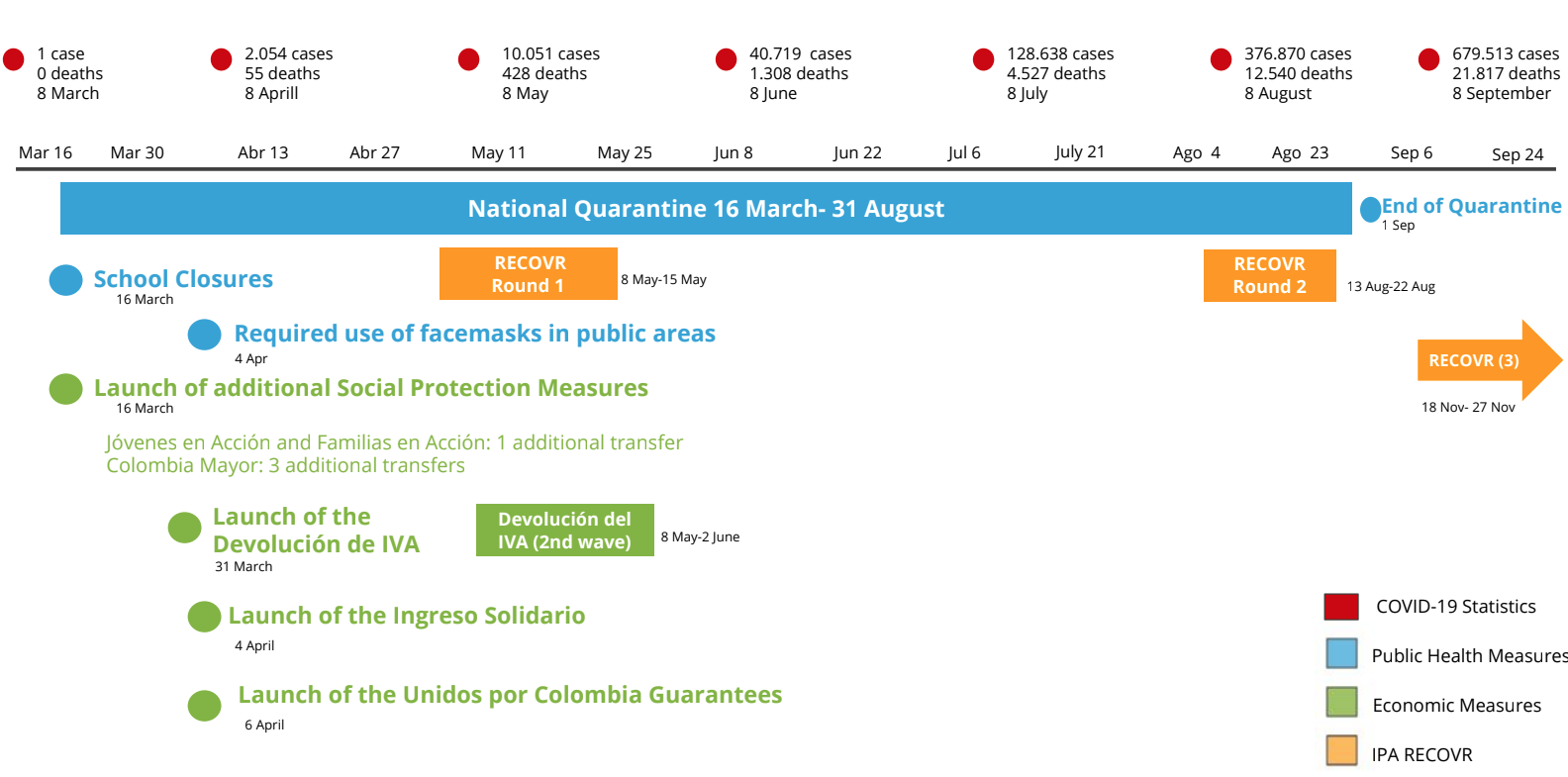

The graphic above outlines the trajectory of the pandemic in Colombia and public health measures enacted by the government, notably a national lockdown from March 22-August 31. Beginning on September 1st, the country lifted its quarantine and transitioned to maintaining preventative protective measures (e.g. face masks required in public areas, social distancing, and other strategies), while gradually allowing domestic travel and managing a safe economic reopening in tandem with the continued public health emergency. Continued case increases,3 however, pose a challenge to a full-fledged recovery.

The government took swift, decisive actions to support its most vulnerable citizens by launching a series of additional social protection measures and emergency cash transfers through the pre-existing Colombia Mayor, Jóvenes en Acción, and Más Familias en Acción and new Ingreso Solidario, Devolución del IVA, programs. Prior to the pandemic, Colombia’s social protection schemes covered 2.8 million families, 1.7 million low-income elderly, and 296,000 vulnerable youth. The social protection response to COVID has been comprised of a multi-pronged approach, and has thus far resulted in coverage for an additional 2.6 million vulnerable families (including informal workers):

- a series of extraordinary payments through the existing Colombia Mayor (COP 80,000/US$20/recipient), Más Familias en Acción (COP145,000/US $37/household), and Jóvenes en Acción (COP356,000/US$91/recipient),

- an accelerated timeline and expanded targeting of the Devolución del IVA to 1 million households that are recipients of cash transfer programs (COP78,454/US$20/recipient), and

- the unconditional Ingreso Solidario cash transfer targeting 3 million vulnerable households not registered for other social assistance programs (total COP480,000/US$130/household).

In addition, the government launched special financing and loan programs for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises through the Unidos por Colombia program. Encouragingly, such relief programs have also accelerated the country’s financial inclusion goals, with over 1.6 million adults opening a credit or savings account for the first time in the first six months of 2020, and another 2.3 million using financial services that had been inactive in December 2019.

Nevertheless, the crisis has had deep impacts in Colombia: unemployment levels persisted at 16.8 percent in August 2020 (a year-on-year increase of 6 percentage points), and a recent report by Universidad de los Andes warns that Colombia could lose two decades of progress in its fight against poverty. Existing cleavages in the labor market between the formal and informal economy have been further exacerbated, as have gender differences. In June, the OECD projected a GDP contraction between 6.1 and 7.9 percent for 2020, depending on the course the virus takes.

As Colombia looks to reactivate its economy, it will be critical to continue to provide timely, well-targeted, and evidence-based responses to the households and sectors most acutely affected by the pandemic.

Inequalities Have Been Exacerbated by COVID-19, Driving Home the Need for Continued Social Protection Measures

The RECOVR results demonstrate how the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the scale and extent of economic vulnerability in the country, and the challenges policymakers will need to address. When analyzing the two survey rounds, we see the following trends:

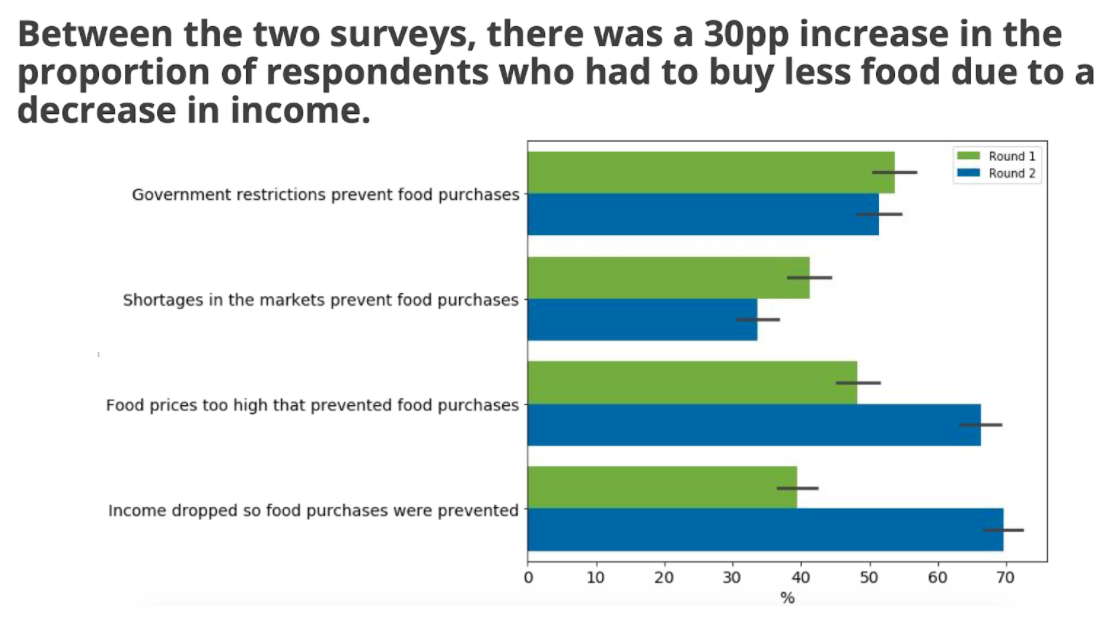

Over time, more respondents report being food insecure on many measures. Between the two survey rounds, there was a 30 percentage point (pp) increase in the proportion of respondents who had to reduce food expenditures due to a decrease in income, with greater impacts among more vulnerable populations. The rate of adults with informal employment who reported having to reduce their portions or cut back on at least one meal exceeded the rate of adults with formal employment needing to do so by nearly 20 pp.

Parsing the data further, we see that respondents in rural areas are more affected by market shortages, and adults in Strata 14 reduced their portions and number of meals more often. In addition, households that were unemployed before and during quarantine are more likely to reduce their children’s meal portions and number of meals than those who kept their jobs.

Employment and economic activity have suffered significantly, with women and those with informal employment reporting larger losses and slower recovery. While male respondents have fully recovered their employment levels between February and August, a 5.6 percentage point employment gap remained among female respondents’.5 In the second survey round, 80 percent of respondents with formal employment indicated that their workplace was operating, less than 65 percent of respondents who were informal employees had operating workplaces.

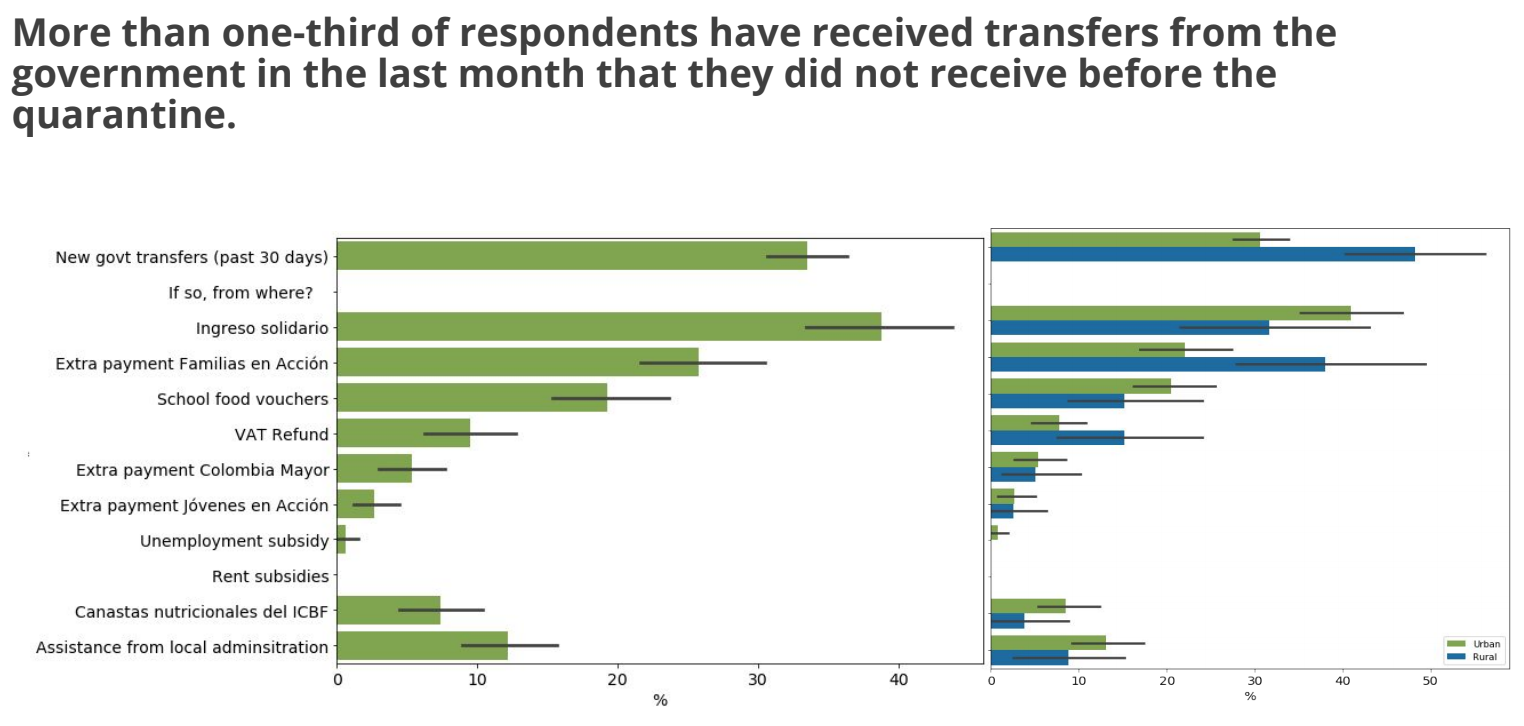

Households that report increased take-up of social protection programs reported less food insecurity. In the second round, more than one third of respondents reported receiving transfers from the government in the last month that they did not receive before the quarantine. Nearly half of rural respondents and nearly one third of urban respondents reported receiving a new government transfer. Households that received additional government transfers during the pandemic were less likely to report reducing food portions and the number of meals for children in the household. In addition, about 52 percent of respondents reported benefitting from at least one financial relief program in recent months.

Households are making difficult choices to meet their basic needs. Nearly one-third of respondents reported using savings to pay for food, health care, or other expenses since mid-May. About 64 percent of respondents reported that their debts had increased during the quarantine period, though respondents with formal employment were better able to avoid taking on debt.

How Are Families Faring?

Lockdowns, remote education, isolation, and other protective measures, though critical to control the virus, can lead to strains on mental health. The second round of RECOVR included a module on family welfare to understand how families and children are coping with the pandemic, how they are spending their time, and whether they have increased concerns of violence, to inform our partners’ programming responses.

Children face new worries and responsibilities. More than 40 percent of children (6-18 year-olds) have developed additional anxiety or mental health concerns since the onset of quarantine, though nearly one third also reported not being affected by the current situation. Children may also be called upon to contribute to the household. Apart from time dedicated to education and leisure, 42 percent of children in the surveyed households spend most of their time on work activities, particularly domestic ones. While we do not have comparison data to see what percentage of children were contributing to household work before the survey, this is nevertheless a sizable portion of the sample.

Domestic violence is a concern. Nearly 20 percent of respondents indicate that the most frequent arguments in the home are between the couple living there, but more than one third indicate no major arguments. In addition, seven percent of respondents who live with a partner report being more concerned about physical violence between partners since the beginning of quarantine. While any increase in domestic violence is cause for concern, this proportion allows policymakers and community organizations to prioritize preventive approaches and early warning systems.

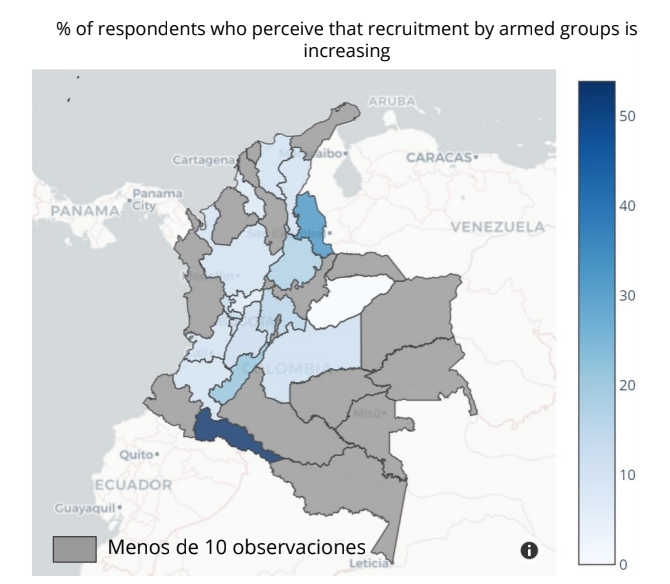

Recruitment of adolescents and children into organized criminal organizations may be increasing, and we found no evidence of criminal groups enforcing quarantine measures. Fifteen percent of respondents in households with children ages 6-18 perceive that during quarantine the recruitment of children/adolescents by armed groups/BACRIM (bandas criminales, or criminal bands) in their community has increased, particularly in Putumayo and Norte de Santander, which have been traditional strongholds for high levels of coca cultivation that have increased in recent years. A different ongoing study on gang governance found that the sensationalized headlines from early in the pandemic about gangs enforcing quarantine do not hold up in Medellin, where a survey of all low- and middle-income neighborhoods showed the government, not organized criminal groups, was providing most public health and social services, except for in a few neighborhoods.

Looking Forward: Answering Policy Questions with Evidence

The two RECOVR survey rounds lay out both the acute negative effects of the pandemic on Colombians’ livelihoods and well-being as well as the usefulness of emergency measures to prevent the already poor from falling into destitution. We find that while the population on average has felt the brunt of the slowing economy, those who have received government aid have been protected to some extent. As the Colombian government has already spent COP$3.8 trillion (US$1 billion) on social transfer programs alone, it is not immediately evident how long emergency economic aid can be extended as the crisis lingers (as of now, Colombia Mayor, Familias en Accion, and Jovenes en Accion extraordinary payments have been extended through December). Finally, promising news about vaccine developments offers cautious optimism about the conclusion of the pandemic, but it may take months, if not years, to deliver vaccines across middle and lower income countries. Apart from the logistical and monetary challenges of vaccine distribution, questions also remain in many countries regarding public trust and propensity to receive a vaccine in the first place. Encouragingly, 80 percent of Colombian RECOVR respondents indicated that they would receive a vaccine, which the government can build on when developing implementation strategies.

As we highlighted in a previous post, we are working to develop rigorous evidence on what policies and programs provide cost-effective responses. We are currently partnering with DNP to evaluate the impact of expanded social protection measures for vulnerable Colombian households, with Mercy Corps to evaluate the impact of a cash assistance program to vulnerable migrants ineligible for government transfers, and with the Colombian Institute for Family Welfare (ICBF) to evaluate the impact of an informational campaign designed to provide parents and caregivers with the knowledge and skills to support to their children’s learning process at home. Results are forthcoming, but you can read about these projects and many more on IPA Colombia’s website and the RECOVR Research Hub.

Finally, we look forward to sharing insights from the third round of the RECOVR survey, implemented in November, in early 2021.

1. Tracking how people’s lives are affected by the COVID-19 pandemic can enable policymakers to better understand the situation in their countries and make data-driven policy decisions. To respond to this need, IPA has developed the RECOVR survey—a panel survey that facilitates comparisons, documents real-time trends of policy concern, and informs decision-makers about the communities that are hardest-hit by the economic toll of the pandemic. More information is available at https://www.poverty-action.org/recovr/recovr-survey.

2. The panel survey was conducted in two rounds in May and August (with a third round set for November) and reached 1,508 respondents in the first round and 1,013 in the second through Random Digit Dialing. This method generates the cell phone sample from a database of all possible cell numbers based on Colombia’s cell numbering plan. All possible combinations of mobile telephone numbers are included, ensuring equal probability of selection. We engaged Sample Solutions, a firm that pre-pulses randomly generated possible numbers to identify numbers that are in use, to provide us with a random sample to attempt via RDD. Sample Solutions provided us with a sample that was proportionate to mobile network operator market share, since the subscriber composition of different carriers may vary in important ways.

3. By October 24, Colombia surpassed 1 million cumulative cases since the start of the pandemic.

4. Strata are socioeconomic designations utilized by the National Administrative Department of Statistics ( DANE—Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística). https://www.dane.gov.co/files/geoestadistica/Preguntas_frecuentes_estratificacion.pdf. Strata 1-3 are the lowest socioeconomic strata levels and correspond to those receiving utility services subsidies. Strata 4 does not receive any subsidy and does not have to pay extra for subsidizing the lower stratos. Strata 5 and 6 have to contribute for the utility subsidies of the lowest stratas.

5. Question inc7 asked whether respondents worked at least one hour in the last 7 days. Female respondents reported as follows: 51.9% worked in February, 41% worked in May, 46.3% worked in August.